The Christian Response to Atheism: Dostoevsky

- RALPH MCINERNY

In his novels, Dostoevsky brings out the truth that those who "kill" God also kill man and that man without God cannot remain free.

|

|

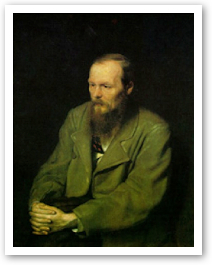

Fedor Dostoevsky

1821-1881 |

The principal representative chosen by de Lubac to offer the Christian response to modern atheism is the novelist, Fedor Dostoevsky. In simple but compelling terms, the nineteenth-century Russian author explains the situation of the West: The West has lost Christ and that is why it is dying; that is the only reason. The one basic choice placed before modern man is that between the man-god of the atheists and the God-man of Christian revelation. Dostoevsky had faced that choice himself and made it in favor of Christ and the faith of the Church. He saw the same choice placed before every man.

Many atheists pass across the pages of Dostoevsky's novels. Through them, Dostoevsky shows in dramatic fashion that, without God, man has nothing but falsehood and inevitably becomes an enemy to himself, and ends by organizing the world against himself. He shows the disaster coming upon man as a result of those revolutionary ideals which are the legacy of Western liberalism and its project of eliminating God and secularizing society. No matter how valid is this or that element in the secularist critique of society, Dostoevsky sees the truth that those who kill God also kill man. He also saw that man without God cannot remain free.

As the curtain is about to fall on the drama played out in the pages of de Lubac's work, we might ask if he sees any hope. Since this book is a deeply Christian meditation on the Christian situation, the answer is necessarily affirmative. De Lubac allows Dostoevsky to respond for him.

The first sign of hope is in the faith of those Christians who have continued to believe from the heart. Many of these are unlearned and poor. For example, a character in one of his novels meets a young peasant woman with a baby. When the baby smiles for the first time, the woman makes the Sign of the Cross. When asked why she made this sign, the woman answers: ``All the joy that a mother feels when she sees her child smiling for the first time... God feels every time He sees... a sinner praying to him from the bottom of his heart. From this event, Dostoevsky takes hope, seeing that the very heart of Christianity is expressed by a poor woman of the people. Such simple faith is the most compelling answer to today's atheism.

Another reason for hope is the power of the gospel itself. Dostoevsky does not despair of the gospel touching the heart, even of the atheist who thinks man has invented God. The key to reaching such a person is to announce the gospel from personal experience of the Church's faith, thus showing that faith is not just words. The Christian must speak of his meeting with Christ, telling what he has seen and speaking of eternity. This might touch the heart of the atheist, who being really more idolater than atheist, is searching for someone to worship. Through contact with true Christians who preach the gospel by their lives as well as by words, the atheist might be converted and enter into the spiritual world, the gate of which is guarded by the mystery of Christ.

Such a conversion occurs in Crime and Punishment, when Raskolnikov, converted in Siberia, opens the New Testament. This, says Dostoevsky, is the beginning of another story. For the meeting with Jesus Christ and with his Church always marks the beginning of a new era for every individual person and for society as a whole. In that encounter alone begins the other story, the drama of a true Christian humanism and the salvation of the world.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Gormley, Sister Joan. The Christian Response to Atheism: Dostoevsky The Fellowship of Catholic Scholars Newsletter 19, no. 3 (Summer 1996): 43-44. This article is an excerpt from a larger review of the book The Drama of Atheist Humanism by Henri de Lubac.

Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

The Author

Ralph McInerny, the Michael P. Grace Professor of Medieval Studies and professor of philosophy at Notre Dame, holds degrees from the St. Paul Seminary, University of Minnesota and Laval University. He has taught at the University of Notre Dame since 1955 and was the director of the Jacques Maritain Center from 1979 to 2006. He is author of two dozen scholarly books and many more scholarly essays, as well as numerous general interest works. He is expert in the work of Thomas Aquinas, Soren Kierkegaard, and Jacques Maritain, and has written and lectured extensively on ethics, philosophy of religion, and medieval philosophy. McInerny is editor of an acclaimed series of translations of Aquinas's commentaries; for many years, he directed Notre Dame's prestigious Medieval Institute. Ralph McInerny's writings include about 67 books, many of them mysteries, including Thomas Aquinas: Selected Writings, The Writings of Charles De Koninck: Volume 1, The Writings of Charles De Koninck: Volume Two, Restoring Nature: Essays Thomistic Philosophy & Theology, Relic Of Time, Dante and the Blessed Virgin, and Stained Glass.

Copyright © 1996 The Fellowship of Catholic Scholars Newsletter