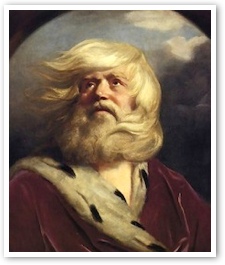

Shakespeare's King Lear

- MITCHELL KALPAKGIAN

Lear's failure to distinguish the florid rhetoric of flattery from just words of praise reveals also his inability to differentiate between quantity and quality.

|

Lear's loyal servant Kent advises the king to "see better," when Lear unjustly banishes his beloved daughter Cordelia for not flattering him with the bombast of her sisters proclaiming they love their father "Dearer than eyesight, space and liberty./ Beyond what can be valued, rich or rare,/ No less than life, with grace, health, beauty, honor." Before dividing his estate among his three daughters, Lear asks for professions of love: "Which of you shall we say doth love us most?" Lear does not see the distinction between the empty flattery of Goneril and Regan telling their father what he wishes to hear to gain the king's wealth and the just praise of Cordelia speaking simple, truthful words from a filial heart: "Unhappy that I am, I cannot heave/ My heart into my mouth. I love your Majesty/ According to my bond, nor more nor less." Lear also fails to discern the difference between words and deeds, appearance and reality.

Lear's failure to distinguish the florid rhetoric of flattery from just words of praise reveals also his inability to differentiate between quantity and quality. While the flattering daughters exaggerate their love with images of infinity ("Beyond what can be valued rich or rare"), Cordelia uses no such quantitative comparisons, instead using the language of justice and obligation to express her gratitude: "You have begot me, bred me, loved me. I/ Return those duties back as are right fit, /Obey you, love you, and most honor you." Lear fails to grasp the distinction between a woman loving a father and a woman loving her husband. Love and justice are not a matter of equality but proportion — what is "due" to a father is not the same as what is due to a husband. As Cordelia states, "Why have my sisters husbands if they say/ They love you all?" Because Lear intends to divide his land into three equal parts for each child, he determines his idea of justice with reference to a map with sections of one-third, assuming that equal portions of land have the same value.

Edmund, the illegitimate son of the Duke of Gloucester, also blurs distinctions — the difference between illegitimate children born out of wedlock in lust and legitimate children born in marriage from love. He sees no significant physical or mental differences between him and his half-brother Edgar: "When my dimensions are as well compact, / My mind as generous and my shape as true, /As honest madam's issue? Why brand they us with base? With baseness? Bastardy? Base, base?" Edmund regards the legal distinction between "legitimate" and "illegitimate" as arbitrary and illogical, a shallow convention with no basis in nature or reason. Deprived by this irrational custom and unjust law of his inheritance as the older son, Edmund curses the injustice of his lot and vows to gain his father's fortune by lies that accuse Edgar of treachery. Even though Edmund condemns the distinction as insignificant — a matter of only fourteen months' difference between him and his brother — and dismisses the difference as "the plague of custom," the elimination of this division leads to the same injustice and anarchy that follows from Lear's blindness. Without natural, logical distinctions and hierarchical order moral anarchy overthrows every principle of justice.

When Lear announces a visit to the castles of Goneril and Regan to whom, as he says, "I gave you all," they begrudge their father and king his retinue of one hundred servants and insist on only fifty, then twenty-five, and finally no more than ten or five. "What need one?" Regan asks as she resents the inconvenience and protests, "I am now from home and out of that provision/ Which shall be needful for your entertainment." She dethrones Lear from his status as monarch and reduces her father to an insignificant man. The ungrateful daughters regard the attendants as superfluous and burdensome rather than ceremonial and symbolic. They subordinate the venerable king and the aged father who bequeathed his entire fortune to them to a mere man deserving of no honor or respect. Offended by the insulting demands of his daughters, Lear refuses their debasing terms: instead he nobly exposes himself to the fury of a storm on the heath rather than stay with his daughters with no symbols of kingship or dignity. Without his servants and attendants Lear feels as undressed as a woman without elegant clothing and jewelry for formal occasions. In answer to Regan's question "What need one?" Lear explains that clothing, adornment, refinement, and formality distinguish man from animals and confer humanity.

Man rises above animals only when he observes all those amenities, manners, and morals that distinguish between honorable and dishonorable, noble and base, dignified and brutish, grateful and ungrateful, and sacrificing and selfish.

Man, unlike animals, wears clothing to announce his worth. Women do not merely wear work clothes but beautify themselves with elegant fashion, tasteful clothing, and beautiful jewelry. As Lear explains, "Allow not nature more than nature needs,/ Man's life's cheap as beasts./ Thou art a lady./ If only to go warm were gorgeous,/ Why, nature needs not what thou gorgeous wear'st/ Which scarcely keeps thee warm." Without titles, servants, clothing, beauty, gracious manners, and symbols of honor, man reduces himself to a paltry creature indistinguishable from animals and resembles the "poor, bare forked animal" that Lear sees when he finds Edgar dressed in rags and disguised as poor Tom of Bedlam.

During the raging storm when Lear feels impoverished and rejected, he ponders the question of whether or not man differs from animals. He invokes Nature to curse his ungrateful daughters and "dry up in them the organs of increase" because they return evil for good. He implores Nature to stop all human procreation that receives love but never gives it: "Strike flat the thick rotundity of the world! / Crack nature's molds, all germens spill at once/ That make ingrateful man." In witnessing the hardheartedness of his daughters, Lear sees no difference between fathering children in marriage with the love that gives "all" and animals reproducing by instinct: "Let copulation thrive, for Gloucester's bastard son/ Was kinder to his father than my daughters/ Got 'tween the lawful sheets." Man rises above animals only when he observes all those amenities, manners, and morals that distinguish between honorable and dishonorable, noble and base, dignified and brutish, grateful and ungrateful, and sacrificing and selfish. When man disregards hierarchical differences and logical distinctions, he unleashes all the lawless violence that Lear suffers in the fury of the storm as he fulminates, "Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks! Rage! Blow!/ You cataracts and hurricanes, spout/ Till you have drenched our steeples, drowned the cocks!"

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Mitchell A. Kalpakgian. "Shakespeare's King Lear." Crisis Magazine (August 27, 2013).

Reprinted with permission of Crisis Magazine.

Crisis Magazine is an educational apostolate that uses media and technology to bring the genius of Catholicism to business, politics, culture, and family life. Our approach is oriented toward the practical solutions our faith offers — in other words, actionable Catholicism.

The Author

Mitchell A. Kalpakgian was Professor of English at Simpson College (Iowa) for 31 years. During his academic career, Dr. Kalpakgian received many academic honors, among them the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Seminar Fellowship (Brown University, 1981); the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship (University of Kansas, 1985); and an award from the National Endowment for the Humanities Institute on Children's Literature. He is the author of The Marvelous in Fielding's Novels and The Mysteries of Life in Children's Literature. His favorite activities include writing, long distance running, and coaching soccer.Copyright © 2013 Crisis Magazine

Mitchell A. Kalpakgian was Professor of English at Simpson College (Iowa) for 31 years. During his academic career, Dr. Kalpakgian received many academic honors, among them the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Seminar Fellowship (Brown University, 1981); the Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship (University of Kansas, 1985); and an award from the National Endowment for the Humanities Institute on Children's Literature. He is the author of The Marvelous in Fielding's Novels and The Mysteries of Life in Children's Literature. His favorite activities include writing, long distance running, and coaching soccer.Copyright © 2013 Crisis Magazine