Melodies Everlasting

- ANTHONY ESOLEN

For the first time in the history of the world, there was a reliable way to hand music along from one generation to the next.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

Necessity is the mother of invention, they say, but in the history of the Church it has rather been zeal and charity. If I am going to evangelize a pagan people who live partly by herding sheep and partly by killing their distant kin and taking their property, I will have to learn how to speak to them and how to teach them the doctrines of the Faith, and eventually that will mean bringing them into the world of books. So in one sense it was a necessity that the monks who traveled north to the German tribes had to find a way to adapt the Roman alphabet to the sounds of their languages, using combinations of letters that were utterly impossible to civilized speakers of Latin. Consider, just for Anglo Saxon, such "barbaric" ways of beginning a word as hl, hr, hw, wr, wl, and cn, not to mention new characters for such odd sounds as that of th in this and a in that and w in will. Why, so strange to the ear were the Slavic tongues, that Saints Cyril and Methodius had pretty much to invent a new alphabet altogether. They had to do these things, if they were to evangelize. But who if not Love himself had sent them among barbarians to begin with?

So they dealt with speaking and reading. But what about that exalted form of expression known as singing?

Where are the songs of yesteryear? Aye, where are they? The ancient Greeks and Romans had their sacred songs, and their love songs, and war songs, and drinking songs. The Old Testament is filled with songs, including that most ravishing Song of Songs, redolent of eastern spices and dropping with honey. Do we have these ancient songs? We have their words. We do not have the melodies. The "alphabet" of music hadn't been invented. Oh, there was a lot of musical theory, and even musical mathematics. There were the "modes" with their Greek names, and customs regarding the kinds of rhythm that were fit for each. But, in the end, to learn music was like learning to recite poetry, among people who have no letters. It was to hear and repeat, to hear and repeat.

Hippocrates famously said that the physician's art was long, and life was short. He might have said the same thing about getting by heart the chants of the Church.

Songs for the year, songs for the ages

They weren't just three or four, those chants of the Church. Consider all of the prayers for every Sunday and feast day in the year. Consider the special hymns for morning and evening, for the Eucharist, for the penitential seasons, for the dedication of a church, or for the burial of the dead. Consider the 150 psalms, which monks all across Europe would chant during a single week at the most. What can you do with all of those melodies?

"I can read this!" he gasped, running his finger along the staves and singing the verses softly. "I can read it, without a singing master!"

You had three choices. First, you could shrug and say that whatever they were singing at Saint Gall need have nothing to do with what they sang at Monte Cassino. Let everyone sing ad libidinem. What difference does it make? Why should God care? But that violates the spirit of the liturgy itself, which demands that we give God our best, as did that first good shepherd Abel, and not any old mildewed ear of corn, as did Cain. It also betrays the universality of the Church. It is deeply comforting — strengthening — to know that when you sing the Victimae paschali at Easter, you are joining your voice with men and women and children the world over, in a harmony of worship and word and melody.

The second choice is what had prevailed for centuries. You could take the trouble to learn every one of the melodies by heart, and to teach them to others exactly as you learned them. That meant that to be a cantor at a church, you had to study under a master for two or three years. The problem with this, besides the sheer excruciating labor, is that eventually people make mistakes, and original melodies can be corrupted or lost altogether. For, unlike poetry, the music of the chant was "horizontal," not divided into easily recognized portions, and not structured by regularly recurring devices such as rhyme or the strict meters of Greek and Latin verse. The music was subordinate to the words and their meaning, and so could most delightfully "wander" accordingly, all while remaining within the range of an ordinary human voice.

Then there was a third choice.

The Pope reads a song

"I've called you, Brother Guido," says an old man seated upon a chair of authority, "to witness for myself the admirable discovery you have made."

The monk approaches. He is unsteady on his feet. One summer in mosquito-ridden Rome has ruined his health. Besides, he has had his share of trials and disappointments.

"Holiness," says the monk, "my enemies have brought me no end of trouble. Envy is a worse plague than malaria, and you see what that has done to me."

"Have no fear, my son. Bring me your famous book."

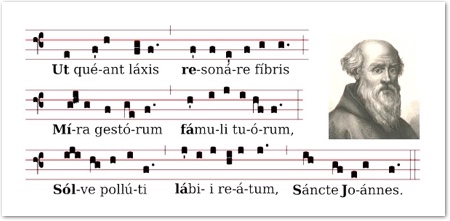

It is an antiphonary. Above the words in Latin, Pope John XIX saw what looked like a monastic grill, placed on its side: four parallel lines, extending from one end of a page to the other. One of the lines was marked in yellow. The monk said that that denoted the sound we call C. A red line marked F. A series of black marks — we now call them notes — were scattered not only along the lines but in the spaces between the lines. There were also some thin vertical lines to connect one note with another above it or below it. Sometimes one note was followed by another in the same position, but most of the time the music was ascending or descending. The trick was to find a way to fix how great the intervals were.

The monk now warmed to his task. "I've written that to learn music without a staff is like being down a well without a rope. Here is how the staff works." And he demonstrated to the pontiff what the notation meant, and how you could "see" the intervals we call a third or a fourth or a fifth.

We've all heard of the burst of meaning that came upon the blind and deaf girl, Helen Keller, when under the spout of a well-pump it suddenly came to her that the finger-signs her teacher tapped into her hand meant "water." I imagine that something like her astonishment struck Pope John.

"I can read this!" he gasped, running his finger along the staves and singing the verses softly. "I can read it, without a singing master!"

A magnificent invention

Brother Guido of Arezzo was soon welcomed back to the monastery whence he had been driven, and his invention spread across the continent. He wrote that the old method was like being a blind man who had to be led by hand. It was all right, he said, for boys who were just beginning, but frustrating for those who had progressed in the art. When he taught his boys the new method, some of them "could in three days sing a chant with ease, which under the old method they could have not have accomplished in many weeks."

Mozart once wrote that he would have given all his work for the fame of having composed the Gregorian Preface.

The method was more subtle than I can describe here. For one thing, Guido had to distinguish among different pitches of the same fundamental note, so that the boys singing soprano would have their A, and the men singing alto and tenor would have theirs. "Just as there are seven days" of creation, said Guido, so there are exactly seven "voices" or notes, designated by the familiar series of letters A, B, C, D, E, F, and G; the next note returning to A. He had to describe which notes were separated by a full tone, and which by a semi-tone; the "black keys" of Western music, so to speak, had not been invented yet (except for that wonderfully sweet B-flat). He described then how his method worked with the seven modes — two of which we would recognize as our major and minor scales.

Those are important details, but the main thing is that for the first time in the history of the world, there was a reliable way to hand music along from one generation to the next, or from people in Italy to people in Ireland at the edge of the world. Mozart once wrote that he would have given all his work for the fame of having composed the Gregorian Preface. He could never have uttered that pious exclamation — the Preface could never have endured, nor could he have composed his own work — had it not been for the zeal of the musical monk from Arezzo.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Anthony Esolen. "Melodies Everlasting." Magnificat (May, 2016): 230-234.

Anthony Esolen. "Melodies Everlasting." Magnificat (May, 2016): 230-234.

Join the worldwide Magnificat family by subscribing now: Your prayer life will never be the same!

To read Professor Esolen's work each month in Magnificat, along with daily Mass texts, other fine essays, art commentaries, meditations, and daily prayers inspired by the Liturgy of the Hours, visit www.magnificat.com to subscribe or to request a complimentary copy.

The Author

Anthony Esolen is writer-in-residence at Magdalen College of the Liberal Arts and serves on the Catholic Resource Education Center's advisory board. His newest book is "No Apologies: Why Civilization Depends on the Strength of Men." You can read his new Substack magazine at Word and Song, which in addition to free content will have podcasts and poetry readings for subscribers.

Copyright © 2016 Magnificat