A Clean Heart Create in Me, O God

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

One summer when I was twenty-four, I traveled alone in Italy, on a shoestring, as a young man can who doesn’t mind sleeping in the occasional train station.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

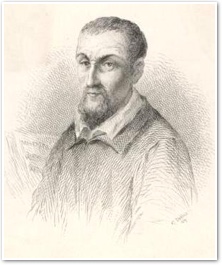

Gregorio Allegri

Gregorio Allegri1582-1652

Back then I did not understand more than a trace of what I was looking at, even when I once spent an uninterrupted hour in the Sistine Chapel. I gazed anyway, especially at the commanding gesture of God the Father, in Michelangelo's astonishing conception, as he is about to touch the finger of Adam and make of him "a living soul," noble, intelligent, and capable of imitating the art of God who made him. Capable also of falling into sin and foolishness, as I had done, I and all mankind.

Had I been in the same place in 1770, during Holy Week, I might have caught sight of a wigged man from Austria, standing beside his young son, Wolfi. "My son doesn't see," he would tell Pope Clement XIV, when the boy was accused of having pirated the "secret" music sung by the choir on Spy Wednesday. He didn't mean that the boy was blind. Rather, the boy was all ears; and, his spirits raised by the mysterious polyphonic Miserere mei, he committed it to memory. That night in their hotel, where they shared a single bed, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart couldn't sleep, so he got up and wrote the music out, five simultaneous interweaving melodies for bass, tenor, alto, and two semi-choirs of boy sopranos. Not sure he had gotten it all right, the boy returned to the Sistine Chapel for services on Friday, and made one or two minor corrections.

That eventually got him in some trouble, because nobody was supposed to share the music, which was not written down, but had been passed from one choirmaster to the next for over a century, each choir improvising and embellishing. The pope summoned the Mozarts to his court, where Wolfgang gave him proof of his innocent intentions and of his prodigious powers. Clement was delighted.

Another boy, another age

But we might also go back almost another two hundred years, to 1590.

"Gregorio," said the old master, "where do you enjoy singing better? Look all around you," and he gestured toward the grand ceiling. "Here is the pinnacle of art. Your church of Saint Louis is fine, but nothing can compare with this." It would be about ten years before another Michelangelo, surnamed Caravaggio, would bestow upon the chapel walls of San Luigi dei Francesi his dramatic paintings from the life of Saint Matthew. Yet for sheer complexity and power, and the vastness of the vision, no one could excel Michelangelo, and this place too was where the Vicar of Christ himself might come to say Mass or to pray.

That sort of thing was the rule all over Europe, as men devoted to God taught boys and other men to make real the sacred music they or others had composed.

"Master," said the boy, "I wish this chapel were my home!"

"You'd sleep on the stone floor, come un monello?" the master smiled.

"If I could wake up and hear your music, master."

"And where did you learn to say things like that!"

"Master," said the boy, "I want to make music like yours someday."

"Oh," said Master Pierluigi, "you're not content just to sing. Have you written anything?"

"Yes, sir," said the boy.

The boy, Gregorio Allegri, may have been the last real student that Master Pierluigi da Palestrina ever had, but he would go on to compose music after the manner of his teacher. Palestrina was a priest, and so was the boy Gregorio's choirmaster at San Luigi, Giovanni Maria Nanino, and the old master himself had sung at San Luigi too, when he was a boy. That sort of thing was the rule all over Europe, as men devoted to God taught boys and other men to make real the sacred music they or others had composed. We have nothing comparable now. It wasn't that the boys were invited to participate in it now and then. Without the children, the music was strictly impossible — even in the Sistine Chapel.

The priest and composer

Nowadays a boy with talent may wear out his days and smother his soul in school, but Gregorio Allegri had Palestrina and the brothers Nanino for his teachers, all of them men of God, and Allegri in turn was ordained a priest, as was his kid brother Domenico; all singers, priests, and composers. That was bound to lift up the heart and expand the spirit. Imagine if your soul had the heavens above for its beholding, and the psalms of David and the words of Jesus for your meditation, and the art of Michelangelo, Perugino, Raphael, Luca dei Signorelli, and other Renaissance masters for your eyes, and the music of Palestrina and his fellows for your mind, your memory, and the energy of your body and voice as you sing. We shouldn't be surprised that Gregorio would devote his life and his art to God.

We don't have all of his works, not by a long shot. We don't know much about his life. He seems to have been on the shy side, a man of exceptional purity. Some people say that Allegri wrote the first piece for a string quartet, which may be true, since of all musical instruments the viola, the violin, and the cello "sing" most like the human voice, and Allegri, like his fellows and teachers, composed primarily for the human voice, for sacred settings, without excessive ornamentation.

The most famous moment in the music comes when all is suddenly hushed for a sole boy treble, who soars — all the way to Top C, as the melody has come to us from an embellishment in the 19th century.

That brings me to the music that Mozart heard. It is a polyphonic setting of the great penitential psalm of David, "Have mercy on me, O God, in thy great goodness," after the Prophet Nathan had accused him of his adultery with Bathsheba and his attempting to cover it up by having her husband, the faithful Uriah the Hittite, exposed in battle: lust, bloodshed, conspiracy, and deceit. A tenor chants the first part of a verse, and then the choir enters for the second part, antiphonally, with either of two polyphonic endings, alternating from verse to verse. The most famous moment in the music comes when all is suddenly hushed for a sole boy treble, who soars — all the way to Top C, as the melody has come to us from an embellishment in the 19th century.

Let's think about that. A pure soul, a Catholic priest who in his own person knew nothing of adultery and murder, composed a haunting choral piece wherein a mere boy, also innocent of such sins, would leap to the heights of music and devotion, singing, in Latin, that God might create a clean heart in him, and a right spirit renew within his inward parts: visceribus meis, soaring to that high note on the penultimate syllable of the line.

It's like seeing a small child beating his breast at the Confiteor, saying that he has "greatly sinned," through his fault, through his fault, through his most grievous fault. Who knows how many hardened sinners might feel the melting fire of the Holy Spirit at the instance of such a prayer, from such lips?

Go and do likewise

The power did not escape another great man, a child prodigy in his own right. In 1831, Felix Mendelssohn attended the Holy Week services in the Sistine Chapel and recounted his experience. The words of the Passion were chanted: "Now he that betrayed him gave them a sign," continuing until "the same is he, hold him fast." Then everyone fell to his knees, and one voice sang, "Christ was made obedient for us even unto death." The congregation prayed the Our Father in what Mendelssohn called a "death-like silence." Then, he wrote, "The Miserere commences, with a chord softly breathed by the voices, and gradually branching off into two choirs. This beginning, and its first harmonious vibration, certainly made the deepest impression on me. For an hour and a half previously, one voice alone had been heard chanting almost without any variety; after the pause came an admirably constructed chord, which has the finest possible effect, causing everyone to feel in their hearts the power of music; it is this indeed that is so striking. The best voices are reserved for the Miserere, which is sung with the greatest variety of effect, the voices swelling and dying away, from the softest piano to the full strength of the choir."

Mendelssohn, though not Catholic, was, like so many artists, composers, poets, architects, and novelists of the 19th century, going to Italy to drink from the springs of its inspiring culture. We might trace a line from Palestrina to Allegri, from both to Bach, from Bach to the Catholic Mozart who helped to rediscover him, from Mozart to Mendelssohn, and from there to our times, even to that day in 1983 when I, knowing nothing of all of this, gaped at the works of Michelangelo, ignoring the tourists around me.

Dear children of our holy Mother the Church: We've been granted many centuries of beauty and wisdom. Should we forget? Then indeed we might have cause to sing, "Have mercy on me, O God!"

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: A Clean Heart Create in Me, O God." Magnificat (January, 2019).

Anthony Esolen. "How the Church Has Changed the World: A Clean Heart Create in Me, O God." Magnificat (January, 2019).

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2019 Magnificat