Tom Wolfe’s vanities

- JOSEPH EPSTEIN

A review of "The Bonfire of the Vanities" by Tom Wolfe.

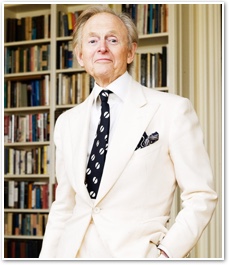

Tom Wolfe

Tom Wolfe1930-2018

American English is deficient in not having a word that, if not the antonym of carpetbagger, at least suggests the idea of traffic going the other way. The carpetbaggers, it will be recalled, were those northerners who headed south after the Civil War to cash in on the Reconstruction. The word I seek would describe those southerners — southern writers, specifically — who, nearly a century later, headed north to cash in by describing the period of American history that may someday go by the name of the Deconstruction. I say north, but I really mean Manhattan; I say Deconstruction, but I really mean that scrambling of ideals and morals, that blurring of meaning about fundamental matters, which has been so notable a feature of contemporary life in recent decades. Truman, Bill, Willie, Tom, these southerners headed north as if toward home, to play off the title of an autobiography written by one among them. To Manhattan southern writers have brought their dreams, their subtle feeling for the filigree of status life (for outside a beehive, no place is more abuzz with status than a southern town), and their churning literary ambition.

Many of these southern writers scored early and heavily, and some among them ended sadly and boozily. Midge Decter, who worked as an editor at Harper's at a time when it was dominated by southern writers, once remarked that these southerners could be very impressive, but, funny thing, they always seemed to want to stop for a beer. That is no mere mot, for alcoholism, from Thomas Wolfe on, has long plagued southern writers. But between Thomas Wolfe and Tom Wolfe there is a vast difference, and the latter, a southerner from Richmond, Virginia, appears never to have stopped for a beer or anything else, except a Ph.D. in American Studies at Yale, on the way to a quite extraordinary career in contemporary American letters. And in Tom Wolfe's case, a career, in the root sense of a course of continued progress, it has distinctly been.

A careful caretaker of this career, Tom Wolfe may be the only writer since Mark Twain to dress for the job. Two white-suited southerners, Twain and Wolfe resemble nothing so much as characters who have somehow wandered off the stage of a production of Jerome Kern's Show Boat. In another sense, of course, a showboat is a show-off, and there is a strong element of calling attention to himself, of sheer showing off, in Tom Wolfe's work. Plainspoken and decorous in his personal utterances, Wolfe has written as he has dressed, which is gaudily. If exclamation marks were dollars, he would already have spent a million. If italics were neon, his prose would long ago have suffered a power outage. If punctuation could be patented, he could lay claim to the double-decker, triple-length ellipsis, which looks like this: ::::::::: Along with flashy punctuation, Wolfe commands a vocabulary made up of up-to-the-moment street talk, academic locutions, and fairly arcane medical terms that, mixed together, often result in an amusing verbal salad. Abrupt shifts, wild transitions, loony interjections, and other prose pyrotechnics are frequently set off just to make certain that no one sleeps while reading Tom Wolfe's prose.

If Wolfe's manner can be raffish, his method has always emphasized realism. Realism in Tom Wolfe's journalism has meant a concentration on the grain and texture of everyday life as brought out in its concrete details. It was the concentration on detail, as Wolfe himself has argued, that gave power to the novels of Dostoevsky, Dreiser, Dos Passos, and other realists, for the element of reporting has always been crucial to storytelling of all kinds. As a newspaper reporter — once out of graduate school, with an appetite for the real world that only graduate study can give, Wolfe worked for The Washington Post and then for The New York Herald-Tribune — Wolfe trained himself to pick up such details. I say "trained," but more likely he had a natural instinct for them, especially for those details that are important counters in what he once termed "the statusphere." Wolfe can determine the status nuance of the frames around the photographs atop the piano in the apartment of Leonard Bernstein, of the sound a Bonneville car door makes when closing, of the length of a radical's sideburn. This may seem to some people pretty small game, utterly trivial, mere kakapitze, but I, who find it all fascinating, am not among them.

Tom Wolfe also early showed a powerful aptitude for insinuating himself into the point of view of the people he wrote about. That takes work — "legwork," the old-line journalists used to call it — and, if you do it with as ambitious a range of characters as Wolfe has dealt with over the years, it also takes imagination. Point of view had long been the almost exclusive province of the novelist, but Wolfe was among those who first brought it into journalism. "The idea," he has written, "was to give the full objective description, plus something that readers had always had "to go to novels and short stories for: namely, the subjective or emotional life of the characters." Wolfe used a straight point of view, shifting points of view, stream of consciousness, and every other literary device he could bring into play to enhance and enliven his journalism. The point was to lend journalism the density and intensity of literature while retaining the authenticity and excitement of dealing with real people and actual events.

This phenomenon of applying novelistic techniques to journalistic subjects came to be called the New Journalism. Tom Wolfe never claimed to have invented it, though he was its most energetic practitioner. A lot of it, you might say, was going around in the early 1960s. Some of the most prominent New Journalism was written by writers who were neither new nor trained as journalists. Truman Capote's In Cold Blood (1966), an account of the massacre of a prosperous Kansas farm family, was billed by Capote, who was a publicity genius, as a "non-fiction novel." Later, in 1967, Norman. Mailer produced a book entitled The Armies of the Night, which he styled, in a subtitle, History as a Novel, the Novel as History, which is quite as nonsensical as it is inflated, apart from the obvious fact that Mailer, too, was using novelistic techniques — including writing about himself in the third person — in the production of autobiographical journalism. Gay Talese, Jimmy Breslin, and Hunter S. Thompson were also sometimes spoken of as New Journalists. But, as with all things that have the misfortune to be called new, the New Journalism, after a pretty good run of a decade or so, ran out of excitement.

Wolfe has argued that the New Journalism was able to generate the excitement that it did because the novel, after World War II, in effect vacated the premises by abandoning realism for sheer introspection or academic games-playing. True enough, there has, in American fiction, been a genuine embarras de pauvreté. True, too, many an American novelist eschewed the great subject of American society — and at a time when that society was undergoing the social whiplash of the Sixties and Seventies — to contemplate rather exclusively their own navels and parts below. In a lengthy introduction to an anthology entitled The New Journalism, Wolfe wrote:

. . . about the time I came to New York, the most serious, ambitious and, presumably, talented novelists had abandoned the richest terrain of the novel: namely, society, the social tableau, manners and morals, the whole business of "the way we live now," in Trollope's phrase .... Balzac prided himself on being "the secretary of French society." Most serious American novelists would rather cut their wrists than be known as "the secretary of American society," and not merely because of ideological considerations. With fable, myth and the sacred office to think about — who wants such a menial role?

The novelist, in this reading, dropped the family jewels, leaving the (new) journalists to pick them up and pocket them for themselves.

After remarking that "understatement was the thing" among journalists and literati, Wolfe wrote that "by the early 1960s understatement had become an absolute pall." In his own journalism understatement was clearly out. It was out, too, in his discussion of the merits of the New Journalism, where Wolfe avoided it like Brooks Bros. At one point, claiming that the New Journalism offered all the techniques of literature along with the simple but overpowering fact that what the New Journalists wrote about "actually happened" (italics certainly not mine), Wolfe went on to claim that the New Journalist "is one step closer to the absolute involvement of the reader that Henry James and James Joyce dreamed of and never achieved." Now that, no question about it, is really pushing it.

Wolfe, who can compare the tedium of graduate school with "reading Mr. Sammler's Planet at one sitting, or just reading it," is rather more kindly disposed to the creators of New Journalism and neglects to mention criticisms against it. Jimmy Cannon, an old journalist, once remarked that "my main objection to some of them [the New Journalists] is that they make up the quotes. They invent action. When I was a kid we used to call it faking and piping, smoking the pipe, opium smoking." That the New Journalists make things up may or may not be true — it is usually unprovable in any case; more interesting is the related problem of the reader's not being able to determine whether or not the author, the New Journalist, actually saw what he is reporting or is instead reporting what other people have reported to him that they saw. An example will perhaps make the point less abstract.

In The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), Wolfe's New Journalistic account of the pharmacological adventures of the novelist Ken Kesey and those who gathered around him in the early and middle 1960s, there appears a lengthy paragraph that, for sheer loathsomeness, has been accorded a place in a mixed-media production that sometimes plays in my mind that I think of as Great Moments From The Sixties. It is a paragraph devoted to a gang-bang — not, technically, a gang rape, in which the victim is unwilling — of a married woman (she is described in the paragraph as "just one nice soft honey hormone squash") by a band of Hell's Angels. Further details are not required for anyone with the least scintilla of imagination, though Wolfe supplies details in sufficient abundance to make one feel that, next to what went on in the shack in which this took place, hell itself would seem no worse than Club Med. But since we are talking about what actually happened, it seems fair to insist upon knowing if the man reporting it to us was actually there. And if he was actually there — I could be wrong, but I suspect that Wolfe wasn't — then is the quality of his description, which is meant to be objectivity set out before us through the point of view of the Hell's Angels, appropriate to the occasion? I don't think this is a trivial question.

Tom Wolfe is pre-eminently the chronicler of those people who do not so much live lives as they live lifestyles — which is to say, of people who do not live life very deep down or authentically.

One could raise other questions and objections about the New Journalism: because of the large outlay of energy in legwork it requires, it seems to be chiefly a young man's game; because of the equally large outlay of time required to do what Wolfe has called "saturation reporting," large expense accounts or publishers' advances or independent wealth are necessary; because the amount of snooping required is great, not to speak of that special journalistic appetite for biting the hand that feeds you (the hand, specifically, of one's subject, whose permission one needs for interviews and for merely hanging around), not every literary talent has the temperament needed for New Journalism. But these objections have been rendered moot by time and nugatory by fashion. For the New Journalism the caravan passed years ago, and even the dogs have stopped barking.

If interest in the New Journalism has faded, interest in Tom Wolfe has not. He has been able to ride out the waves of fashion on the surfboard of his own remarkable talent. Fashion is after all Tom Wolfe's subject. By identifying and then (usually) attacking what is currently fashionable, he has himself become not quite fashionable but certainly famous. No other writer of our day has put more phrases into contemporary speech. "Radical chic," "mau-mauing," "The Me Decade" are all Wolfe's coinages; the "Right Stuff," which he took from the speech of test pilots, today has the currency of full-blown cliche. "Wolfeian" has not thus far become a commonly recognized adjective, perhaps owing to the existence of Thomas and Nero Wolfe, but I myself have long begun to think of the phrase "to cry Wolfe" as shorthand for spotting a hot trend, shift in the current social scene, or new — my pen trembles in my hand as I prepare to set down the detested word — "lifestyle." Of the spread of the use of LSD in and around San Francisco in the early 1960s, and of the origin of the so-called Trip Festivals that initiated the psychedelic discotheques ("Civilization and its discotheques," Anthony Hecht once noted), Wolfe, in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, wrote: "But mainly the idea of a new life style was making itself felt. Do you suppose this is the — new wave . . . ?"

Tom Wolfe is pre-eminently the chronicler of those people who do not so much live lives as they live lifestyles — which is to say, of people who do not live life very deep down or authentically. They are often very savvy, even self-reflecting, about the way they live, but finally the style dominates the life. To this day I can recall a brief piece about an advertising man alienated from his son that appeared in Tom Wolfe's first book, The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby (1965), of whom Wolfe wrote that he, the man, whose name is Parker, called the short-brimmed, hard-crowned hat of the day a "Madison Avenue crash helmet." "He," Wolfe notes, "calls it a Madison Avenue crash helmet and then wears one." Of such people Tom Wolfe has made himself the leading connoisseur.

As a journalist, Wolfe has played the reporter who brings the news, some of it hot and new (as in the book on California drug culture), some of it not so new but interesting nonetheless because it has been wrongly neglected by others (as in The Right Stuff, his book on the heroism of American test pilots and astronauts). Easily the most stir-causing single piece of journalism Tom Wolfe has written in this mode is "Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny's," which appeared in New York early in the summer of 1970. That piece is, put simply, a devastation; it features that good old democratic joke, the rich making tremendous fools of themselves. In this case, it will be recalled, the fools in question were the guests of Leonard Bernstein and his wife Felicia — greater fools still, for allowing Tom Wolfe past their front door — who organized a fund-raising party for the most militant of 1960s militant revolutionary groups, the Black Panthers, in their, the Bernsteins', Manhattan apartment. It was an event that can be likened to a French comte and comtesse inviting Mme. Defarge and a few of her friends over to dinner, then calling back and reminding her not to neglect to bring along the guillotine. Doing one of his point-of-view turns, Wolfe writes:

God, what a flood of taboo thoughts runs through one's head at these Radical Chic events .... But it's delicious. It is as if one's nerve endings were on red alert to the most intimate nuances of status. Deny it if you want to! Nevertheless, it runs through every soul here. It is the matter of the marvelous contradictions on all sides. It is the delicious shudder you get when you try to force the prongs of two horseshoe magnets together . . .them and us...

The political consequence of "Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny's" was to take radical politics off the celebrity social calendar. By giving the disease a name, and by exhibiting its symptoms through the powerful microscope of literary ridicule, Wolfe demonstrated the egregious contradictions, the spiritual vulgarity, the sheer idiocy inherent in reverse social climbing of the kind the Bernsteins and their guests thrilled to that night in Manhattan. After Wolfe's article had appeared in print, radicalism, at least as it was shown in the sexier news media, seemed to lose momentum and never again to have quite the same social luster.

Before the article about the party at the Bernsteins', it would not have been easy to say what Tom Wolfe's politics were. Writing about custom car designs, Pop Art collectors, stock-car drivers, rock'n'roll impresarios, the girl of the year, and other such subjects, Wolfe's political views did not seem a matter of pressing interest. Where they first became interesting was in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, his book about Kesey and the drug culture. LSD, after all, is not a subject upon which it is possible to remain neutral, or so at least one would have thought.

Yet in that book, which exhibits prodigious reportorial skills, one couldn't resist asking where Tom Wolfe himself stood in relation to the patent destructiveness of the drug culture. One couldn't resist asking because, in truth, after more than four hundred pages, one still didn't quite know. Wolfe's admiration for Ken Kesey, which runs very high, comes through in the book without equivocation. But did the worldly, then-young journalist also buy the mad talk about the higher consciousness that drugs were alleged to make possible? Was our author, to use a phrase much used in the book, himself on or off the bus — for or against what he was describing? Early in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Wolfe wrote: "I feel like I am in on something the outside world, the world I came from, could not possibly comprehend, and it is a metaphor, the whole scene, ancient and vast, vaster than . . ." By the end of the book, Wolfe has not filled in that ellipsis; and those may be the most unsatisfactory three dots in contemporary journalism.

After "Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny's" appeared in New York, Tom Wolfe's own point of view ceased to be problematical in his writing. He also seemed to become interested in politics. Perhaps writing that article helped him to understand that politics, for so many people, fell within the domain of "lifestyle" — proper political views being for them the ideational equivalent of proper clothes, food, and furniture — and could no longer be ignored by a writer with his literary ambitions. Perhaps he had something like a political conversion brought about by an awareness of the extreme contradictions inherent in contemporary left-wing views. Certainly publishing his article on the Bernsteins' party, which blew a very shrill whistle on left-wing absurdity, made him a permanent enemy of the Left. The article also gave him national fame of a kind that nothing he had hitherto written had brought. Before writing "Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny's," Tom Wolfe was a stylish journalist; after the article, he was something of a celebrity, whose point of view, far from needing to be suppressed for vague, possibly bogus, journalistic reasons, was now of considerable interest in its own right.

Throwing out the baby with the bathwater, along with being a cliché, is an old story; but when Tom Wolfe gets done, as in these two books, he has also removed the plumbing.

Wolfe's own status changed from journalist — "working pest," as a wag I know likes to put it — to something akin to social observer. He continued to do a certain amount of saturation reporting of the kind he had earlier vaunted as the literary wave of the future — certainly The Right Stuff (1979) is a work of this kind — yet he now also did a turn or two at elaborate opinionation. In this realm, Wolfe was not about to fall into the journalistic trap of becoming a pundit; "paralyzing snoozemongers" is the way he had earlier described such pundits as Walter Lippmann and Joseph Alsop. Status and her sister Snobbery remained his key subjects, and comedy in describing their operation in the contemporary world his chief gift. As a social observer, he would charm through comic outrageousness.

Success, along with begetting success, begets confidence. It took confidence of high magnitude for Wolfe to take on his next subject, which was the contemporary art scene. The Painted Word (1975) is a comic sociology of that scene. In part, it delineates the relation of le haut monde — or tout New York — to visual art as "Radical Chic" delineated its relation to radical politics. In both instances an essential fraudulence lies at the heart of the relationship, with both radical politics and what passes for advanced taste in art allowing those rich and socially ambitious enough to dally with them to feel spiritual grace and gorgeousness of soul of a kind that sets them well above their class and even above the money that made it all possible to begin with. Wolfe plays all this for laughs, of which, as always when big money and social aspiration and culture get together, there is no paucity.

The Painted Word is an example — an extended essay on modern architecture, From Bauhaus to Our House (1981), is another — of Tom Wolfe operating in his emperor-has-no-clothes mode. He can be highly entertaining in this mode, except that he seems always to want to push things rather further than he ought. It is not sufficient to show that the emperor is undressed; it must also be pointed out that he has no knee-caps, clavicle, scrotum. Thus Wolfe, eager to show that the world he is depicting in The Painted Word is utterly fraudulent, must make everyone and everything in it a swindle. Thus, in his attempt to show the absurdity of much contemporary art criticism, he undermines entirely the relation of criticism to creation. Thus, in From Bauhaus to Our House, in his attempt to show that Walter Gropius and his European colleagues were Utopian totalitarians, he all but asserts that all modern architecture is a hoax put over on Americans with a cultural inferiority complex. Throwing out the baby with the bathwater, along with being a cliché, is an old story; but when Tom Wolfe gets done, as in these two books, he has also removed the plumbing.

Any work of art that can be understood," the line from the old Dada manifesto had it, "is the product of a journalist." It may well be that Wolfe's simplifications in The Painted Word and From Bauhaus to Our House are owing to his own training in journalism. Splendidly observant, intellectually alert, learned even (Dr. Wolfe, I presume), Tom Wolfe is an immensely entertaining writer, but he does seem to work almost exclusively in primary colors. Fine shading is not his specialty. His is not what one thinks of as a finely graded mind; the style he has developed is ill-suited to fine gradations. On the bloody, three-dot, italic contrary.

Which is not to say that, as a writer, Tom Wolfe is without subtlety. He is extremely subtle, but on one topic chiefly: status. Wolfe has written on an impressive variety of subjects and on an astonishing range of characters — I consider the range between Leonard Bernstein and Chuck Yeager astonishing — but whatever the subject, whoever the character, the real story for Wolfe is status: who stands where on the rubber ladder. A foxy sort of hedgehog, Wolfe has written about everything and yet always about the same thing. In his pages, talent, money, audacity, all are measured by, and are rewarded with, status. Preoccupied with status though Wolfe is, he has not thus far in his career seemed himself snobbish. (Freud, after all, was not a sex fiend, nor Marx a miser.) Wolfe simply believes — or so, on the basis of his writing, I gather that he believes — that it is status that makes the world go round.

Certainly, Wolfe sees status dominating literary life. Literary status, in his view, works through literary forms, or genres, and in his introduction to The New Journalism he mapped out a literary class structure with novelists at the top ("the occasional playwright or poet might be up there, too, but mainly it was the novelists"), the middle class occupied by the literary essayists and certain authoritative critics, with the journalists down in the low-rent district. "When we talk about the 'rise' or 'death' of literary genres," he went on to say, "we are talking about status, mainly." (I happen to think the subject is much more complicated than that, mainly, but this is no place for an essay-length footnote to prove it.) As Wolfe then (in 1973) saw it, "the novel no longer has the supreme status it enjoyed for ninety years (1875-1965), but neither has the New Journalism won it for itself. In some quarters the contempt for it is boundless . . . even breathtaking ..." Today the word "contempt" in that last sentence would have to be changed to "apathy."

Tom Wolfe has always liked to play being Jeane Dixon, shooting off predictions about forthcoming trends, and in his introduction to The New Journalism he predicted a new life for the novel, or, more precisely, a life for a new kind of novel:

I think there is a tremendous future for a sort of novel that will be called the journalistic novel or perhaps documentary novel, novels of intense social realism based upon the same painstaking reporting that goes into the New Journalism. I see no reason why novelists who look down on Arthur Hailey's work couldn't do the same sort of reporting and research he does — and write it better, if they're able. There are certain areas of life that journalism still cannot move into easily, particularly for reasons of invasion of privacy, and it is in this margin that the novel will be able to grow in the future.

Fourteen years later Wolfe has made this prediction come true by producing precisely such a novel himself. To put it Wolfe-ishly, The Bonfire of the Vanities is Tom Wolfe's bid to make it — now!. ... to break free from being a grubby journalist, however New and Glittering and Well Paid. . . and to become, are you ready for it, hey, give me a double (single-deck) ellipsis here…. Literature!

Not long after reading Tom Wolfe's novel, I came across a reference to an event of the kind from which it takes its title — The Bonfire of the Vanities — in Thomas Mann's Doctor Faustus. In describing the town of Kaiseraschern, in which the narrator and Adrian Leverkühn came of age, he, the narrator, remarks: "Rash it may be to say so, but here one could imagine strange things: as for instance a movement for a children's crusade might break out; a St. Vitus's dance; some wandering lunatic with communistic visions, preaching a bonfire of the vanities; miracles of the Cross, fantastic and mystical folk-movements — things like these, one felt, might easily come to pass." Savonarola, it will be recalled, beseeched the terrified citizenry of late fifteenth-century Florence to toss their vain personal ornaments, including books and paintings, into a symbolic fire — a bonfire of the vanities — that would purge their sins. Early in Tom Wolfe's novel, when he first describes his main character's sumptuous Park Avenue apartment, he remarks that it is a place of the kind "the mere thought of which ignites flames of greed and covetousness under people all over New York and, for that matter, all over the world." Right out of the gate, then, we are under advisement that symbolic flames will follow.

Which is not to say that, as a writer, Tom Wolfe is without subtlety. He is extremely subtle, but on one topic chiefly: status.

The Bonfire of the Vanities is an audacious book. Its ambition is grand and so is its scope, for it covers life at the high tables of Manhattan down to the lock-up at the Bronx County Courthouse. It is a hefty tome of 659 pages, which would make a fairly good bonfire of its own, and seems to be written in defiance of the notion that, if one wishes to make a major statement in our time, one had better make it short. It is audacious in yet another sense: it says things that no one else in our time has quite dared to say, at least not in print, not publicly. It posits that modern big-city life has become a jungle, full of danger and despair and disaster waiting to erupt. It further posits that there are men, some among them black men who are would-be leaders of their people, who profit handsomely from this arrangement. It has no regard for ethnic sensitivities, insofar as two of its most loathsome characters, both attorneys, are Jews, and makes the assumption that ethnic groups generally live among one another in a perpetual state of not very deeply suppressed animosity. Roughly midway through the novel, reference is made to three V.I.F.s. "'V.I.F.'s?' asked Sherman. 'Very important Fags,' said Judy, 'that's what everybody calls them.'" This, then, is not a novel that has set its sights on winning the B'nai Brith Human Relations Award.

Much of the negative press — in The Nation, New York, The New Republic (whose review carried the title "The Right-Wing Stuff") — that The Bonfire of the Vanities has received has been owing to its politics. These are strongly anti-Left, at least insofar as Wolfe attributes much of the serious mischief in contemporary urban life to radical hustlers and soft-hearted (also -headed) liberal culture of a kind unwilling to admit unpleasant facts about contemporary life. One such fact is that the New York City public school system is spiritually bankrupt, and its greatest victims are black and Hispanic kids. Of the students at the Colonel Jacob Ruppert High School in the Bronx, one Mr. Rifkind, a teacher with a minor role in the novel, remarks: "At Ruppert we use comparative terms, but outstanding isn't one of them. The range runs more from cooperative to life threatening." The same teacher says, "Written work? There hasn't been any written work at Ruppert High for fifteen years! Maybe twenty!" I would add that there hasn't been candor on such subjects, in our journalism or in our literature, for even longer.

Without an unblinkered view of reality, there can be no realism in literature. If one were to read the American fiction of the past few decades, one would be little likely to discover that large stretches of American cities are simply out of bounds to large segments of the population. Black or white, one can easily be killed in those streets. One can easily be killed, at least in spirit, in the media as well. One of the most terrifying moments in Wolfe's novel occurs as the members of the media are closing in on the main character, a successful bond broker named Sherman McCoy, who has been indicted for running over a black adolescent in the Bronx.

They closed in for the kill. And then they killed him.

He couldn't remember whether he had died while he was still standing in line outside, before the door to Central Booking opened, or while he was in the pens. But by the time he left the building and Killian [his lawyer] held his impromptu press conference on the steps, he had died and been reborn. In his new incarnation, the press was no longer an enemy and it was no longer out there. The press was now a condition, like lupus erythematosus or Wegener's granulomatosis. His entire central nervous system was now wired into the vast, incalculable circuit of radio and television and newspapers, and his body surged and burned and hummed with the energy of the press and the prurience of those it reached, which was everyone, from the closest neighbor to the most bored and distant outlander titillated for the moment by his disgrace.

Or, as Wolfe puts it in an earlier trope: "they were the maggots and the flies, and he was the dead beast they had found to crawl over and root into."

The Bonfire of the Vanities is about the wretched misadventures of Sherman McCoy (Buckley, St. Paul's, Yale), a man in his late thirties who lives in one of the best apartments in one of the best buildings on one of the best streets in the most important city in the world and who is earning only $20,000 shy of a million dollars a year and going broke. Sherman has a wife named Judy and a daughter named Campbell and a dachshund named Marshall and a southern mistress named Maria Ruskin, who is herself married to a rich, much older man, a Jew whose fortune is built on chartering flights for Arabs bound for Mecca. It is while driving Maria home from Kennedy Airport, in his Mercedes roadster (engine size, oddly, not noted), feeling masterful and atop the world ("There it [Manhattan] was, the Rome, the Paris, the London of the twentieth century, the city of ambition, the dense magnetic rock, the irresistible destination of all those who insist on being where things are happening — and he was among the victors!"), that Sherman misses the off-ramp to Manhattan and finds himself, beautiful woman beside him in a $48,000 car, in the Apache territory of the Bronx.

"The Bonfire of the Vanities" is a novel in which nearly every character searches for others down on whom he can look — and usually finds them.

Tom Wolfe's handling of this material is altogether adroit. Cutting back and forth between five or six major characters, never lingering overlong with any one of them, or with the numerous subsidiary characters in this Russian-length novel, bouncing from social class to social class, subject to subject, The Bonfire of the Vanities is neatly paced, without a longueur in the book. Whether an upper-class homosexual lawyer or a black drug dealer is talking, an English journalist or a Jewish cop, a maitre d' in a Manhattan Frog Pond restaurant or a lower-middle -class Greek bimbo, the dialogue in this novel always and everywhere feels right. The details are deft; a vast amount of information about the way (I won't say "we" but) some people live nowadays is dispensed. In sum, the book, as one thinks of them saying at editorial sales meetings, is a helluva read.

At this point, permit me to pose a question that I don't think will bore many people: How does a young man, not yet forty, without having a drug or gambling problem and with no one blackmailing him, manage to be going broke on an annual salary of $980,000? It isn't that difficult to spend more than $980,000 a year in current-day Manhattan, as Tom Wolfe demonstrates in perfectly persuasive financial detail. I shall not rehearse all the details here, but it may give some inkling of Mr. Sherman McCoy's problem to say that, for real-estate payments alone (loan repayments, mortgages, maintenance assessments, taxes) on a $2.6 million Park Avenue apartment and a house in Southampton, our boy is in for $368,000. Now toss in a few line items like $37,000 for restaurants and entertaining at home, $62,000 for servants (a nanny for the child, a cook and cleaning woman, a handyman for the place in Southampton), $65,000 for clothes and furniture, and a lousy $10,080 for parking two cars in Manhattan. You might think there is room for trimming things down here. $2.6 million might seem a bit high for a pad, for example, but Wolfe, most amusingly, shows how little in the way of quality in an apartment one gets these days for $1 million ("8 foot ceilings, a dining room but no library, an entry gallery the size of a closet, no fireplace, skimpy lumberyard moldings, if any, plasterboard walls that transmit whispers, and no private elevator stop"). It's a problem, no doubt about it.

But let us talk a bit further about clothes. The dandiacal Mr. Wolfe not only dresses his characters with care — that one would expect — but tells us the name brands of their clothes, the prices paid for them, and often the shops in which they were purchased. Thus we learn about a rubberized British riding mac "bought at Knoud on Madison Avenue"; a soft leather attaché case of the kind that "come from Mädler or T. Anthony on Park Avenue"; sport jackets that are bought at Huntsman, Savile Row; Shep Miller suspenders; New & Lingwood shoes (lots of these), at New & Lingwood, Jermyn Street, London. Ah, me, in the 1890s dandies wrote for the Yellow Book; now they use the Yellow Pages.

Clothes perhaps weigh in too heavily in Tom Wolfe's reckoning of character. Some of his details about them, it must be said, are very sharp. A down-on-his-uppers British journalist named Peter Fallow wears a once expensive blazer that is beginning to show serious wear on its lapels; an assistant district attorney named Larry Kramer wears Nike sneakers and carries his Johnston & Murphy brown dress shoes in an A&P bag on the subway; the lawyer who defends Sherman McCoy, a man named Thomas Killian, always dresses to the nines (make that the thirty-sixes), and he is one of the few characters in the book of whom Wolfe approves.

Is this sound novelistic practice? In having Larry Kramer carry his not very elegant shoes to work in an A&P bag, Wolfe is telling us, here is a dullish man, without flair or imagination, the reverse of a sport, essentially lower-middle class, a clod — all of which Kramer turns out to be, as well as being cheap, lecherous, sycophantic, self-deluded, and dishonest. Could he not, though, have been quite as dreary in, say, an Alden tassled version of a full-strap slip-on in imported aniline calfskin? How would Henry James have handled it? What did Gilbert Osmond, that great snob, wear in The Portrait of a Lady? All James says by way of description is: "He was dressed as a man dresses who takes little other trouble about it than to have no vulgar things." Henry James lets Osmond dress himself, or rather lets us dress him in our own minds, but then James is fishing in deeper waters.

Henry James was interested in moral drama. Tom Wolfe is here interested in the drama of social status, of which he ultimately morally disapproves. Yet his fascination with the drama of social status is at least as great as his disapproval. In Henry James every decision has its moral price; in Tom Wolfe every piece of furniture has its retail price. In the drama of status, only one mode of thinking exists — that of comparison. Such a drama presents its players with a single problem — that of positioning themselves through their taste or wealth or political virtue or beauty or family standing. The Bonfire of the Vanities is a novel in which nearly every character searches for others down on whom he can look — and usually finds them. Take Larry Kramer, the assistant district attorney with the Johnston & Murphy shoes in the A&P bag. He and his wife, who has just had a baby, are living in an over-priced, jerry-built Manhattan apartment and have hired for a few weeks, at the rate of $525 per week, an English baby nurse, about whom Kramer feels rather edgy, until the nurse speaks out against "the colored," who don't know "how good they've got it in this country." The edge, with that remark, is off. Wolfe has Kramer and his wife think:

Thank God in heaven! What a relief! They could let their breaths out now. Miss Efficiency was a bigot. These days the thing about bigotry was, it was undignified. It was a sign of Low Rent origins, of inferior social status, of poor taste. So they were the superiors of their English baby nurse, after all. What a fucking relief.

"Everyone is striving for what is not worth the having," says Lord Steyne, in Vanity Fair, a novel to which The Bonfire of the Vanities has not infrequently been compared. Vanity Fair carries the subtitle A Novel Without A Hero and this, by and large, is true, too, of The Bonfire of the Vanities. Among the crucial differences is that in Thackeray's novel not everyone is a swine, as nearly everyone is in Wolfe's, and in Thackeray there is still an aristocracy worth imitating whereas in Wolfe such aristocracy as America has known has by the time of the novel all but crumbled. (One of the sub-themes of Wolfe's novel is the decay and decline of the WASP upper classes — and it is an important one.) In The Bonfire of the Vanities just about everyone has his own agenda, his own fantasies of money, power, sex, mastery, all issuing in greater status — which is to say, everyone has his own towering vanity. I cannot recall a generous emotion or sentiment in this entire novel; everyone in it is in business absolutely for himself.

"Vanity only sins," wrote Lord Lytton, "where it hurts the vanity of others." Much of the artfulness of Tom Wolfe's plot is owing to his skill at setting vanities clashing against one another. The horror of Sherman McCoy's fall is that his own vanity is chewed up by the vanity of a great many others: an alcoholic British journalist who sustains his career in the gutter press by sensationalizing McCoy's accident and trial; a corrupt black leader for whom McCoy's manslaughter case is a godsend; a Jewish district attorney up for re-election in a black and Hispanic district for whom a case like McCoy's is equated to bringing in the Great White Whale (accent on White); and so forth and so on. After the assistant district attorney Larry Kramer expends money, time, and great emotional energy on seductive strategy, finally making his move on a young woman he has fantasized about for months, we learn that she is in fact a bit of a tart, bored by his self-dramatizing and principally interested in popping into bed. When an older man in the company of a journalist has a deadly heart attack at La Boue d'Argent restaurant, his face falling into a plate of médallions de selle d'agneau Mikado, his companion, after the tumult and mess of removing the body from the restaurant, is presented with (you will pardon my French) l'addition, which, truth to tell, he hadn't counted on paying in the first place. Another night — afternoon, actually — in little ole New York.

"Who is ever missed in Vanity Fair?" asks Thackeray, and I fear something similar can be said about the characters in The Bonfire of the Vanities. However interestingly and accurately they are drawn — and they are drawn most interestingly and accurately — one does not long to hear more from them. Wolfe has been altogether too efficient at his job of demolition. (Look, the emperor has no fibula, navel, buttocks!) Wolfe puts Sherman McCoy through the full hell of the so-called criminal justice system, exposes him to the complete torture of the media, fries him in betrayal, boils him in shame, and yet, so devastatingly has he earlier drawn him as a miserable mindless snob, that the redemption Wolfe allows him at the novel's close seems unpersuasive, which is a milder way of saying aesthetically unsatisfying.

It is very hard to write a novel with no hero without, at the same time, one's readers knowing exactly what it is you believe in. The author of The Bonfire of the Vanities, sad to report, is for the first time not always above the snobberies he depicts in his own work. He is not above mocking (in an unplayful way) New York accents, or belittling dreary apartments, or comically degrading a man who buys his clothes "from the Linebacker Shop, for the stocky man, in Fresh Meadows." When Wolfe lets his own point of view peep through, it isn't always pleasant to behold. His hatred for the high and vacuous celebrity culture is undisguised; his Olympian amusement at the nouveau riche has long been known. But what is surprising in his novel is to find him looking down his nose, as in the examples cited here, at the lower-middle class, or (as Marx neglected to call them) the schleppoisie.

The lower-middle class, my guess is, repels the dandy in Wolfe. Anyone who has ever seen Tom Wolfe's drawings knows that the quality of revulsion runs high in him. His drawings, with their ungracefully aging couples out jogging, their balding and ungainly intellectuals, their hopelessly overweight men on the disco dance floor attempting to hang in there with the young, their overdressed New York women who are all crotch and bust and bottom — all these drawings register pure disgust on Wolfe's part. As a penman, so as a draughtsman, he has always mocked other people's vanities, and the past few decades have kept him in full employment.

The difference, ultimately, between the novelist and the journalist is that the real subject of the novel is the truths of the human heart. Our greatest novelists have always known this, and now the greatest journalist of our time, who has missed this essential point, has proven it yet again.

But does Wolfe believe in anything more than the need to skewer other people's vanities? "It is only to vain men that all is vanity," Joseph Conrad wrote in his story "Prince Roman," "and all is deception only to those who have never been sincere with themselves." In what does Tom Wolfe believe? Is there anything he admires? On the evidence of this novel, and of his earlier writings, I should say two things: command of craft and courage. Thomas Killian, the attorney in the novel who is good at what he does, is one of the book's few characters who is not mocked. Neither, finally, is another character, a judge named Myron Kovitsky, who in the social jungle of the Bronx is absolutely fearless and takes crap from no one. When craft and courage combine, as they do in test pilots and astronauts, stock-car racers and navy fighter pilots, Wolfe drops his guard and writes in open, uncritical adulation. It was Ken Kesey's crazy courage that in large part attracted Wolfe in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. In The Bonfire of the Vanities, Sherman McCoy is redeemed when he finds the courage — physical as well as spiritual — to face down his attackers. (Admiration for physical courage traditionally runs strong in southern men.) If one views the world as essentially a fraudulent place, a vanity fair, then perhaps all that one can trust are courage and craft. And yet this seems, for a novelist, oddly limiting.

To his journalism, Tom Wolfe brought the techniques of the novelist, and now to his novel he brings the temperament of the journalist. The latter arrangement turns out not to work quite so well as did the former. The journalist acquires his information in order to choose sides; the novelist acquires his information not for the purpose of choosing sides but for exploring human character. The Bonfire of the Vanities, impressive in so many ways, is nonetheless an almost paradigmatic case of the way that the journalistic mind works. The characters in the book are all fictitious but none, so far as the author is concerned, is ever really innocent, or capable of surprising, or of teaching us anything about life.

The best qualities of The Bonfire of the Vanities are, at their core, journalistic ones: reams of fascinating information about the way people live, the way institutions work, and the way people can be ground down by both institutions and their own empty vanities. Novelists who ignore making use of such material by considering it merely journalistic are very great fools, but the serious novel, while including all this, goes beyond it. The difference, ultimately, between the novelist and the journalist is that the real subject of the novel is the truths of the human heart. Our greatest novelists have always known this, and now the greatest journalist of our time, who has missed this essential point, has proven it yet again.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Joseph Epstein. "Tom Wolfe's Vanities." The New Criterion (February, 1988).

Joseph Epstein. "Tom Wolfe's Vanities." The New Criterion (February, 1988).

Reprinted with permission of the author, Joseph Epstein and The New Criterion.

The Author

Joseph Epstein is a Chicagoan essayist, short story writer, and editor, best known as a former editor of the Phi Beta Kappa Society's American Scholar magazine and for his recent essay collection. He is the author of 22 books, among them Gossip: The Untrivial Pursuit, Snobbery: The American Version, Friendship: An Expose, and Alexis de Tocqueville: Democracy's Guide. In addition he is the author of 10 collections of essays and three of stories. He has written for the New Yorker, the Atlantic, Harper's, Commentary and many other magazines. He lives in Chicago, where he was born and has lived most of his life.

Joseph Epstein is a Chicagoan essayist, short story writer, and editor, best known as a former editor of the Phi Beta Kappa Society's American Scholar magazine and for his recent essay collection. He is the author of 22 books, among them Gossip: The Untrivial Pursuit, Snobbery: The American Version, Friendship: An Expose, and Alexis de Tocqueville: Democracy's Guide. In addition he is the author of 10 collections of essays and three of stories. He has written for the New Yorker, the Atlantic, Harper's, Commentary and many other magazines. He lives in Chicago, where he was born and has lived most of his life.