The Stories of Hymns

- FATHER GEORGE RUTLER

The History Behind 100 of Christianity's Greatest Hymns.

The treasury of sacred song is meant to be plundered by the faithful. In recent times, it has largely been left untouched, and in its stead very poor song has been taken up. Hymns, as individual compositions distinct from the Church's official collective prayer, have always been susceptible to aesthetic lapses, like any other form of art. More than a generation ago, C. S. Lewis complained that most hymns are "fifth-rate poetry set to fourth-rate music." The situation is worse now for two reasons: the degraded state of our culture and the banality of our liturgical life.

The treasury of sacred song is meant to be plundered by the faithful. In recent times, it has largely been left untouched, and in its stead very poor song has been taken up. Hymns, as individual compositions distinct from the Church's official collective prayer, have always been susceptible to aesthetic lapses, like any other form of art. More than a generation ago, C. S. Lewis complained that most hymns are "fifth-rate poetry set to fourth-rate music." The situation is worse now for two reasons: the degraded state of our culture and the banality of our liturgical life.

My purpose in writing this book was to restore attention to some of the finest hymns, in the hope that they might replace the miserable afflictions that keep cropping up in the baleful "missalettes," which are tokens of failure by their very existence (the Liturgy is not a didactic exercise to be read like a theater program) and appearance (their disposable form reflects the transitory quality of the contents). It seemed to me that hymns might be better appreciated if we knew a little more about the stories behind them: first of all, who wrote them and in what circumstances. In many cases, the background of a single hymn could supply the text for a whole book, so I remain frustratingly aware of the inadequacy of a few paragraphs to account for each. But these pages are offered only as intimations of the vast amount of material that the reader may want to explore on his own.

My choices, I freely admit and even boast, have sometimes been arbitrary, for, by embarking on such a project, one has to omit more than one selects. I have, moreover, been highly prejudiced in what I did choose because, although I have wanted to pick the most excellent in all respects, I have been guided by my own tastes and recollections. If an occasional choice lacks full obedience to the canons of high art, I plead that such was not meant to scandalize; it was the indulgence of a sense that the hymn represented some neglected virtue.

I deliberately call these songs "hymns" to distinguish them from run of-the-mill songs. We do not often make that distinction now. But there was a time when Catholics and Protestants alike understood the difference, which is why they did not impose secular idioms on music or text. When the distinction is blurred, the Church does not transfigure culture; the Church is usurped by culture. That is not a sacramental economy but its very opposite.

Starting off as the least of choirboys in the 1950s, it has been my good fortune to have had an acquaintance with many kinds of hymns in different places and circumstances. I was brought up as an Anglican — that is, as an Episcopalian — first in New Jersey and then in New York, in a social and moral climate made almost unimaginable for young people now by the radical changes of just a brief generation. It was our practice every Sunday to sit as choirboys in highly starched collars as men in frock coats ushered parishioners into Morning Prayer or Holy Communion. Weekday rehearsals were rewarded with a monthly allowance of $1.25 and an ice cream at the soda fountain across the street. While I have assiduously avoided writing autobiographical books or essays, the stories of one's favorite hymns often bring in strands of one's own story. So where such allusions and reminiscences may appear gratuitously in these following pages, it is because their remembrance was enjoyable to me and may find some sympathetic readers, too.

The hymn tradition is also part of the Church's biography, and so I have tried to show this by listing the hymns chronologically instead of according to their liturgical seasons or themes. Sometimes precise dating is difficult, but a general period can be given. The chronology is based on the texts rather than on the music, for a text may be sung to a tune from a different time, and to more than one tune at that.

Only because I was familiar with most of these hymns from an early age was I able years ago to take offense at their bowdlerization by clumsy editors and ideologues. I came to notice that, in almost every instance of "updating," solid theology was the victim. References to sacrifice, grace, sin, spiritual combat, and Christ's blood were replaced by insistence on kindness, altruism, and social enlightenment. The revisions of old hymns, and most of the inventions substituted for them, are uniformly sentimental: edifying in the worst condescending way, as well as redundant and gauche. This is to be expected of those who have been so unfeeling and rapacious in dismantling the fabric of our churches and the sacred texts used in them, for as selfish ambition has been called the lust of the cleric, so is sentimentalism the indulgence of the cruel.

Very often, people may sing a hymn without any clue as to how reduced the received version is. And, as hymns are poetry, it is decadent to alter their grammatical archaisms instead of rising up to them. We do not do it to Shakespeare, so neither should we do it to the friends of Shakespeare. Like children with sticky hands near fine furniture, a generation that has vandalized the sacred Liturgy should be prevented from laying hands on the great hymns.

The sorry state of hymnody is reflected in the architecture of the buildings in which the hymns are sung. The nervous Prometheanism of so many interpreters of the Second Vatican Council has abused architectural integrity. There are bright signs of classical revival, but these are conspicuous as reactions to the modernist spiritlessness whose dead hand still has executive influence. When it comes to music and architecture, "music in stone," what is particularly discouraging is the way so many in positions of authority seem tone-deaf to the problem; and what bodes particularly ill is the refusal of the few who do sense it to address it.

Whether or not those critics are correct who say that certain ecclesiastical documents of the Vatican II period were anodyne and even naïve in their measure of modernity, it cannot be denied that the generation that wallowed in euphoria is now, in old age, littering the landscape with architectural "Muzak in stone" in one last miscalculated attempt to be au courant. But it is like the spectacle of an aged man trying to impress the young with jargon he does not realize is already out of date. The Church is not faithful to her prophetic, priestly, and kingly offices if she does not inspire great art. For the Catholic, art is not superficial or extraneous, nor is it peripheral to the sacramental vision. To suppose it is exposes the worst kind of philosophical idealism in opposition to authentic metaphysical realism.

As has always been the case, these philosophical prejudices are rooted in mistaken Christolgies. In Lin neues Lied fur den Herrn (1995), then-Cardinal Ratzinger contended that "it is no longer Monophysitism that threatens Christianity, but a new Arianism or at least a new Nestorianism, parallel with a new iconoclasm." Since Vatican II, the charismatic movement has tried to redress this theological desolation, but too frequently it has seemed to be trying to do so within the context of its own miswrought idealism. Indeed, often its Manichean subtext has frustrated any attempt to renew worship in an authentically Catholic way. There have been impressive expressions of moral and doctrinal obedience, but the Manichean mood betrayed itself in its total aesthetic failure.

Charismatic enthusiasm has produced no art or music tempting to the iconoclast. And again, in a sacramental Church, this is not a mere defect; it is a radical disorientation. Although there are signs of improvement, the visitor to Rome will have a hard time hearing good music even in the noble churches there. But Sacrosanctum Concilium of Vatican II taught that "the musical tradition of the universal Church is a treasure of inestimable value, greater even than that of any other art" (no. 112). In relation to song, even worthy architecture cannot compensate for prosaic liturgies.

Nonetheless, the finest music of worship inspires, and in turn is inspired by, the vaults to which it soars. The self-consciously "modern" church building (usually an acoustical disaster) houses suburbanites who sing like Icarus about rising up on eagles' wings while dashing out to the parking lot. After a generation of synthetic and unrealized "renewal," there remains a reluctance to tell the truth about this situation, while dwindling congregations in their imposed aesthetic squalor sing painful metaphors about satisfying the hungry heart and breaking bread on their knees. Such was not the voice of John Damascene in the desert and Bernard of Clairvaux in the abbey. They knew that Christ makes the soul sing in the brightest and best way. If the following selection of hymns joins to these great orthodox souls a Lutheran such as the war-ravaged Melchior Teschner and the nonconformist John Milton, blind but singing his metrics, this is testimony to the wonders God accomplishes through those who seek His goodness even when they have not fully grasped the truth of it. I do not blush to say that some of these in their day wrote of doctrine more sturdily than nymph-like New Agers strumming guitars on "spirituality weekends."

If there have been no decent hymns written in the last generation, there is still reason to expect great ones in the next. Antiquity is not the justification of greatness; quality is. But if someone gushes that one's taste is as valid as another's, we have to reply with Catholic common sense what the Church has said in her finest moments at the city gates: If you think that, you are a barbarian.

Hymns, when they are worthy and worthily understood, should enhance the classical Liturgy which, by God's grace, will soon rise from its aesthetic stupor. A right understanding of the hymn form means a right understanding of prayer, the psychology of collective song, and the integrity of the Eucharistic action. Properly sung, the Mass has its own liturgical hymns. Sacred hymns were primitively held to be sacrosanct indeed: until the seventh century in the Roman Rite, only the priest sang the Our Father, and it stayed that way in the Mozarabic Rite; the Gloria was generally reserved for bishops until the eleventh century. The Creed was understood as a hymn from the fifth century; Pope Symmachus introduced the Gloria deliberately as a hymn in the early sixth century; and Pope Sergius made the Agnus Dei a hymn intrinsic to the Liturgy in the late seventh century. And all because a hymn was sung in the Upper Room.

The hymns that follow complement the Liturgy but are not part of it. The whole Mass itself is its own gigantic hymn, and it is only by indult that it is said at all instead of being sung. It is liturgically eccentric to "say" a Mass and intersperse it with extraliturgical hymns. Hymns may precede or follow the Mass, but they should never replace the model of the sung Eucharist itself with its hymnodic propers. In the Latin Rite, that model gives primacy of place to the Latin language and Gregorian chant, according to numerous decrees, most historically those of Pope Pius X in Tra le Sollecitudini and Vatican II's Sacrosanctum Concilium. The Church has normally reserved other hymns for other forms of public prayer, especially the Daily Office. And, of course, all hymns can be part of private prayer, following the Augustinian principle that he who sings prays twice.

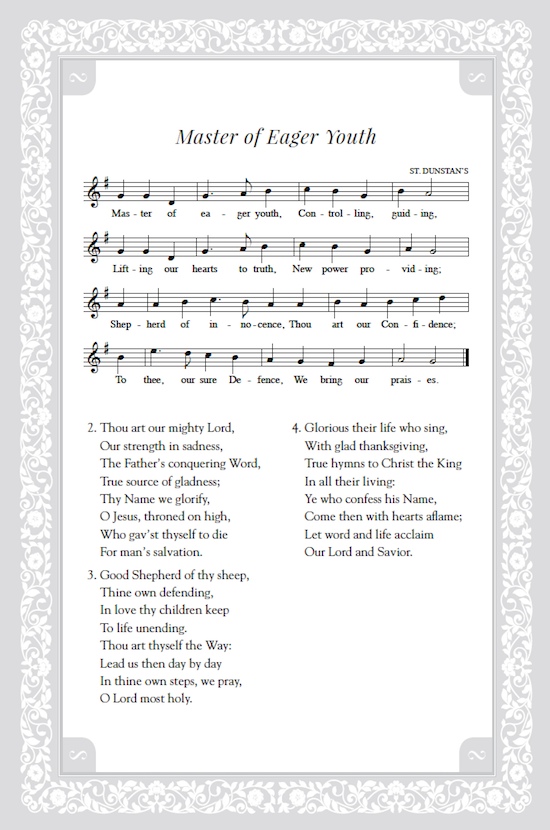

Master of Eager Youth

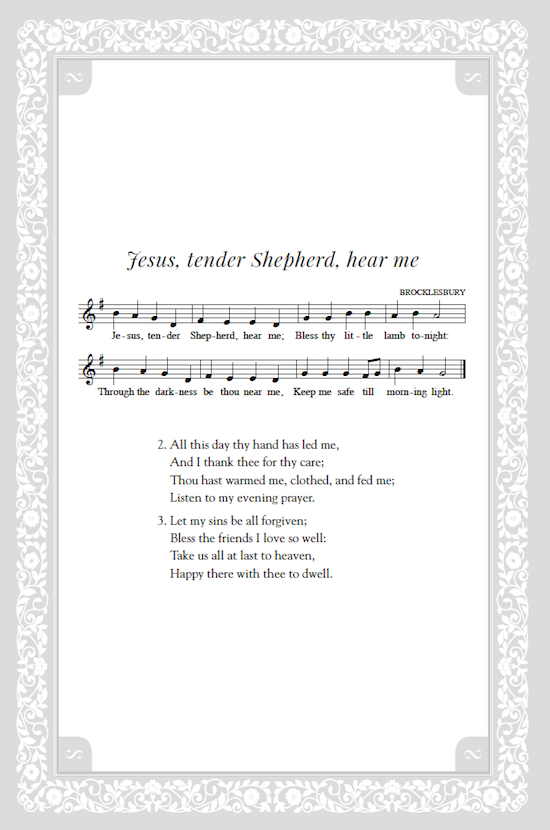

There is everything childlike and nothing childish about this piece, and that has to be credited in part at least to the gentle goodness of the two women who died so young after bequeathing it to the literature of hymnody. Mary Lundie Duncan, a Scotswoman born in 1814 in Kelso, near the birthplace of Henry Francis Lyte, died of a fever at the age of thirty-six. She wrote these words, and many like them, for her two children. Born in 1830, Charlotte Alington Barnard was an Englishwoman who wrote both music, including more than a hundred ballads, and two volumes of poetry, before dying in her thirty-ninth year. Her tune bears the name of Brocklesbury, her village near Dover.

"Evening Prayer" is another tune used with this hymn. Although it has a distinguished lineage, being an arrangement by the great Victorian John Stainer of opening bars from Beethoven's Andante in F, Barnard's tune is the one I and so many others grew up with in America, and in this instance the claims of the nursery take precedence over mature critics. The assertion that she wrote more than a hundred ballads is not exaggerated, given the popularity of ballads in their nineteenth-century revival. The ballad as a mannered form has various definitions and a very long and ambiguous history extending to well before the eleventh century. Dr. Johnson scorned many of them as unworthy doggerel, but their narratives could be politically potent, especially when set to catchy music. In the seventeenth century, Puritan and Cavalier governments alike regulated them and required licensing for ballad singers.

In the nineteenth century, a more erudite and less discursive ballade in France revived the troubadour tradition; but in England that century was conspicuous for the sentimentality of "drawing room ballads." Charlotte Barnard's best-known ballad continues to be the pleasantly lachrymose "Come Back to Erin," which joins the company of many beloved song tributes to Ireland not by Irishmen. What is called the "Common Meter" in hymnody has sources in the typical ballad structure, which, as in this hymn, consists in stanzas of four alternately rhyming lines, the first and third having four measures, the second and fourth having three, with each measure containing a doubled rhythm.

Duncan's text, like Barnard's music, is just the right sentiment for young children: tender but neither condescending nor trivial. They should not be beneath anyone who wants to be fit for the Kingdom of heaven. The author said these words to her children in the Manse in Cleish in Kinross-shire, where she lived as the wife of the local minister, William Wallace Duncan, whom she married in 1836. As she wrote most of her poetry by the year before her death, they were meant for those three years old and younger. We have them today only became Mary's mother collected them in a memoir in 1841. The image of the Good Shepherd is, on the other hand, among the oldest we have of the Lord in the art of the catacombs. Before I was old enough to be a choirboy, my favorite spot in Sunday School was seated beneath an engraving of the Good Shepherd, and I very much liked singing this pastoral hymn in a not very bucolic voice.

Jesus, tender Shepherd, hear me

Saint Clement of Alexandria (ca. 150-ca. 215) recorded these lines in his Peidagogos (The tutor) for use in his academy, which was at its height when this was written, around the year 200. Typically, he joined his own poetic praise of Christ with paraphrases of Scripture to dissuade the Gnostics from their heresy, challenging them with some of their own terms and phrases about the divine wisdom. For thirteen years, starting in 190, he headed the catechetical school in Alexandria, where such verse had of course a didactic purpose in the best classical sense, for there can be no true Christian learning that is not also Christian worship. That, in fact, is at the heart of the meaning of "orthodoxy," or "right praise." Origen (ca. 185-ca. 254) might be imagined among his pupils singing these words.

The present version, first published in 1938, is a very free translation by Francis Bland Tucker, an Episcopal clergyman born in 1895 in Virginia, where he served before taking a parish its Washington, D.C. The tune "St. Dunstan's" was composed on December 15, 1917, in a commuter train between Manhattan and Peekskill by Charles Winfred Douglas (1867-1944). Canon Douglas was a principal compiler of the hymnal that, for me, had been the hymnal. He was also musical director for a convent of Episcopal nuns in Peekskill, the Community of Saint Mary, whose stately buildings and venerable girls school enjoyed a splendid prospect from a cliff overlooking the Hudson. The buildings are now gone, and the view is blighted by a nuclear power plant.

As Archbishop of Canterbury, Saint Dunstan (909-988) had been an accomplished musician and a first-rate illuminator of musical manuscripts. Whether Canon Douglas named his tune for the saint or for his cottage in Peekskill called "St. Dunstan's" is a question of the chicken or the egg. Mention of such items prompts one to recall how the Waldorf salad was concocted by a chef of the old Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, on the site of the present Empire State Building, for a luncheon to benefit St. Mary's School.

Clement would find odder than all these details the world-weariness that has taken from many current youths the youthful joy that outlasts you when it comes from Christ. When I sang this as a boy, I had not the slightest idea who Clement was or where Alexandria was, but I was glad to be young, with older people telling me that I had a Divine Master. In the full version of the hymn, Clement calls Christ Stomion Polone Adaone (Bundle of the untamed colt), and that He was to me.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father George W. Rutler. "Preface." The Stories of Hymns (Irondale, AL: EWTN Publishing, 2016): 3-7.

Father George W. Rutler. "Preface." The Stories of Hymns (Irondale, AL: EWTN Publishing, 2016): 3-7.

Reprinted with permission from Father George W. Rutler and EWTN Publishing.

The Author

Father George W. Rutler is the pastor of St. Michael's church in New York City. He has written many books, including: The Wit and Wisdom of Father George Rutler, The Stories of Hymns, Hints of Heaven: The Parables of Christ and What They Mean for You, Principalities and Powers: Spiritual Combat 1942-1943, Cloud of Witnesses — Dead People I Knew When They Were Alive, Coincidentally: Unserious Reflections on Trivial Connections, A Crisis of Saints: Essays on People and Principles, Brightest and Best, and Adam Danced: The Cross and the Seven Deadly Sins.

Father George W. Rutler is the pastor of St. Michael's church in New York City. He has written many books, including: The Wit and Wisdom of Father George Rutler, The Stories of Hymns, Hints of Heaven: The Parables of Christ and What They Mean for You, Principalities and Powers: Spiritual Combat 1942-1943, Cloud of Witnesses — Dead People I Knew When They Were Alive, Coincidentally: Unserious Reflections on Trivial Connections, A Crisis of Saints: Essays on People and Principles, Brightest and Best, and Adam Danced: The Cross and the Seven Deadly Sins.