A Catholic to the Roots

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

No director felt more keenly the holiness of manhood and womanhood than John Ford.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

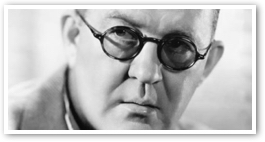

John Ford

John Ford1894-1973

The fiery redhead is looking down at her newlywed husband, who is planting roses in a garden in front of their cottage. She loves him passionately, as he loves her, but they've not yet shared the same bed. That's because she won't have him unless he fights her stubborn brother for her dowry. She does not know why he is unwilling to fight, and is ashamed for him. But he has left his native land and come to the "old country" of Ireland, in part to set his past as a prizefighter behind him. For a punch of his had killed a man in the ring, a "good egg," as he calls him, with a wife and a couple of kids. He has not told her about it.

"It was an accident," says the friendly vicar to whom Sean Thornton goes for advice.

"It was no accident," Thornton replies. "When I got into that ring, I could think only of beating his brains out. I wanted to kill him."

So there she stands, hands on hips. "What a foolish thing it is, to be planting roses when you should be planting potatoes!"

He glances up at her. "Or children," he says, and she falls silent.

Immigrant son

If you ever visit Portland, Maine, go to the intersection of Pleasant Street and York Street, where you'll find a bronze statue of a man sitting in a director's chair, smoking a pipe, a crumpled ten-gallon hat on his head for shade. The inscription beneath tells you that the man was born John Martin Feeney, and died John Ford — the greatest of all American movie directors. He was also a Roman Catholic through and through.

My students sometimes ask me whether great art in every genre is always with us, but we don't recognize it as great until many years later. I tell them that I don't think that's so, and that drama is the most sporadic of them all. For really great drama, I think you need something like the life and the world of John Ford. He wasn't a graduate of any drama school or college. His father was an Irish immigrant who kept saloons and made a living on the shady side of the law, selling liquor in a state that did not care much for Irishmen, or Catholics, or liquor. Jack Feeney grew up knowing what hard manual labor was, and brawling in the streets, and bending the knee in church. He did not fight in the First World War, but he later enlisted in the Naval Reserve, where he served for seventeen years. I don't know whether Ford ever met a saint in his life, but he did meet honest sinners. I don't mean people who sin in a fog of indifference or insensibility. Not much drama there. I mean men and women who sin and who know they sin, and who therefore may be found sometimes in a confessional, or sweating in prayer upon a bed of death.

Drama, alive

"In him we live and move and have our being," said Saint Paul to the pagans in Athens, as he tried to reveal to them the God they had sought in obscurity for so long. Well, the people in John Ford's world, the one he grew up in and the one he portrayed on screen, live out their stories within the great story, of man in the image of God, fallen, sinful, prone to meanness, hard of heart, vindictive, cowardly, yet still showing traces of that first glory; of man, infinitely precious, redeemed by Christ, fleeing from love and yet longing for it, withered at heart and yet ready to bloom in beauty with the least drop of healing water.

Without that Greatest Story Ever Told, all other stories grow dry and dusty. In the true Story, the one that Jack learned at Saint Dominic's Church, the next thing you do may be of eternal consequence.

He did not dabble much in sweetness. He gives us the real deal.

Lieutenant Colonel Kirby Yorke is stationed with his men near the Rio Grande. His son has left his boarding school out east to join the cavalry, and has been assigned to Yorke's platoon. Yorke's estranged wife, Kathleen, has traveled all the way out there to bring the boy back. They are man and wife — there's no divorce in a John Ford movie, as there was none in Ford's life; he died shortly after he and Mary Ford celebrated their fifty-third anniversary. The Yorkes are Adam and Eve; essential man and woman; his pride, her bruised feelings, his recklessness, her smothering need to protect. Man and woman: their very vices complement one another!

So Kathleen Yorke stands beside Kirby Yorke, because the men of the platoon have prepared a surprise. They welcome her with the old Irish folk song "I'll Take You Home Again, Kathleen." She supposes that her husband has put them up to it, but he's as surprised and embarrassed as she is. All through the song, he tries hard not to look at her, and she tries hard not to look at him, but neither one succeeds, although their glances do not meet. There is more electricity in that scene, more human longing, mingled with disappointment and guilt, grudges and nostalgia and regret, than in any hundred movies of pawing "lovers" going through the motions all the more extravagantly lest we notice that there is no heart.

That was John Ford, directing John Wayne and Maureen O'Hara, in Rio Grande.

The drama of the body

No director felt more keenly the holiness of manhood and womanhood. I don't mean that Ford gives us plaster saints, male and female. He did not dabble much in sweetness. He gives us the real deal. There's the bluff Beth Morgan, a good stout mother of six sons and a daughter. She's out in a snowstorm to challenge a pack of striking miners for threatening her husband because he would not join them. She shakes her fist, calling them "smug-faced hypocrites," because they dare to sit in chapel next to him. "There's one thing more I've got to say and it is this. If harm comes to my Gwilym, I will find out the men and I will kill them with my two hands. And this I will swear by God Almighty!"

There's Tom Doniphon, the cattleman who actually shot the outlaw Liberty Valance, saving the life of the rival for his sweetheart's love, and letting people believe that the rival had fired the shot. That man, a good but lesser man, is about to be nominated as the new state's senator. He doesn't want to accept, but Doniphon persuades him: "Hallie's your girl now. Go back in there and take that nomination. You taught her how to read and write; now give her something to read and write about!" So saying, Doniphon returns, drunk, to the pretty cottage on his ranch which he had built for Hallie when they should marry. He burns it to the ground, his loyal servant pulling him out of the flames. He dies destitute and forgotten.

What happens when you don't believe in manhood and womanhood? You may have strange creatures, interesting for a minute or two, but what real drama? Such men and women are like birch trees growing in a swamp, their trunks stunted, half of their limbs bare, and rotting from the roots. They aren't where and how they should be. They are alive — sort of.

Praise to the Lord, the Almighty

And what can you celebrate, if there's no purpose to life? John Ford grew up under the eaves of an Irish Catholic family. If time is liturgical, then we mark time best by prayer and song. All movies feature music; Ford's movies feature songs of the people. Some are songs of Irish rebellion, like "The Minstrel Boy"; some are patriotic anthems; many are hymns. Not the exalted alleluias of the biblical epics, though; they are hymns of ordinary people at worship, like "Shall We Gather at the River," and "Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah." Most moving it is to hear the rolling voices of men singing together — who work side by side, who often fight with one another, who shoulder together the burden of wresting a life from the earth.

Such songs are never mere decoration. They are expressions of solidarity. Ford saw that querulous mankind is only ever united from above. The outlaws become Three Godfathers and their lives are transformed, as they keep a promise they made to a dying woman to save her baby. The first thing the settlers do in Drums Along the Mohawk is to build a church, and their minister leads them in the defense of their lands against the British. When The Long Gray Line of cadets march to honor their old friend Martin Maher, the jack-of-all-trades who lived at West Point and became a father to generations of soldiers, they sing out in praise of Marty Maher-O, to the melody of "The Rising of the Moon," while Marty looks on and seems to see his deceased father and his wife, and the faces of lads who had died at war long ago.

Tell me that that could have been, without the faith! It's like suggesting that we could have roses without earth and water. For the skeptics, I'll end with a scene from The Long Gray Line. Notre Dame is playing a football game against Army. The Fighting Irish coach, Knute Rockne, has been perfecting a new weapon, the forward pass. Marty and his father have wagered on the game, Marty for Army and old Mr. Maher for Notre Dame. Needless to say, the Army team is baffled, and Notre Dame wins in a romp.

Mr. Maher collects his winnings from everyone, including Marty. "Let this be a lesson to you, my son," he says. "Never lay money against Holy Mother the Church."

No more should we.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: A Catholic to the Roots." Magnificat (January, 2015): 196-201.

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: A Catholic to the Roots." Magnificat (January, 2015): 196-201.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2015 Magnificat