Newman's Road to Rome

- PAT MCNAMARA

What made the conversion of John Henry Newman so especially noteworthy, and what did it cost him to cross the Tiber?

|

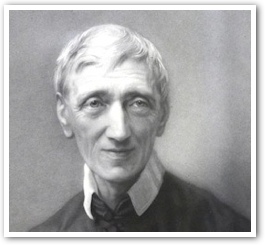

Blessed John Henry Cardinal Newman

1801-1890 |

Because he was one of the leading religious thinkers of the 19th century, Cardinal John Henry Newman's beatification by Pope Benedict XVI in October 2010 was a long awaited event for Catholics and non-Catholics alike. A poet, theologian, novelist, apologist, and pastor, as a convert he authored one of the greatest spiritual autobiographies in English, Apologia Pro Vita Sua (1864).

Born to a Protestant middle-class English family on February 21, 1801, he was the oldest of six children. A gifted student, he entered Oxford at only 15 years of age. Newman briefly considered a secular career, but chose the ministry instead. Ordained at 23, he served in a parish before being appointed a Tutor at Oxford's Oriel College, which provided a comfortable living in a fairly congenial academic setting. The future looked bright for Newman.

Soon thereafter, Newman was appointed Vicar of St. Mary's, Oxford's university church. There he achieved a reputation as one of the day's foremost preachers. A contemporary recalled one sermon:

Newman had described closely some incidents of our Lord's passion; he then paused. For a few moments there was a breathless silence. Then in a low, clear voice, of which the faintest vibration was audible in the farthest corner of St. Mary's, he said, "Now I bid you recollect that He to whom these things were done was Almighty God." It was as if an electric stroke had gone through the church.

As for his educational work, he considered this pastoral ministry. Through his writings he was becoming an authority on early Church history. Tall but slightly stooped, at five foot nine, Newman may have not have made an impressive figure, but he did make an impression on people, especially the young. One Oxford graduate recalled:

In Oriel Lane light-hearted graduates would drop their voices and whisper, "There's Newman," as with head thrust forward and gaze fixed as though at some vision seen only by himself, with swift, noiseless step he glided by. Awe fell on them for a moment almost as if it had been some apparition that had passed.

As increased government control threatened the Anglican Church's prophetic role, Newman led a movement to reclaim it, known as the Oxford Movement. The Church, he believed, had "a Divine appointment" independent of the state "with rights, prerogatives, and powers of its own." A major concern was that Bishops were being appointed for political rather than religious orthodoxy. The Church wasn't worth much, Newman wrote, "if she is to be nice and mealy-mouthed when a piece of work is to be done for her good lord the State."

For members of the Oxford Movement, the Church of England was a middle way (Via Media) between Puritanism, which discarded ancient traditions, and Roman Catholicism, which corrupted them. Only the Anglican Church was truly Catholic, in the sense of universally applicable. As they reexamined Marian devotion, the roots of the liturgy, and the sacrament of confession, some felt they were veering too close to Rome. In fact a growing number, many of them Newman's friends and students, did convert.

Little by little, Newman's objections to Roman Catholicism were breaking down under extended examination. "Catholicism," he would later write, "is a deep matter — you cannot take it up in a teacup." |

Newman himself was raised to believe that Rome was the Antichrist predicted in scripture, but he also opposed "ultra-protestantism," which discarded everything Roman. His own reading and study was leading him to a different direction than originally intended. To justify the Via Media position, he had gone back to early Church history.

Little by little, Newman's objections to Roman Catholicism were breaking down under extended examination. "Catholicism," he would later write, "is a deep matter — you cannot take it up in a teacup." He was coming to see it, rather than his own Church, as the true successor to the Apostles. There was nothing, he insisted, "which the Church has defined or shall define but what an Apostle, if asked, would have been fully able to answer." As his objections disappeared, he moved closer to converting.

On October 9, 1845, at age 44, John Henry Newman was finally received into the Roman Catholic Church. His Anglican life was ended. "I am going to those whom I do not know," he wrote, "and of whom I expect very little — I am making myself an outcast, and that at my age." It was a sacrifice in which he felt "no pleasure."

Newman's conversion shocked many, both Catholic and Protestant. For a clergyman to do so meant starting completely over, giving up a comfortable position. For many converts, it involved the loss of lifelong friends, even ostracism from family. (Anti-Catholicism was still a powerful element in 19th-century England.) Newman found many lifelong relationships abruptly ended.

The reason Newman converted, he wrote, was that "I consider the Roman Catholic Communion the Church of the Apostles." For Newman, Roman Catholicism didn't just claim to offer the truth; it was the Truth. He had dedicated his whole life to the pursuit of truth, wherever it might lead. This was the theme of his greatest poem, "The Pillar of the Cloud," written in 1833:

Lead, kindly Light, amid th'encircling gloom, lead Thou me on!

The night is dark, and I am far from home; lead Thou me on!

Keep Thou my feet; I do not ask to see

The distant scene; one step enough for me.

I was not ever thus, nor prayed that Thou shouldst lead me on;

I loved to choose and see my path; but now lead Thou me on!

I loved the garish day, and, spite of fears,

Pride ruled my will. Remember not past years!

So long Thy power hath blest me, sure it still will lead me on.

O'er moor and fen, o'er crag and torrent, till the night is gone,

And with the morn those angel faces smile, which I

Have loved long since, and lost awhile!

Change is never an easy thing, but for Newman it was an essential component of authentic personal growth. "In a perfect world it may be otherwise," he wrote. "But here below to grow is to change, and to be perfect means to have changed often."

As a newly minted Roman Catholic, John Henry Newman had no immediate prospects before him. Catholicism was unfamiliar terrain. Attending his first Masses, he didn't completely understand them, but a belief in Christ's Eucharistic presence sustained him:

[A]fter tasting of the awful delight of worshipping God in His Temple, how unspeakable cold is the idea a Temple without that Divine Presence! One is tempted to say "What is the meaning, what is the use of it?" It was that 'Great Presence' which made a Catholic church different from every other church in the world.

|

He wanted to continue in ministry, within a religious community. In the Oratorians he found a happy balance between community life and individual initiative, between scholarship and pastoral work. Founded in 16th-century Italy by St. Philip Neri, members lived in communities known as Oratories, literally "houses of prayer."

As a priest, Newman opted to work with the poor, "in the midst of the mechanics." He chose Birmingham, a large industrial town, to start an Oratory. He stayed there for the rest of his life, lecturing, writing, and doing parish work. Although Newman wrote prodigiously, he didn't live in an ivory tower.

His Idea of a University (1851), a series of lectures on higher education, is still a standard in the field. The Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845), written just before his conversion, shows the Church as a living, growing body, rather than a static institution. His published lectures and sermons are still in print. An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent (1870) laid out a framework for religious belief.

His early years as a Catholic weren't easy. While former colleagues called him a traitor, many Catholics considered him a closet Protestant. During the 1850s, an ex-priest whose misdeeds he had chronicled sued him for libel in a highly publicized case, and won. Newman was named to head an Irish Catholic university that never got off the ground. As editor of The Rambler, an independent Catholic journal, he advocated the role of the laity, which got him in trouble with conservative bishops.

At one point Newman wrote, "O how forlorn and dreary has been my life ever since I have been a Catholic!" At times it seemed "nothing but failure." He felt that his earlier Anglican writings "had far greater power, force, meaning, success, than my Catholic works — and this troubles me a great deal." At the same time, however, he felt he would be a "consummate fool" to "leave a land flowing with milk and honey" for "confusion."

"The Church is ever ailing ... Religion seems ever expiring, schisms dominant, the light of truth dim, its adherents scattered. The cause of Christ is ever in its last agony." |

When minister-author Charles Kingsley attacked him in print as a liar, Newman used the opportunity to defend his conversion, still a point of controversy after twenty years. His Apologia Pro Vita Sua ("Apology for His Life") traced his spiritual journey. It was quickly acknowledged as a classic in religious autobiography. The book did much to dispel anti-Catholic prejudice, for it showed that Catholics were human beings who cared for the truth too.

But Newman was still suspect among conservative Catholics. During the First Vatican Council (1869-1870), Pope Blessed Pius IX formally declared papal infallibility, a move intended to reassert his spiritual authority in a secularizing world. Newman was among those who considered the declaration "inopportune," further alienating the Church from the modern world. Although be ultimately supported the declaration, he operated under a cloud with his superiors.

An important characteristic of Newman's thought is balance between opposite extremes. Too conservative for liberals and too liberal for conservatives, he transcends both labels. While he spent his life fighting secularism and relativism, he also saw in certain Church quarters "a narrowness which is not of God":

Instead of aiming at being a world-wide power, we are shrinking into ourselves, narrowing the lines of communion, trembling at freedom of thought, and using the language of disarray and despair at the prospect before us, instead of, with the high spirit of the warrior, going out conquering and to conquer.

Pope Leo XIII (1878-1903) vindicated Newman when he named him a Cardinal in 1879, for his contributions to Catholic intellectual life. "The cloud is lifted from me forever," Newman wrote. The English people, Catholic and non-Catholic, hailed this move. Oxford invited him back, making him an honorary fellow of his old college. His last years were peaceful ones.

John Henry Newman died at 8:45 p.m., on Monday, August 11th, 1890. Today his writing is still included in English anthologies, and books continue to be written. A poet, letter writer, essayist, preacher, novelist, scholar, philosopher, and theologian, no other writer of his time had such versatility. His writings on freedom of conscience and the role of the laity, as well as his dynamic view of the Church, had a profound effect on the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), which addressed these topics in its proceedings.

As a Cardinal, Newman's motto was Cor Ad Cor Loquitur ("Heart speaks to heart"). Today he still speaks to a Church dealing with scandal. Regarding this issue, he wrote:

The whole course of Christianity from the first ... is but one series of troubles and disorders. Every century is like every other, and to those who live in it seems worse than all times before it. The Church is ever ailing ... Religion seems ever expiring, schisms dominant, the light of truth dim, its adherents scattered. The cause of Christ is ever in its last agony.

But the Church was like Noah's ark, "which did not hinder or destroy the flood but rode upon it, preserving the hopes of the human family within its fragile planks."

One bishop said of Newman, "There is a saint in that man!" Another contemporary called him "a being unlike anybody else." One visitor commented that a "light emanated from his person." A recent study labels Newman "a saintly scholar and a scholarly saint." But when called a saint, Newman replied that they "are not literary men." He would be content, he said, to polish the saints' shoes, if they used "blacking in heaven."

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Pat McNamara. "Newman's Road to Rome." Patheos (June 27 & July 4, 2011).

Reprinted with permission of Patheos.

Founded in 2008, Patheos.com is the premier online destination to engage in the global dialogue about religion and spirituality and to explore and experience the world's beliefs. Patheos is unlike any other online religious and spiritual site and is designed to serve as a resource for those looking to learn more about different belief systems, as well as participate in productive, moderated discussions on some of today's most talked about and debated topics..

The Author

Dr. Pat McNamara is a Professor of Church History at St. Joseph's Seminary, Dunwoodie. He blogs about American Catholic History at McNamara's Blog. McNamara's column, "In Ages Past," is published every Tuesday on the Catholic portal. Subscribe via email or RSS.

Copyright © 2012 Patheos