Moral Illiteracy

- WILLIAM KILPATRICK

When the schools stop contributing to the fund of shared moral knowledge, the informal systems are put under enormous strain.

|

Martin Luther once described the human race as being like a drunk who falls off one side of his horse, gets back on, and promptly falls off the other side. This is a good description of what happened to moral education in the late sixties, except that it might be more accurate to picture two drunks on horseback. The first falls off the right side of his horse, and the second, taking note, avoids that calamity only to fall off the left side. Kohlberg avoided the lurch toward feelings only to tumble off on the other side the side of "critical thinking." But perhaps I ought to explain more fully why I think that was a mistaken direction.

It is becoming increasingly clear that we can't base moral education on a "follow-your-feelings" basis, but the critical thinking alternative still has broad appeal. A great many educators remain convinced that salvation can be found along the path of reason. What many of them fail to realize is that reason is on shaky ground when it stands alone. Aristotle emphasized the importance of acquiring good habits of thinking, but he also emphasized habits of feeling and habits of acting; and as we have seen, he stressed the importance of good upbringing. Plato, he believed, relied too much on the power of unaided reason.

Yet one of the main thrusts of recent moral education has been to set reason up on its own: to create, in effect, a culture-free morality. Kohlberg, for example, thought that children should become autonomous ethical agents, independent of family, church, and state. And he employed some powerful arguments in making his case.

The trouble with character education, with the whole "cultural transmission ideology," as he called it, was its potential for serving totalitarian causes. The methods sometimes employed in forming character were also the methods regularly used by tyrants in indoctrinating the masses. Flags and oaths and patriotic songs could stir noble sentiments, but they could just as easily stir base ones. And in the wrong hands, habit formation could be used to induce a habit of blind obedience. The Hitler Youth were uncomfortably similar to the Boy Scouts. Education, particularly moral education, should be free of all such emotional conditioning. It should respect the child's autonomy and his ability to make judgments independent of his culture. Who would be a good example of such autonomous moral reasoning? Kohlberg frequently cited Martin Luther King, Jr. (incorrectly, as I will explain).

Because it is such a persistent and influential theme in American education, this effort to make children into autonomous ethical thinkers deserves close examination. Ironically, some of the evidence against it comes from an extensive study of individuals who rescued Jews in Nazi-occupied Europe. The study, conducted by Samuel and Pearl Oliner and reported in their book The Altruistic Personality, showed that only a small minority of the rescuers were motivated by "autonomous" or "principled" ethics. The rescuers referred much more frequently to the way they were brought up, to the example of parents, or to the influence of religion. As the Oliners make clear, these people were not "moral heroes, arriving at their own conclusions about right and wrong after internal struggle, guided primarily by intellect and rationality." On the contrary, "what most distinguished them were their connections with others in relationships of commitment and care." In addition, these were people who, more than most, had internalized community and family norms. It was the bystanders and nonrescuers who were motivated by concerns about their independence and autonomy.

Why did the rescuers help? Here are some typical answers from, those surveyed:

I cannot give you any reasons. It was not a question of reasoning. Let's put it this way. There were people in need and we helped them.They taught me discipline, tolerance and serving other people when they needed something. it was a general feeling. If somebody was ill or in need my parents would always help.

When you see a need you have to help. Our religion was part of us. We are our brother's keeper.

The basic morality in this little homogeneous country is such that we have been told for generations to be nice to your neighbor, be polite, and treat people well. It came through during the war.

My father taught me to love God and My neighbor, regardless of their race or religion.

At my grandfather's place, when they read the Bible, he invited everybody in. If a Jew happened to drop in, he would ask him to take a seat. He would sit there too. Jews and Catholics were received in our place like everybody else.

Another finding of the Oliners is of equal interest. Most of the rescuers hardly deliberated before acting: "Asked how long it took them to make their first helping decision, more than seventy percent indicated 'minutes.'" The astonishing rapidity of their decisions is far different from the endless debates that take place now in American classrooms, and suggests that helping others had become a habitual mode of response. Their behavior, in short, seems to constitute an argument for traditional ideas about culture and character rather than a case for critical thinking.

How about Martin Luther King, Jr., as an example of moral autonomy? In some respects Kohlberg couldn't have chosen a less apt example. King was able to successfully resist and overcome the entrenched culture of Jim Crow in the South not because he had invented a new set of principles but because he appealed to a tradition that both preceded and transcended the tradition of Jim Crow. A minister and the son of a minister, he was steeped in Bible stories and the messianic traditions of the black church, along with its hymns and spirituals. When he attended Crozer Theological Seminary, he immersed himself in the writings of Plato, Aristotle, Mill, and Locke. In his speeches, he referred to Lincoln, to the Declaration of Independence, to Negro spirituals, to Moses and the Promised Land. His "Letter from Birmingham jail" even included a citation from the medieval theologian Thomas Aquinas on the difference between just and unjust laws.

King was, in short, the bearer of a tradition. He was able to mobilize white as well as black Americans because he was successful in reminding them of what they already believed about justice and common human decency. His demand was not that America create a new morality but that it live up to its best traditions and beliefs.

Nevertheless, the ideal of the culturally autonomous ethical thinker is not easy for educators to abandon. just the other day I read the following in a college textbook: "Morally autonomous people think independently and critically and make their own decisions about right and wrong . . . Martin Luther King's struggle for civil rights is an example of moral autonomy."

The critical thinking advocates are right to worry about the dangers of mindless patriotism and unthinking conformity. Where they go wrong is in their one-sided emphasis on the process of thinking. As Mortimer Adler points out, "There is no such thing as thinking in and of itself. All the thinking any of us do is thinking about one subject matter or another . . ." The question is this: Does freeing children from their cultural heritage really free them to think for themselves? Or only to think from within some other context such as the context provided by television? Once you deprive children of the content of serious culture, do they become their own persons or simply more in thrall to popular culture? How can we keep young people from being manipulated? One answer is to teach them critical thinking. But a better answer might be to teach them history along with literature, biography, and yes, scripture. Then they might have something with which to compare and contrast and judge something by which to call others, and themselves, to account.

One of the basic problems in moral education is to find the proper balance between content and process. Where should the emphasis be placed: on the content of the Judaeo-Christian-Western moral heritage, as was done in the past, or on independent thinking processes, as Kohlberg, Simon, and others would have it? The stress in recent decades has, of course, been on the second. Like the Cheshire cat, moral content has been in the process of disappearing from moral education. Not much of substance is left except, perhaps, for a ghostly smile.

But is content really that dispensable? Can we count on individuals to find out what they need to know about right and wrong once they've mastered certain processes? Should each generation of youngsters have to reinvent the moral wheel? Can they?

This controversy about moral education is really part of a larger controversy in American schools and colleges. A look at that larger dispute may help provide some perspective on the smaller. For a long time the general curriculum has been under the same pressure as the moral education curriculum that is, pressure to shift from an emphasis on content to an emphasis on process. Thus, it is argued, children don't need to learn to calculate so much as they need a process for thinking about math; they don't need historical facts so much as they need ways of thinking critically about the historical process. And the same applies to science, literature, and geography: the facts are not nearly as important as strategies for thinking about them.

Process-centered learning has been the rage now for several decades. What has been the result? One main effect is that students coming out of American high schools simply don't know many facts. Surprisingly large numbers of them can't locate the United States on a map of the world, can't distinguish World War I from World War II, can't identify Winston Churchill or Joseph Stalin. As for critical thinking, a 1989 survey of college seniors found that one quarter of them could not distinguish between the thoughts of Karl Marx and the United States Constitution.

One of the people who have written most cogently about this topic is Professor E. D. Hirsch of the University of Virginia. Hirsch's book Cultural Literacy created a stir and became a bestseller largely because he dared to make a list of 5,000 things that people in a literate society ought to know. Unfortunately, many of his critics tended to concentrate on the list and ignore the argument of the book. Hirsch's argument was basically this: Communities and cultures depend for their existence on shared knowledge. Without such specific knowledge and a shared ethos, it becomes difficult for members of a community to communicate and cooperate. Those without this knowledge will always be condemned to the margins of society. If the knowledge deficit becomes widespread, the culture will collapse.

A good deal of past and current history supports this hypothesis. Contrary to the claims of advocates of "cultural diversity," the actual history of culturally diverse societies is one of discord and bloodshed. Unless there exists a common language, common religion, or common traditions to bind them, people in such societies tend to be at each other's throats. By contrast, a country with many racial and ethnic groups can remain relatively peaceful for decades if these groups share the same language or values.

Such stability is endangered, says Hirsch, when educators neglect specific content in favor of critical thinking skills. And ironically, critical thinking itself will be one of the first casualties. A youngster won't learn to think critically if he doesn't have anything to think about. He won't learn to read or write very well either, nor will he have much grasp of history or current events.

Hirsch blames Rousseau for this state of affairs, Rousseau and John Dewey, who translated Rousseau's content-neutral ideas into American educational practice. Rousseau's name is on Hirsch's list, by the way, and we can use it here to illustrate his point. A literate person would not have to be told who Rousseau was. He would know that he was a Swiss philosopher who wrote about nature and Noble Savages and had some influence on the French Revolution. And he wouldn't have to know any more than that. That would be sufficient to follow the author's argument and ensure easy communication with him. Not knowing Rousseau's identity would not in itself, of course, limit someone's life (unless he happened to teach philosophy), but if enough of these content deficits existed in an individual, he would have difficulty entering the American mainstream. If he did not know North from South, or couldn't read directions on a package, or wasn't familiar with the law, he would be severely handicapped. Unable to participate in society, he would lose the sense of having a stake in it.

Just as it is important for a community to have a common literate culture, it is equally important for it to have a common moral culture. America has had a common moral culture for most of its history. In the past most people would have known of Adam and Eve's disobedience, the loyalty of Penelope and Telemachus, Abe Lincoln's honesty, the treachery of Benedict Arnold, the generosity of the couple in "The Gift of the Magi," the selfishness of Scrooge, the Ten Commandments, and the Twenty-third Psalm. None of this knowledge would ensure decent behavior, but it would be a good start. It would at least guarantee that people were speaking the same language. Like a common stock of knowledge, a common set of ideals seems necessary to any society that hopes to socialize its young.

But, as is the case with factual content, there now appears to be a decline in shared moral content. Let me give three examples from my own experience with college students.

The first incident happened five or six year ago during an exam. One of the questions concerned sex education and contained the word "abstinence." It was a poor choice of words. In a few minutes a student came up to my desk. "What's abstinence?" she asked. I thought for a moment, then said, "Oh, just substitute the word 'chastity.'" There was a brief pause, then "What's chastity?" she asked.

I mentioned the incident the next semester to another class, thinking that it might amuse them, but I was wrong again. Half of them had never heard of "chastity" either. I was reminded of Orwell's observation about the difficulty of practicing a virtue or principle when one lacks the very words for expressing it.

The second incident took place about a year later, this time in a graduate class of about twenty students. For some reason the topic of the Ten Commandments came up, and I decided it would be helpful to the discussion to list them on the board. I asked for some help from my students, only to find that they were unable to come up with the complete list. I don't mean that single individuals in the class were unable to do the task, I mean that the entire class working in concert couldn't do it.

The third incident occurred only recently in an undergraduate class. I was trying to draw a contrast between moral education that emphasizes Process and moral education that emphasizes content. I used Values Clarification as an example of the process approach because it offers a list of seven processes to use in forming values. The first guideline is "prizing and cherishing your values": the second is "publicly affirming your values"; the third is "choosing from alternatives"; and so on. It's an appealing list until you stop to realize that because of its lack of content, it can be used to arrive at any value position. Hider "cherished" his values, and "publicly affirmed" them. He could have subscribed to the whole list. I then suggested that a good example of a list with moral content would be the Ten Commandments or the Corporal Works of Mercy. But the latter term met with blank stares. No one in this class of forty or so had ever heard of the Seven Corporal Works of Mercy. This would be understandable in public institution, but I happen to teach at a Catholic university, and until recently, any student from a Catholic grade school would have known the Works of Mercy by heart. The list is:

- Feed the hungry.

- Give drink to the thirsty.

- Clothe the naked.

- Shelter the homeless.

- Comfort the sick.

- Visit those in prison.

- Bury the dead.

The list was drawn up on the assumption that if you were going to practice the virtue of charity, you ought to know what it involved. Of course, the list is based on incidents in the Bible and if you knew your Bible stories, you wouldn't need to memorize the list. Perhaps that was the reason for dropping it from the curriculum. The problem is, not many of today's college students seem to have much familiarity with Bible stories either. It is not uncommon to encounter students who don't know the story of the Good Samaritan or the Blind Man at the Well or Joseph and His Brothers. Charles Sykes, in his book The Hollow Men, recounts an anecdote about two university students who, though they were majoring in art history and studying Leonardo's The Last Supper, had no idea what the Last Supper was all about.

On the elementary and high school level the stock of knowledge about right and wrong has dwindled even more drastically. In 1985 Professor Paul Vitz of New York University reported the results of a comprehensive study of ninety widely used elementary social studies texts, high school history texts, and elementary readers. What Vitz discovered was a "censorship by omission" in which basic themes and facts of the American and Western experience had been left out. Of the 670 stories from the readers used in grades three through six, only five dealt with any patriotic theme; moreover, "there are no stories that feature helping others or being concerned for others as intrinsically meaningful and valuable." "For the most part," writes Vitz, "these are stories for the 'me generation.'" More seriously, religion and marriage institutions that have traditionally provided a context for learning morality are neglected: None of the social studies books dealing with modem American social life mentioned the word "marriage," "wedding," "husband" or "wife."

In one story by Isaac Bashevis Singer, a boy prays "to God" and later says "thank God," but in the sixth-grade version, the words "to God" are omitted and the expression "thank God" is changed to "thank goodness." Although many Americans pray and go to church, hardly anyone does in these ninety. books which are supposedly representative of American life. The importance of Christianity and Judaism in world history is similarly slighted. So are the religious motivations of the colonists and founders. Contemporary religious motivation is also almost nonexistent. For example, although Martin Luther King, Jr., is mentioned in many texts, only one bothers to note that he was a pastor and that black churches played a key role in the civil rights struggle.

This is a question not of asking textbooks to support or endorse religion or marriage or altruistic behavior but simply of asking them to recognize their existence and their social and historical importance. Since television presents a similarly skewed version of the world and because so many families are in shambles, many young people today have only the vaguest acquaintance with a common moral culture that was once available to all. How does this lack of background knowledge affect the everyday lives of young men and women? That's difficult to say. But we do know that many young people no longer realize that rape is wrong, and there are indications that much greater numbers are unaware that drunkenness is wrong. In his book Educating for Character, Thomas Lickona relates a Catholic university chaplain's observation that "college students rarely confess, as students once did, the sin of getting drunk (always considered a grave sin in Catholic moral theology)." Lickona continues, "It's not that today's students at this university never get drunk; many do. But apparently they do not think, as their predecessors did, that getting drunk is a serious moral wrong." Student drunkenness, as might be expected, is on the rise on college campuses across the country. On many campuses, it is the major problem. Along with the increase in drunkenness, there has been a corresponding increase in vandalism. Colleges spend hundreds of millions annually in repairing dorms that have been trashed by students.

Parents tend to blame schools for this state of affairs; schools tend to blame parents. Lickona quotes a fifth-grade teacher in a Boston suburb:

About ten years ago I showed my class some moral dilemma filmstrips. I found they knew right from wrong, even if they didn't always practice it. Now I find more and more of them don't know. They don't think it's wrong to pick up another person's property without their permission or to go into somebody else's desk. They barge between two adults when they're talking and seem to lack manners in general. You want to ask them, "Didn't your mother ever teach you that?"

The question of whether schools or parents bear most of the blame is not an easy one to resolve; it's a chicken-and-egg dilemma: Parents influence the children first before they go to school, but schools shape the children before they become parents. In any event, one thing is clear: When both fail to hand on the stock of knowledge, experience, and example that constitutes a culture's moral capital, children are in trouble. They begin to resemble not Noble Savages but simply savages. We can see the effects of moral illiteracy in the increasingly casual nature of crime. Police report that growing numbers of young lawbreakers seem to have no sense of human community, no point of contact. Many young murderers and muggers sincerely do not understand what they have done wrong or why they should be punished. They are outside the common moral culture. The cool, blank stare one sometimes encounters among young criminals is blank in part because the light of civilization has gone out of it.

This phenomenon is not simply a matter of insufficient education if by education we mean years of school completed. An illiterate and uneducated person can still be in touch with the moral inheritance of his culture. In The Moral Life of Children, Robert Coles shows how, even in the slums of Rio or in a sharecropper's shack in the rural South, children continue to learn the common ideals through church attendance, Bible stories, or the example of committed adults. In most societies, these informal attempts at inculcating moral culture are supplemented and complemented by the formal educational system. The two reinforce each other.

But when the schools stop contributing to the fund of shared moral knowledge, the informal systems are put under enormous strain. And when they start to break down, we begin to get a picture of what a society looks like when each person makes up his own "morality." By withholding the culture from a whole generation of youth, we are not helping them to "think for themselves," but only forcing them to patch together crude codes of behavior from the bits and pieces they pick up on television or in the streets.

What has been the reaction of educators to the decline of cultural literacy? One group, represented by people like Diane Ravitch, Chester Finn, and William Bennett, has called for a renewed emphasis on the unifying themes of Western culture and history. Another, considerably larger group continues to argue that critical thinking is more important than cultural content. In addition, there is a third group. The argument of this group the multiculturalists is that a multiracial, multiethnic society such as ours deserves a multicultural curriculum. In one version of multiculturalism, this means enriching the common culture by looking at the contributions of many groups; in another version, it means that black students study black history, literature, and culture while Hispanic students study Hispanic culture and so on, down the line. Multiculturalists also favor greater "diversity" in the curriculum but, once again, there is disagreement over what this entails. For some it means paying attention to a greater diversity of ethnic groups; for others it means giving more consideration to homosexuals and other "neglected" minorities. Several states are now considering revisions that would make their curriculums more diverse, and in colleges and universities, courses are already being monitored for diversity. It is, depending on how you look at it, education's latest crusade or its latest fad.

Being against multiculturalism is a little like being against motherhood indeed, opposition to it is a much more serious offense than opposition to motherhood. It is a difficult position to be in because, of course, there is a lot to be said for knowing your roots and understanding other cultures. In addition, America is a multiethnic society fed by many streams and tributaries. The more American students can know about this complex mix, the better.

For one group of multiculturalists sometimes referred to as "pluralists" that is what multicultural education means: a greater appreciation for the many strands that make up our common heritage. But many of the multiculturalists have staked out a more radical agenda. They don't want a richer common culture. Instead, they insist that no common culture is desirable. Critics of this "separatist" brand of multicultural education claim that its real mission is to discredit and destroy the common culture altogether. That was certainly the import of the much publicized affair at Stanford University in 1988 when students chanted, "Western culture's gotta go," and the administration responded by immediately watering down the Western Civilization Program. Since then, the attack on our so-called "Eurocentric" culture has been stepped up. It is widely criticized as being inherently racist, sexist, classist, and homophobic. More and more high schools, as a result, are dropping their European history offering and cutting back on American history until the textbooks can be rewritten.

What does this mean for moral education and for the common moral culture? According to historian Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., "if separatist tendencies go unchecked, the result can only be the fragmentation, resegregation and tribalization of American life." I fear that the loss of unifying moral ideals moral illiteracy will mean the same thing. We can see the effect of racial and ethnic separatism in the Soviet Union, in Yugoslavia, India, Sri Lanka, Iraq, Cyprus, Lebanon all over the world. It's a formula for violence. In Illiberal Education, Dinesh D'Souza makes a convincing case that the ideology and practice of multicultural separatism have already led to a marked increase of racial tension and hostility on university campuses. That, I suspect, is nothing compared to what will happen once the idea hits the schools and the streets.

Given the fractured nature of present-day American society; it seems the height of folly to think that what we need is an experiment in more fractionalization. In the extreme form of diversity education the form that now seems ascendant there are no transcendent themes or common commitments, just a plurality of groups fighting to establish their individual identities and claims. It is the opposite of the historic American goal of assimilation and integration.

It is also and this I believe is its central purpose simply another way of introducing relativism into American schools. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, journalists discovered that most American teenagers could not understand the significance of the event. For them the Communist bloc was just another culture with its own way of doing things. A substitute teacher in a Virginia suburb who polled his students in three advanced government classes a few years ago found that fifty-one out of fifty-three of them saw no moral difference between the American system of government and that of the Soviet Union. The two who could see a difference were both Vietnamese boat children.

From the extreme multiculturalist point of view, all cultures are created equal and no system of values is less valid than another except, of course, traditional Western values, which are highly suspect. Back in the mid-sixties the National Science Foundation funded at a cost of $7 million a series of textbooks for fifth graders called Man: A Course of Study (MACOS). The title is a bit odd in view of the fact that most of the units in the curriculum discuss animals. The one unit that deals with humans concentrates on the Netsilik Eskimos and pays much attention to their practices of cannibalism, wife sharing, and abandonment of the aged. In the words of one MACOS critic, these practices "are consistently portrayed as plausible and natural responses to the social situation."

MACOS was the social studies equivalent of Values Clarification. It was the philosophy of nonjudgmentalism. writ large: in other words, who is to say that what this group or that group of people does is right or wrong? Many of those who call themselves multiculturalists appear to be engaged in another, though far more comprehensive, attempt to install both cultural and ethical relativism into the heart of the curriculum. Teaching the language, art, and history of other societies seems to be the last thing on their minds. When one reads through the reports and recommendations of various committees on diversity, one experiences a strong sense of deja vu: the language of the reports is not the language of history and culture but the language of therapeutic education. A task force on minority education appointed by the New York State commissioner of education recommended in 1990 that Western civilization be deemphasized so minority students "will have higher self-esteem and self-respect." In a similar vein, exponents of "Afrocentric" education have begun to fabricate new versions of black history that will serve as a form of therapy for young blacks. Self-acceptance, rather than accurate knowledge, sets the agenda.

Such tampering with historical facts is not a problem for many advocates of diversity, since the notion of objectivity is seen as an imposition of Western culture. For some this applies not only to historical accuracy but also to scientific and mathematical accuracy. According to Professor Peggy Means McIntosh of Wellesley College, "exact thinking" is no longer desirable in science. Indeed, according to another educator, there may be "no right or wrong answer" to the question "How much is one subtracted from four?" That is the conclusion of "The Challenge of Multiculturalism," an article that appeared in American Counselor, and was highly recommended by some of my colleagues.

This is not reassuring. These ideas are taken far more seriously in educational circles than can be imagined by those outside the field. It is especially disturbing when we ask what such relativism might mean for moral education. If advocates of diversity think there is no right and wrong when it comes to simple math, what will they say about simple morality? Does cultural diversity imply moral diversity?

That appears to be the case for many influential diversity advocates. For example, one of the four preferred approaches to multicultural education identified by the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education is "the support of explorations in alternative and emerging lifestyles." Likewise, "skills for values clarification" is one of the four objectives for multicultural education listed by the National Council for Accreditation of Teacher Education. The buzzwords of humanistic psychology flow like a leitmotif through the literature of multiculturalism. One article states that "it is wrong to assume that one set of values is superior to any other," and that "nonjudgmental diversity is our strength as a nation." A book titled Schooling for Social Diversity invokes the phrase "tolerance for diversity" over and over. Other spokespersons for the movement speak of "holistic processes," "many realities," "multiple perspectives," and that old standby, the danger of "imposing values." Many multiculturalists also want to include sexual orientation as a form of diversity a tactic that removes homosexuality from the universe of moral judgment, and makes being gay equivalent to being Jewish or Chinese. Still other multiculturalists embrace a mystical primitivism. Wade Nobles, one of the featured speakers at the National Conference on the Infusion of African and African-American Content in the High School Curriculum, described the superiority of black Africans in the following terms: "We are the creative cause ... Black folk be. We be. We be doin'it. And our bodies tell us our physical essence and we don't listen."

This Atlanta-based conference, which included shell horns, drums, dancing girls, and bare-chested men in sashes, was not exactly a fringe event. The conference was sponsored by major publishers and was attended by more than a thousand teachers and administrators. Thomas Sobol, the New York State commissioner of education, addressed the meeting. Asa Hillard, a member of his task force, organized it. Its guiding document, The Portland African-American Baseline Essays, is, according to a recent Time article, "radically changing the curriculums of school systems all over the country."

The Atlanta conference is instructive. The reporter who covered it for the New Republic notes that western philosophy was described as "vomit," and "all the major religions of the world" were dismissed as "male chauvinist murder cults." He reports that "Plato and Aristotle were vilified" regularly during the two days of seminars. Plato and Aristotle are, of course, intimately tied to the tradition of teaching the virtues. Although most of Aristotle's science has been superseded, his ethical theory remains a key source of our present laws and moral codes. One wonders what it is about him that so rankles a conference of high school teachers. Is character also a Western cultural invention? Is virtue?

From the point of view of reestablishing cultural and moral literacy, these developments within the multicultural movement are not promising. The answer to the problem of cultural illiteracy is not to teach bits and pieces of other cultures while devaluing the Western tradition. Students are far more in need of simple perspective than they are of multiple perspectives. To assign equal validity to all cultures, customs, and values is to create the educational equivalent of a Tower of Babel. The result is bound to be both cultural and moral confusion.

Few cultures are free of racial or ethnic antagonisms. In many parts of the world, women are almost totally subject to men. Clitoridectornies are still performed among some African tribes. Wife beating is considered a minor matter in India and in some Latin societies. Child prostitution is not uncommon in some parts of the world. Slavery reportedly still exists in Mauritania and the Sudan. In dozens of societies, civil rights and free speech are only words. What is a child supposed to make of these multicultural items? What can he make of them if he is taught that there are no right or wrong ways, just different ways? What he needs is some way of making sense of such facts, of ordering and judging them. That is the point of transmitting a whole culture. Otherwise the child is adrift on a sea of relativism with no compass.

The Western tradition provides such a standard of judgment. And more than other traditions, it provides a standard for judging its own sins. As Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., points out, "The crimes of the West have produced their own antidotes. They have provoked great movements to end slavery, to raise the status of women, to abolish torture, to combat racism ... to advance personal liberty and human rights." it is to the Western standard that groups and individuals in other societies appeal when they seek to redress injustices within their own borders. It makes no sense to deprive our own children of that standard.

It is by no means a narrow standard. The Western tradition and in particular, the American tradition is open to a wide diversity of peoples, creeds, and cultures. "Paradoxical though it may seem," writes Diane Ravitch, "the United States has a common culture that is multicultural." No doubt there is room for improvement. And no doubt there is much to be learned from other cultures. But what needs to be asked is whether that is the sort of thing that anti-Western multiculturalists really want. One can look at the multicultural movement as an exciting and much needed new step in education, or as another, perhaps tragic, misstep. It takes a long time to build up a tradition of shared ideals and civilized habits, but it can be torn down in a surprisingly short time. Once it is gone, it is not easily restored.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

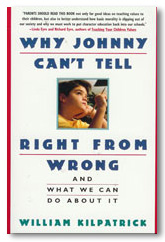

Kilpatrick, William. "Moral Illiteracy." Chapter 6 in Why Johnny Can't Tell Right from Wrong and What We Can Do About It. edited by J.H. Clarke, (New York: A Touchstone Book, 1992): 112-128.

Reprinted by permission of William Kilpatrick.

The Author

William Kilpatrick is the author of several books on religion and culture including Christianity, Islam, and Atheism: The Struggle for the Soul of the West and Why Johnny Can't Tell Right from Wrong. For more on his work and writings, visit his Turning Point Project website.

Copyright © 1993 Touchstone books