Grave, Where is Thy Sting?

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

With how great a cloud of witnesses are we surrounded! cries the author of the poetic Letter to the Hebrews.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

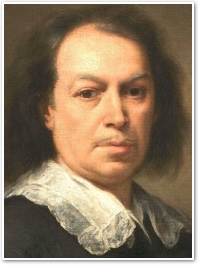

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo1617-1682

What painter ever touched his canvas with so vast an array of human faces, each distinct, himself and no other, and yet in each, old man and youth, maiden and grandmother, king and peasant, the countenance of the Lord Jesus shining forth! Such are the saints of God.

The scene is Seville, 1662. Two men are in conversation. I know only two places where men so opposed in character would be next to one another. One is a graveyard. The other is the Church. The older man is the painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. Beneath his serious bearing and solid build lies a soft and gentle soul. He came from a large, happy family, he studied art, and after a very little travel he settled down in his beloved home of Seville. For years he has been Spain's greatest painter of religious art. He can do nothing tragic, nothing harsh. Dante's Inferno is not in him. His realism is touched with kindness, so that when he paints beggars or street children, they may not be beautiful but they win us with their life and their spirit. No one ever painted the faces of children so well. When he turns to Scripture or the saints, there's a spark of delight in him, a kindness that ensures that whatever he does, it will not quite be like anything we have seen before. Look at his prodigal son. There's the father we expect, his arms flung wide and servants with fine robes for the boy to wear; but our eyes turn to a little white dog in the foreground, leaping for joy. If only we were all as faithful to God as our dogs are to us!

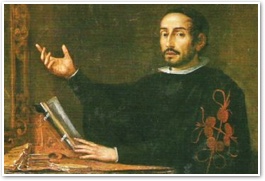

The other man is only thirty-five, but he has been through a hell of his own making. He is Miguel Mañara, known with horror and admiration as the living "Don Juan" of legend. He spent his youth, when not at war, seducing a thousand women and slaying their jealous husbands and angry fathers. Then he met Geronima, the only woman he ever loved, and took her as his wife, returning to Seville, whose people were not glad to have him back. But he had changed. It wasn't only that he settled down. He turned inward: he saw strange warning visions. When his wife died suddenly, he devoted the rest of his life to prayer and strenuous works of piety. He begged to become a member of the Brotherhood of Charity, founded to give a decent burial to executed criminals and the indigent. Only in the Church would we find such a thing; secular man knows nothing of such kindness.

The brotherhood admitted Mañara, and he soon became its mayor, its chief. Murillo was one of the brothers. Mañara wanted to expand the brotherhood's work; and Murillo would be a part of it: a killer redeemed, and a man of peace.

The Poor Deserve Our Best

"Senor Murillo," I imagine the younger man saying, his face handsome, though creased with dissipation and suffering, "I want us to do more than bury the dead. That's only one of the seven works of mercy. We might do the other six also."

Miguel Mañara

Miguel Mañara1627-1679

"As private persons, Mayor, many of us do these already."

"Yes, but the Hermandad is more. Come and see." And Mañara motions toward a window looking out over the streets of Seville.

For better and for worse, there was no state welfare department. The Church was the mother of the poor, and the hearts of her truest children were their shelter. The poor you will always have with you, said Jesus, and Seville proved it. Spain had suffered a bad year of the plague, and in its wake there were even more houseless people than usual, and more orphans on the streets.

Murillo looked down and saw three ragged boys in an alley. Their clothes were filthy. One of the boys was chewing a crust of bread, his shirt torn and falling about his chest. His dog sat beside him, hoping to get some. His companions sat sprawling on the cobblestones. The trousers of one boy were torn up to the knees, and the painter could see the soles of his shoes worn through. A broken jar and a basket of onions lay nearby.

The boys were playing dice.

"What do you have in mind, Mayor?"

"I want to turn the church of the Brotherhood into a hospital. And I want you, the greatest painter in Spain," said Mañara with a touch of his old suavity, "to grace it with six works of mercy. The seventh, you know, we already have." For behind the altar of their Church of the Holy Charity stood a Baroque masterpiece by Pedro Roldán, of the burial of Christ, a polychrome sculpture emerging from a painting of Calvary and framed, as if in a theater, by the gilt pillars and canopy of the architecture roundabout.

Our bodies were fashioned by God as fit tabernacles for his image and likeness, and even in death they are precious and to be treated reverently. The Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head, said Jesus, and that was true also on Good Friday, when our Lord had to be buried in a borrowed tomb, hewn out of rock for the rich and pious Joseph of Arimathea. To bury a poor man with honor is to repeat Joseph's loving deed.

"Our hospital," the Mayor continued, "will house the sick and the poor, and give them food and drink and clothing."

"What about the children, Mayor?" The game had broken up and the boys were scuffling, while the dog barked and the onions rolled here and there.

"The children we bring in, we will teach," said the Mayor.

The One Thing Needful

If you leave a child in a cold white institution to be fed and clothed by functionaries, but not loved, he will not thrive. Modern man is good at building cold white institutions: schools, hospitals, housing complexes, and hospices. We are not cheap with the poor, except in what people need most, which is love. Then we are as tight-fisted as Scrooge. But when the poor were cared for in the Hospital of Charity in Seville, they were granted many a grace, not least of which was the work of Murillo.

He gave the hospital eight paintings, according to Don Miguel's instructions. We are to visit prisoners, as the angel visited Saint Peter and released him from his chains. We are to house the homeless, as Saint John of God did, carrying the poor man on his back; that also applies to travelers, as Abraham welcomed the three young men and showered them with hospitality. We are to give drink to the thirsty, as Moses did when he struck the rock in the desert. We are to clothe the naked, as the loving father did when his scapegrace son returned from the far country. We are to tend to the sick, as Jesus healed the paralytic at the pool, and as Saint Elizabeth of Hungary did during the Black Death, caring for people whom no one else would approach. Murillo could never do anything macabre, so the focus in his painting of Saint Elizabeth is a basin over which the good queen has a small boy leaning, while she cleans his hair of lice; another boy in the background is scratching his head with one hand and his chest with the other. The whole is surmounted by a dome of deep blue, like sapphire.

So are seven of the paintings. Let's dwell a little on the eighth. We are to feed the hungry, as Jesus fed the crowds with the five loaves and two fishes. Murillo's treatment of the miracle is quiet and mysterious. The sky is darkening, and the crowds fade far into the background, hill after distant hill. In the foreground we see Jesus seated and the Apostles around him, a wicker basket at his feet. He is blessing the loaves. To the right of Jesus, almost in the center, stands a boy with two large fish in his arms. He is striding forward and looking up into the face of Saint Peter, to whom he is offering the fish. Feed them yourselves, Jesus had said to the Apostles, who did not know how they could do it, but this boy — may he enjoy a special glory in heaven — came forth with his basket of food.

That suggests another sense in which the poor need love. They are not our clients. They are our brothers and sisters, who need also to be able to shower their love upon us. The clasp of a hand goes both ways.

That was what the painter and the penitent gave to the poor of Seville. Four of Murillo's eight paintings still stand there; the others are copies, because modern man buries art in morgues for culture that are called "museums," so that if you are in Ottawa, Washington, Saint Petersburg, or London, you may see at great trouble what people who had not a coin in their pockets once saw to their comfort, as they looked up from their prayers.

And when they lay dying, they need not stare at the pocked white tiles of a drop ceiling, and listen to the cold alarm of a machine; they could look upon holiness, and they might hear, from the priest assisting them at their departure, the words of promise which draw the poison from sickness and the sting from death.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: "Grave, Where is Thy Sting?" Magnificat (April, 2017).

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: "Grave, Where is Thy Sting?" Magnificat (April, 2017).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2017 Magnificat