The Lnklings: The Other Oxford Movement

- WALTER HOOPER

The Oxford Movement began in 1833 under the leadership of John Keble, E.B.Pusey and John Henry Newman. Another movement which began in Oxford a century later and which has given us shelves of great books is that of The Inklings.

|

|

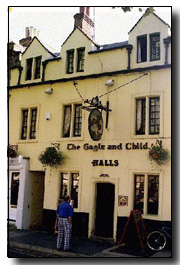

Bird and Baby pub

|

The Oxford Movement began in 1833 under the leadership of John Keble, E.B.Pusey and John Henry Newman. These churchmen had in mind a return of the Anglican Communion to a 'Catholic' Church faithful to the Early Fathers and free of undue influence from the States. It reached its climax in 1845 with Newman's conversion to Catholicism.

Another movement which began in Oxford a century later and which has given us shelves of great books is that of The Inklings. This group of Christian friends, most of whom taught at Oxford University, included C.S.Lewis, J.R.R.Tolkien, and Owen Barfield. They met weekly in Lewis's rooms in Magdalen College to talk, drink, and read aloud whatever any of them was writing. They gathered as well on Tuesday mornings over beer and pipes in the Eagle and Child pub, or 'Bird and Baby' as it is known. Visitors to Oxford can usually find a seat in the snug little back room of the 'Bird and Baby' where photographs and other mementoes of The Inklings are displayed. When you are settled with a drink, you'll probably ask 'Why did they call themselves "Inklings"?' 'How did it all begin? The first question was answered by Tolkien who explained that they were 'people with vague or half-formed intimations and ideas plus those who dabble in ink.'

They began with C.S.Lewis and his passion for hearing things read aloud. The first to share this with him was Owen Barfield. They met at Oxford in 1919 when both were undergraduates.

Lewis loved 'rational opposition' and Barfield supplied plenty of this. Besides sharing the same interests, Lewis wrote in Surprised by Joy, Barfield 'approaching them all at a different angle.' 'When you set out to correct his heresies,' said Lewis, 'you find he forsooth has decided to correct yours! And then you go at it, hammer and tongs, far into the night...out of this perpetual dogfight a community of mind and a deep affection emerge.' Barfield compared arguing with Lewis to 'wielding a peashooter against a howitzer'. It must be understood that 'rational opposition' is not quarreling. 'We were always,' said Barfield, 'arguing for truth not for victory, and arguing for truth, not for comfort.' Before he moved to London in 1930 to work as a solicitor, Barfield published Poetic Diction (1928), a work that was to have a profound influence on the other Inklings.

Lewis's next great friend was J.R.R.Tolkien. They met in 1926, each having joined the English faculty of Oxford University the year before, Lewis as Fellow of English at Magdalen College and Tolkien as Professor of Anglo-Saxon. 'At my first coming into the world,' Lewis said in Surprised by Joy, 'I had been (implicitly) warned never to trust a Papist, and at my first coming into the English Faculty (explicitly) never to trust a philologist. Tolkien was both.' The friendship nevertheless grew quickly, and soon Tolkien was going to Lewis's college rooms on Monday mornings where he read aloud some of The Silmarillion, early stories about his huge mythological world of 'Middle-Earth'.

It was Lewis's grandfathers who warned him against the Papists, and it is interesting to imagine what they would have thought of the debt their grandson would one day owe this particular Catholic. Lewis became an atheist when he was fourteen as a result of finding that all teachers and editors of the Classics took it for granted that the beliefs of the Pagans were 'a mere farrago of nonsense'. As they did not attempt to show how Christianity fulfilled Paganism or how Paganism prefigured Christianity, Lewis concluded that Christianity was equally nonsensical. Then came an evening in Magdalen College, 19 September 1931, that was to be the most momentous of his life. Lewis invited Tolkien and Hugo Dyson, a teacher at Reading University, to dine. By the time Tolkien left Magdalen at 3 a.m. Lewis understood the relationship between Christianity and Paganism. 'What Dyson and Tolkien showed me,' he wrote to Arthur Greeves on 18 October 1931, 'was that the idea of a dying and reviving god...moved me provided I met it anywhere except in the gospels...Now the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference that it really happened: and one must be content to accept it in the same way, remembering that it is God's myth where the others are men's myths: i.e. the Pagan stories are God expressing Himself through the minds of poets, using such images as He found there, while Christianity is God expressing Himself through what we call "real things"...namely, the actual incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection.' From this point on Lewis became a muscular defender of those 'Real Things.'

About this same time an undergraduate at University College, Edward Tangye Lean, formed a club actually called 'The Inklings'. Its members met for the very purpose of reading aloud unpublished compositions, and Lewis and Tolkien were invited to join. The club died when Lean took his degree and left Oxford in 1933, and Lewis and Tolkien then transferred its name to their group in Magdalen.

The foundations of The Inklings were now in place. Lewis's brother, Warnie, attended the occasional meeting when he was home from the Army, and they were often joined by Barfield and Hugo Dyson. Then on 4 February 1933 Lewis wrote excitedly to Arthur Greeves: 'Since term began I have had a delightful time reading a children's story which Tolkien has just written.' It was The Hobbit (1937), the first work by an Inkling to become a classic. From there Lewis and Tolkien went on to plan a joint project. They were dissatisfied with much of what they found in stories, and Lewis suggested that they each write one of their own. They had in mind stories that were 'mythopoeic' having the quality of Myth but disguised as thrillers. Tolkien's wrote 'The Lost Road,' the story of a journey back through time.

Lewis saw it as an opportunity to put into effect one the things that was to be a hallmark of his writing. It is a 'Supposal' suppose there are rational creatures on other planets that are unfallen? Suppose we meet them? 'I like the whole interplanetary idea,' he said, 'as a mythology and simply wished to conquer for my own (Christian) point of view what has always hitherto been used by the opposite side.' The result was his novel, Out of the Silent Planet (1938), in which the adventurers from Earth discover on Malacandra (Mars) three races of beings who have never Fallen, and are not in need of redemption because they are obedient to Maleldil (God). When some of his readers failed to see what he was 'getting at', he concluded that 'any amount of theology can now be smuggled into people's minds under cover of romance without their knowing it.' Some years later The Inklings were treated to another of Lewis's 'supposals' in the Chronicles of Narnia. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was, he said, an answer to the question, 'Supposing there was a world like Narnia, and supposing, like ours, it needed redemption, let us imagine what sort of Incarnation and Passion and Resurrection Christ would have there.'

While Lewis was still writing Out of the Silent Planet, Tolkien began his masterpiece, The Lord of the Rings, which was read and discussed during many meetings of The Inklings. This work cannot be separated from one of Tolkien most important literary theories that of 'sub-creation' which he wrote about in his essay 'On Fairy Stories.' According to Tolkien, while Man was disgraced by the Fall and for a long time estranged from God, he is not wholly lost or changed from his original nature. He retains the likeness of his Maker. Man shows that he is made in the image and likeness of the Maker when, acting in a 'derivative mode', he writes stories which reflect the eternal Beauty and Wisdom. Imagination is 'the power of giving to ideal creations the inner consistency of reality.' When Man draws things from the Primary World and creates a Secondary World he is acting as a 'sub-creator'. His sub-creations may have several effects. Man needs to be freed from the drab blur of triteness, fimilarity and possessiveness which impair his sight, and such stories help him recover 'a clear view' of the Creation. Another effect is the 'Consolation of the Happy Ending' or Eucatastrope. Such stories do not deny the existence of sorrow and failure, but they provide 'a sudden glimpse of the underlying reality or truth'. After all, the Gospel or Evangelium contains 'a story of a larger kind which embraces all the essence of fairy stories'. In God's kingdom we must not imagine that the presence of the greatest depresses the small. The Evangelium has not destroyed stories, but hallowed them, especially those with the 'happy ending'.

The Second World War caused a huge upheaval in Oxford. Most of the Inklings had served in the First War but they could not be sure they would be left alone this time. Warnie Lewis was recalled to active service in 1939, and now, in retrospect, it is clear that the war years were The Inklings's golden age. The many new members who joined during these years included: Lord David Cecil, lecturer in English at New College; Nevill Coghill, English tutor at Exeter College; James Dundas-Grant, Commander of the Oxford University Naval Division; Adam Fox, Dean of Divinity at Magdalen; Colin Hardie, Classical Tutor at Magdalen; R.E. 'Humphrey' Havard, Lewis's doctor; R.B.McCallum of Pembroke College; Father Gervase Mathew OP of Blackfriars, C.E.Stevens, historian at Magdalen; Charles Wrenn, Lecturer in English Language; Christopher Tolkien (son of JRRT) and John Wain, both students at the time. Of the new members perhaps the one who had the greatest influence on Lewis was Charles Williams, an employee of Oxford University Press, who was evacuated with the Press to Oxford. Lewis was a fervent admirer of Williams's 'theological thrillers' beginning with The Place of the Lion. Other friends such as George Sayer and Roger Lancelyn Green dropped in when they were visiting Oxford.

It was rare for all these men to be at every meeting, and some who could not get to the evening gatherings were present at 'The Bird and Baby' on Tuesday mornings. The Thursday evening meetings in Lewis's rooms began about 9 p.m., and describing them in Sprightly Running John Wain said: 'I can see the room so clearly now, the electric fire pumping heat into the dank air, the faded screen that broke some of the keener draughts, the enamel beer-jug on the table, the well-worn sofa and armchairs, and the men drifting in...leaving overcoats and hats in any corner and coming over to warm their hands before finding a chair. There was no fixed etiquette, but the rudimentary honours would be done partly by Lewis and partly by his brother... Sometimes, when the less vital members of the circle were in a big majority the evening would fall flat; but the best of them were as good as anything I shall live to see.'

It was in this setting that, along with from lively talk about many things, and without an iota of self-consciouness about securing a place in history, Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings, C.S.Lewis's The Problem of Pain, The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, Charles Williams's All Hallow's Eve, and Warnie Lewis's The Splendid Century were along with other works by other members read and discussed. Those of us who did not enjoy the privilege of being there can at least imagine what it must have been like to read one's own work to such a friendly but formidable jury.

We must not think of The Inklings as anything like a 'mutual admiration society' or men hungry for professional advancement. They were, first and foremost, Christians, who had in common something that was far more important than their jobs or their other interests. Nowhere is this better put than in the definition Lewis gave of Friendship in The Four Loves: 'In this kind of love,' he said, 'Do you love me? means Do you see the same truth? or at least, 'Do you care about the same truth?' If Cardinal Newman had been alive at the time, this was the club in which he would have felt at home.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Walter Hooper. "The Inklings: The Other Oxford Movement" Catholic World Report (June 1997).

This article is reprinted with permission from Catholic World Report an international news monthly. Catholic World Report also publishes Catholic World News.

The Author

Walter Hooper was the secretary of C.S. Lewis and today works for the Lewis estate. He lives in Oxford. The above article first appeared in the Second Spring section of Catholic World Report.

Copyright © 2002 Walter Hooper