Fire in Our Darkness

- MICHAEL O'BRIEN

Michael O'Brien explores what is necessary for the Christian art of today to be true to its subject. In modern times, the lives of two religious artists, Georges Rouault (1871-1958) and William Kurelek (1927-1977), have left us markers.

|

Michael

Obrien |

On

Mount Horeb, place of encounter, the Lord communicates his presence to mankind

in symbolic form. He is a flame of fire blazing in the middle of a bush. And Moses,

so very human, goes forward to look, to encounter, to possess if he can what he

does not yet understand. Moses, Moses, says the Lord, Come no nearer. Take

off your shoes for the place on which you stand is holy ground. The light of

truth, the warmth of love are no less a flame in our own day, and like Moses we

too live and move and have our being in mystery. We are drawn by its fire and

repelled by its demands.

The mind of the modern secular age is no less a symbolic one than that of primitive man. If anything, we are a generation more saturated in images than any other in history. Perhaps this is the reason for our apathy, for now all experiences can come to us mechanically by television. It is no longer necessary to quest the secret fire of truth hidden within the mysterious events which shape us. It will all be brought to us painlessly in living colour. Our senses are being glutted directly or vicariously, and we seem to have no recourse but to recoil. Consequently, it takes more and more shock effect to touch us. Within our cities the unending roar of a thousand conflicting ideologies and advertisements compete for our souls. The entire world seems to be talking at fever pitch and there are few who remove their shoes to sit and listen at the feet of mystery. Above us all hangs the unholy fire of nuclear war. Unless we rediscover silence we shall be consumed by this violence on one hand or apathy on the other. Only in silence is it possible to understand how deafened we have become by the world's roar, its fears, its drives. Only in silence can we hear the cry of our own thirst, and only there will we begin to open our eyes upon a tree burning, unconsumed.

A warfare is presently under way in society. As Etienne Gilson says, it is no less than the mind of Antichrist we are engaging in battle. In the culture of the Western world we are witnessing the sterilization of the visual arts to a degree unprecedented in civilization. The art of our times is already despiritualized; now it is becoming dehumanized as well, as life itself is dehumanized. In the art galleries one finds works of technical brilliance, but the human theme, which defines us to ourselves, and the sacred theme, which calls us beyond ourselves, have all but disappeared. God is dead! has now come, as it must, to an equally ominous theme: Man, too, is dead. Consider a recent exhibition of sculpture at a major gallery in Ottawa. The artist offered us images of darkness, dismemberment of human beings, rape, and various forms of murder. Unquestionably one of the most brilliant portrayals of technique I have ever seen, it was a celebration of evil.

In fascist and Marxist regimes the true art of the people is underground. Publicly one sees only pseudo-religious symbols used for political purposes. The new icons are pictures of Marx, Lenin, and Chernenko. The great May Day parades are substitute religious processions. But the gospel of socialist realism in Soviet art does not even convince the party faithful. The virility of the samizdat press and the tenacity of the painters in Russia witness to how the creative impulse goes hand in hand with a yearning for freedom. In the West we are in danger of losing our souls to a far subtler tyranny. The enemy here is less visible and less willfully destructive. Yet violence and despair in our society speak of a people losing its identity and its awareness of the sacred. The decline of culture is alarming, for our culture most clearly reveals us to ourselves and to the world. Grants will not pump life back when the spirit has fled.

The art of the Church has been for millennia a principal shaper of the Christian sense of reality, but we are now at the end of an historical cul-de-sac in the arts. The Renaissance began a convulsion in Christendom. Man's understanding of his position in the order of creation was radically shaken. In a climate of liberal materialism new emphasis was given to his dignity, yet increasingly he was to search for his sense of self apart from the identity given him by Christianity. His personal worth resided no longer on the indwelling image of God, but in his mastery of commerce, ideas, and the arts, not least of which were the arts of politics and war. While raising civilization to new heights, the rebirth sowed the seeds of its own disintegration, for it initiated a divorce of the human and the divine. Painting clearly reflected this. Botticelli's madonnas, for instance, are indistinguishable from his Venus born naked from the sea. Even the best and most religious creators of the time were marked by a confusion of vision. Leonardo's John the Baptist is no voice crying out in the wilderness but a palace coquette in Christian costume. To dispense with the growth which the Renaissance gave us would be an error, but we must see that it injected a concept of man-as the-measure which has spread far and wide. And today we know that mere humanism inevitably degenerates into systems of dehumanization.

The Protestant Reformation brought further ambivalence to the question of art. Lutheranism tended to ignore it as a problem area where there had been abuses, yet permitted the fine portraiture of Luther and other leaders of the Reformation by men such as Lucas Cranach. Calvin, for whom the prime symbol of faith was The Word, condemned Catholic art outright, as idolatry. In an attempt to keep the faithful and win back the lapsed, the art of the Church became preoccupied with theatrical effects, making up in flamboyance what it lacked in depth. Despite its good intentions and even its real if limited qualities, it is clear that sacred art had been deflected from its true purposes: ministry and prophecy. Though this vocation had never been well defined and never perfectly lived, it had been operating instinctively almost from the beginning. The first Christians, scratching little crosses, doves, and Roman good shepherds on the walls of the catacombs, were lifting up signs of light in a darkening world. By the time of the Baroque era they had evolved to the outer limits of the real. The overwhelming messages to the senses began to drown the spiritual truth they were intended to portray. The shame and the pain of the artist in the midst of this turmoil turned him increasingly to secular themes. The princes and bankers were glad to give him a new home. Most successful artists still find their home, not in the Church, but in the boardrooms of corporations, the new princes.

The death of El Greco (1541-1614) in Spain ended the great age of sacred art. Since that time there has been only a small handful of significant religious artists. For the most part they suffered intensely and sacrificed much in order to paint religious imagery, achieving only a fraction of what they might have, had they been understood and supported by the Christian community. They were rare exceptions in a world of sacred art which had become a near-vacuum and would remain so from that time onward. Into the gap poured commercialism. Recognizing a need, the dealers and manufacturers rushed in to take up the call, concerned not with truth but with profit. Consequently, they flooded the market with a vast array of cheap, hastily produced, utterly shallow works appealing to the faithful on the lowest level of the emotional life, the maudlin. Where no real nourishment is provided, hunger will lead to junk-food.

Thirty years ago the Holy Office sent a series of directives to all Catholic churches throughout the world. Its Instructions to the Bishops on Sacred Art called for the removal of any images contrary to the holiness of the House of God and severely forbade second rate and stereotyped statues and effigies to be multiplied and absurdly exposed to veneration. Because good taste and sound judgement in matters of art are highly debatable, the Instructions have been largely ignored. The faithful had grown attached to these images; understandably so, because it is all they have had for a hundred years, especially in North America. Most Church art is still produced by factories, not created by a sense of mission or desire to incarnate the unseen reality. Only the artist transfigured in faith and master of his medium can accomplish this. Father P. Raymond Regamy, in Religious Art in the Twentieth Century, says, Nazi art, the socialist realism of the U.S.S.R., and the art that we normally find in churches are the three most dreadful manifestations of art that our century has witnessed. There is a harsh truth here. Who knows how many have rejected religion from a subconscious revulsion to paintings of Christ they have absorbed since childhood. An effeminate Jesus and saccharin madonna may appeal at one level of a starved emotional life, but they do not reach deeper to liberate and heal. The face of God must be portrayed in Christ as mercy and truth combined. Unless it is so, religious imagery will be a closed door inhibiting our growth in the Kingdom. Bad art has the power to deform a people just as good art generates new reflection, growth, vision, and hope.

As the creation of a human life demands everything of the mother-creator, so too the artist dies and is reborn again in every true act of making. It would be a narcissistic and ultimately self-defeating journey if it were made merely to increase a hoard of private treasure. But invariably where there is vision the artist has understood that his hard-won victories are gifts to be shared with the rest of humanity, fire carried back from the unknown country of his quest. The artist is all idealist, and for him the ideal is the real, capable of transforming his world into what it should be. For Western man it is difficult to grasp this curious vocation. He misreads art as decoration, entertainment, or a tool for imparting information. Corporate-industrial man has succeeded in alienating himself from the healing rhythms of nature, the wisdom of suffering embraced, the goodness of fertility and birth; his inability to respond to art is consistent with this. His light and power burn day and night, defeating the terrors of cave and womb, consequently prohibiting the birth of an authentic vision which can only occur while wrestling, like Jacob and the angel, in the dark. The artist who enters this combat may be, like Jacob, both wounded and victorious, discovering his new name, his identity in God. As he struggles to remain faithful during periods of emptiness and temptation he will gradually be transfigured. The transformations necessary for fulness of life will cost no less than everything. The person of prayer, the mystic, the healer, the prophet all know this. The artist will learn it too as he turns again and again towards the unknown. Like Prometheus, he will learn that fire stolen from the gods is deadly, but that fire received from the Father-Creator, as gift, is life.

On Mount Tabor, traditional site of the Transfiguration, Peter, James, and John were shocked witnesses to a radiant outburst of light. It was a moment of revelation, and as Peter chattered excitedly about tents, a bright cloud hovered and the Word boomed: This is my beloved Son; listen to him. The disciples, falling on their faces, were overcome with fear. In the Eastern Church the ancient spiritual discipline of icon-painting was worked out in such fear and trembling. The novice icon-painter spent many years praying, studying and working under a master, and no matter how excellent the technical facility of his images they were not thought to be true icons, nor was the novice an icon-painter. Only when the master felt that he was spiritually ready did he paint his first icon. By tradition this was an image of the Transfiguration, signifying that through his life and work he was to participate in the transfiguration of humanity. The master-disciple covenant has all but disappeared since the Renaissance. The last vestiges of the relationship can be found in teacher-student contracts where techniques and some philosophy of art are imparted. Certainly, technical excellence is indispensable and must be continually refined for the vision to be released. But in an age where technique has run rampant and vision become rarer we must wonder if an essential element has been lost.

In pre-revolutionary Russia entire villages and monasteries were devoted to the vocation of icon-painting; the gift was carefully handed down from generation to generation. This tradition is being renewed, mostly in religious communities here and there in the Western world. But the gifted layperson will not be blessed with the security and spiritual milieu of a community. Called to be a John the Baptist crying out in the wilderness, he is too often left to feel like Ishmael, weeping and abandoned in the desert. One solution to the problem may be rediscovery of the master-disciple covenant. There are still masters, a few men and women, who by sheer grit and a large measure of providence have emerged whole from the crucible of contemporary culture. But they are people who have not made their home in society. They exist on the periphery of what is called normal existence in the twentieth century. They tend to be solitary by nature, watchers, thinkers, contemplatives:

The man who dares to be alone can come to see that emptiness and uselessness which the collective mind fears and condemns are necessary conditions for encounter with truth.

Thomas

Merton

Rain and Rhinoceros

It is difficult to convince the solitary to abandon his silence and his limited time and energy to adopt a disciple. As a result, the artist seeking to discover his vocation often experiences loneliness rather than solitude. For a highly creative person of faith the difficulty may become excruciating:

Do not say that Christian art is impossible. Say rather that it is difficult, doubly difficult, difficulty squared, because it is difficult to be an artist and difficult to be a Christian, and because the whole difficulty is not merely the sum but the product of these two difficulties multiplied by one another, for it is a question of reconciling two absolutes.

Jacques Maritain

Art and Scholasticism

Maritain paints a difficult portrait indeed! If we are not to make it an impossible one we must unbury the latent call to ministry and prophecy within the vocation. It is the proper role of the Church to nurture the charisms possible for the People of God. Yet, with one foot in a utilitarian society and one foot in the heavenly one, how is the artist to respond? Clearly, he must risk himself in a process of discovery. Second, there must be response from the community of faith; whether that response is great or small, its thrust must be toward an affirmation of the artist's spiritual identity and freedom within the Church.

Where there is no vision the people will perish (Prov 29.18). Renewal in the visual arts of the Church, is, curiously, the weakest of all, painful and sporadic. Part of the reason is that creating is a delicate process. It cannot happen in the midst of turmoil and chaos. Nor is it born in a vacuum. Blessed Fra Angelico has left us fragmentary sayings that throw light on the matter:

Art demands

tranquility.

and equally powerful:

To paint the things of Christ

one must live with Christ.

Every recent pope has spoken about the need for renewal of the arts in the Church. Paul VI, a man who enjoyed intimate friendship with artists and was a great lover of art, especially understood the difficulties involved. Speaking in 1974 to a group of artists gathered in the Sistine Chapel, he said:

Forgive us for having placed on you a cloak of lead. Then we abandoned you. We resorted to oleographs and works of little real or artistic value, our only justification being that we have not had the means of understanding great things, beautiful things, things worthy of being seen. We have walked along crooked pathways where art and beauty, and even worse, the worship of God have been badly served.

Paul VI was later to exhort artists to cease to be exiles waiting at the gates of the Church, to come in and find their true home, to discover their calling as prophets. He did not use the word lightly. All prophets have responded in various degrees of trepidation to their call. They understand the very human Jonah who sailed as fast as he could in the opposite direction. Yet in the boy Samuel and in the prophet Isaiah there is another kind of response. Samuel says, Speak Lord, your servant is listening. And Isaiah, despite his unclean lips, cries out Here I am, Lord, send me.

If there is something pathetic and dangerous about a self-appointed prophet, there is something more tragic in a call left unanswered for lack of courage and faith. A gift is left unopened, a dream of God extinguished. It is God's work to purify with various burning coals the unclean lips within each of us and thereby form a voice to proclaim truth. In our times this purification must necessarily lead us to what the mystics have called the desert. There is nothing piously romantic about the desert, as anyone who has experienced it can testify. It is death. And rebirth. Because the realities of this radical experience are impossible to define, the artist and mystic invariably resort to poetic language when describing it. But first, the artist rightly may begin from an intimate solidarity with humanity. He shares its longings and poverty; he is neither less nor greater than any of its members. He will be tempted to compromise with the status quo, tempted to succeed by providing entertainments. Or he may be tempted to attack the established order in order to help the poor. Our age is, after all, the age of extremes, either of an all-pervasive conformity or of rebellion. And both exist within the Church. In the status quo of materialism the artist must recognize a false god, one which numbs receptivity of spirit. Equally, he must see that rebellion does not liberate but only increases the spiral of violence.

If the artist's vision is to find expression it must be as the fruit of his own internal revolution. It is only the word of truth spoken in love which liberates, heals, and unites. This is beauty: the glory of truth and love united. A word which gives life. Where, then, does the artist's revolution take place? At what point does he become an authentic prophet within the Church? St Paul warns us that prophecy will remain imperfect; yet the prophet is to begin the journey towards vision. It begins in earnest when he decides to be a disciple, when he accepts to go forth and die. This means that he abandons forever popularity and financial reward as criteria of success. Like Moses, he removes his shoes, for, unless what he creates is rooted in reverence for mystery, he will only continue to reflect the anxieties and distractions of his times. He moves, then, step by step, out through the inner compulsions and external pressures into the poorly charted territory of God's desert. There, he will either begin to pray in earnest or flee back into the world of noise and speed. If he persists, the ever unfolding insecurities will break open his fears and hopes, exposing false motives and petty ambitions in order that they may be gradually burned away.

As he goes forward through this disturbing landscape he will confront the darkness within and undergo a process of emptying out, but only for the purpose of readying himself to receive. He must not reject this humbling process. Aquinas, in a passage about angels, speaks of the dangers of pride: The very perfection of the angels exposed them to the constant danger of the gifted, the danger of enchantment with the splendour of the gifts to the denial of the Giver. Darkness may at times seem total. The path does, in fact, lead somewhere, but first it passes through nowhere. In this desert the air is clearer, though the nights are cold and the days hold all-consuming heat. A place where deceptive sounds ring and distances and mirages melt into confusion. It is here that false securities are lost. It is here that the artist will discover miraculous glimpses of fire, signs of the country he is being led towards, still beyond his horizon. Here, he will be taught to trust in things the eye hath not seen, and will conceive the signs and promises of love to carry back to his people. It is a place of fearful beauty, and as Dostoevsky wrote, The world will be saved by beauty.

The lives of two religious artists have left us markers. Though each one's journey to the core of the creative matrix will be completely his own, in essence they are the same. Both were men of our century; both were married laymen.

|

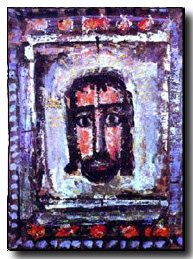

Face

of Christ Georges Rouault |

Georges

Rouault (1871-1958), the French Catholic painter, was to spend a lifetime painting

the joyful lights of Nazareth and the darkness of the human condition. As a young

man he was encouraged by his teacher, Gustave Moreau, who spoke of the poverty

which must be accepted by artists: It is necessary that their art be well-grounded

in themselves, for they will cross the desert without provisions or baggage.

Moreau once told him, Thank God that you do not have success, at least that it

is postponed as long as possible. Then it will be possible for you to reveal yourself

completely and without coercion. Years later Rouault was to write, I was only

thirty when Moreau died. Then there was a desert to cross. Knowing that I knew

nothing having certainly learned quite a bit between twenty and thirty but

I perhaps did not know the essential thing which is to strip oneself, if that

grace is accorded us. Creation for Rouault was to become a matter of life and

death. He knew that the artist, like the rich young man in the Gospel, was to

leave all. Rouault embraced his poverty and worked diligently, listening faithfully

to what he called his inner voice.

Raissa Maritain remembers him in those difficult years when he obstinately went on with his work in the midst of countless obstacles set up by poverty, a poverty that lasted many years. He was constantly torn by the needs of his wife and four children and the demands of his call. He knew how easy it would be to become a successful painter, even a successful religious painter, but understood that the price would be the loss of his vocation. Steadfastly refusing to follow the advice of even his closest associates in art and faith, he rejected the temptation to appeal to popular taste. As a result he evolved an art which is a passionate revelation of faith, not a recitation of faith. Through his prostitutes, clowns, and corrupt judges he revealed the drastic wound of sin in humanity. And through his strong and tender portrayals of Christ's life and the Cross, he made real to our eyes the redemption. By the time the accolades of the world and the Church poured in he was of advanced old age, detached, painting to the last. Creators are and ought to be solitary, he said. One is born alone . . .; solitude is the natural dwelling place of all thought.

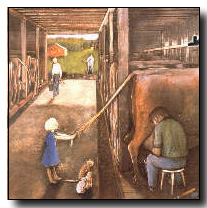

Since his death, the work of painter William Kurelek (1927-77) continues to reach far beyond the circle of Canadian art. He was a gifted and alienated youth. He suffered an emotional breakdown at an early age and spent several years in psychiatric hospitals before his conversion to Catholicism at age thirty helped bring about healing and a sense of mission to his life. Like the more placid Rouault, Kurelek was to commit everything to the service of his talent. As it matured into the fulness of vocation, various facets of his inner life emerged. Prodigiously creative, his works number in the thousands and explored an astonishing field of concern. Most widely known are his children's books and other volumes dealing with the ethnic peoples of Canada. But there is also a sizeable body of religious works which some critics dismiss as an unfortunate by-product of Kurelek's religious fanaticism. To the artist these were the heart of his work. He moralized and taught through them, protesting such things as abortion, materialism, sexual immorality, and atomic warfare. One such painting, Massacre of Highland Creek, portrays a ravine behind Scarborough Centennial Hospital. The creek is littered with overflowing buckets of aborted children, their blood sprayed on the snow. In the background rises the hospital, immaculate and banal, from which come two white-coated figures carrying yet another can of human garbage for disposal. Blood-red paint drips out of the scene over the edges of the frame.

If such works were at times incompletely formed, horrifying, or beyond the bounds of taste, they were nevertheless prophetic. One of the most eloquent is a portrayal of Christ standing on the steps of Toronto's city hall. He beckons with arms outstretched to the throngs of shoppers streaming past him, but no one sees, no one hears.

We dismiss our prophets at our own

peril, for hindsight often proves them uncannily right. The fanaticism of William

Kurelek has as its aim the protest of our destructive and selfish choices. He

probes the deep disorder in humanity in order to restore us to a vision of wholeness.

Many have found the true heart of his work in his mystical pieces. These often

autobiographical works rose from his rich inner resource of personal imagery,

where painful and joyful memories had been resolved. They portray convincingly

our humanity. Children Braving Prairie Winter Night is about terror and courage

and the eye of childhood. Another work reveals a sanctified creation as the child

Kurelek, his brothers and sisters with him, go leaping and dancing beneath the

stars. His world is rooted in the goodness of manure and sun, storm, milk, blood,

darkness, and light. It opens out through and beyond these elements into an awareness

of mystery and presence.

|

Milking

Time William Kulelek |

He died at the age of fifty, physically burnt out, but fully human, fully alive. One wonders if through his massive output of work he was trying to fill a vacuum, to be many kinds of religious artist at once, because so few others were responding to the call.

There are two major voids to be filled. There is the need to renew our culture. Though surrounded by attempts to destroy the image of God in man, the artist proclaims human dignity. In whatever style or media, he is to restore to humanity a sense of its own worth by making it conscious of the infinite. He must speak of our greatness and poverty, affirm what is healthy in society and speak honestly about what is ill. It may not be a call to evangelize with overt Christian messages. It may be to paint the beauty of earth and innocence or the horror of violence. It may be a passion, like Kurelek's, for visual story-telling, or it may be the stillness of icon and symbol. In whatever tongue of the Spirit he uses, the artist will reach beyond the community of faith to all of humanity.

There is also an urgent need in the community of faith for a holy and virile art. Here the artist's task is to seek the face of God, to search out for his people an image of Christ Jesus which is authentic. To make visible what is invisible.

How is this accomplished? The artist has no superhuman powers. Nor is he too weak to work. The artist is simply one who is called to see. Maritain says that he must become a saint.

A unity of vision, he writes, comes to perfection only as the final victory of a steady struggle inside the artist's soul, which has to pass through trials and `dark nights' comparable, in the line of creativity of the spirit, to those suffered by mystics in their striving toward God. For the Christian artist the struggle is one and the same: to remain faithful when there is no response, when no one can hear, none can see. This is the call of the prophet as well.

Suffering shall accompany him to the end. It is the mystery of the Cross, and he must embrace it without reserve, that mystery which is most neglected. In a society which believes every difficulty must be eradicated by a pill or toy, there is a tendency to sidestep the Cross. Christian artists are not infrequently accused of a lack of Christian joy. The popular modern emblems of faith are the rainbow and the much-abused butterfly. Yet they are losing their symbolic power because they have been used exhaustively to express a false joy, that of resurrection without crucifixion. It is not the intent of these reflections to present so dismal a picture of Christian art that those considering the vocation will turn sadly away, like the rich young man. It is to attempt a rough geography of the passage from Mount Horeb's burning bush down through the desert towards the promised land. The artist will wander, perhaps, like Moses, but nothing of value will be lost and the wandering will be minimal if he understands the necessity of faithfulness and attention to the promptings of the Holy Spirit. He will find that though the desert is harsh it is also beautiful. There, the face of God in us is revealed and this is a fire which the darkness cannot extinguish. There can be no greater earthly joy than learning this. It is the glory of God the Word made flesh.

The incarnating of the Word must pass through the `world of action, through states of tension and choice. The artist must learn to balance the tensions within his substrata of personal experience, myth, and subconscious symbol, resolving and developing it into visual images. This is no easy task, for the material can be chaotic. He must struggle through a painful testing of the spirit to discern what is authentic as he translates this volatile life-stock into language intelligible to the soul of his people. This means that he discerns and serves their deeper needs rather than their wants, for popular taste so often mistakes prettiness for beauty and theatrical scenes for truth. Here, the artist must also attempt to reconcile both the pull of traditional imagery and the impulse to originate, to break new ground. He needs to sink his feet deep into the rich soil of tradition and to reach high for heaven. He will experience the tension between contemplation and action, though to some degree this is a false dichotomy. If the contemplative or active, artist or mother or mechanic, are creative in their essential approach to life the tensions tend to resolve themselves. There is strength in this little trinity of action-creativity-contemplation. The artist, who is above all a contemplative, must be intimately and mysteriously connected to the agony and longings of humanity, of man in the world of action. And all his acts of making must be nourished by the waters of silence.

As a liturgical artist he will need to balance the tension between mystery and hospitality, a creative and healthy tension which should be characteristic of our places of worship. So often the parish church is a safe place where we go to keep intact our middle-class vision of existence. We want to tame God, to make the sanctuary an extension of our living rooms and ourselves into spectators consumers of the liturgy. We must re-experience the church as holy ground, welcoming and warm, but sacred. A place where we are not to be confirmed in mediocrity, but led to transfiguration. This is a particularly urgent need, because in liturgy the human soul should be opened to God, and once it has been so exposed it must be fed real food. Much of what passes for liturgical art fails to nourish because its makers have not found its source within themselves. There is talent but little or no vision. Church art rarely commands respect; it is seen by the world as a gasp from a dying Christian culture. If we are offended by these opinions we must now, more than ever, seek the origins and purposes of art and bring it to fruition in the prophetic heart of the Church.

In its Constitution on Sacred Liturgy Vatican II breathed new vigour into the sleeping body of Christian art. And in the Constitution on the Church in the Modern World we are reminded of the great importance of the arts for the life of the Church. But if we are to be heartened by these documents there must be a response to their guidelines at all levels. We need to establish the recommended diocesan councils for sacred art as advisors to guide the design and decoration of our churches. The Fathers of Vatican II also focussed on the proper development of culture as a problem of special urgency. We might begin to meet this problem by giving the fine arts a proper place in our schools. If we are attempting to equip our children only to make a living, we are adapting them to a profoundly disordered world. We are neglecting a vital part of their birthright. If we continue to pay only lip service to the arts and humanities in our educational system there will be no renaissance in the thought, the culture, the spirit of our people.

There is need of small, semi-formal colleges of sacred art. These might be attached to one or two Catholic universities in this country. Such an institute could be open not only to students and graduates of fine arts faculties but to gifted people who have not had the opportunity to study formally. It could provide an environment of spiritual formation and community, opening up for a creative person the inherent possibilities of his vocation. At present the fine arts programmes of secular universities and of even a good many Catholic ones are areligious, when they are not actually anti-religious. In such places it is common for a young person to lose his faith. And his art. There is need for an environment where vision is nourished as well as studied. We might consider collective information about religious artists in Canada and internationally. This information would be disseminated to Bishops, pastors, heads of religious communities, and advisory councils on the arts to give them a broader view of what is available. Although this risks creating a catalogue mentality, it would be a step beyond the grapevine technique currently in use. The sponsorship of continuous travelling exhibitions of sacred art would go far towards helping the average parishioner encounter good art. The success of the Vatican Exhibit which toured the United States is a sign of the response usually latent within our people.

Why could there not be a statement from the Canadian Bishops similar to Environment and Art in Catholic Worship, issued by the United States Conference of Bishops in 1978? Such guidelines would help considerably at the parish level where most of the confusion reigns and where usually much more revenue is spent on carpets and potted palms than on sacred images. There are other possibilities: grants, scholarships, study loans. Financial assistance to the artist would certainly help but in itself will not redeem the situation, for above all, attitudes need to change. No renewal of sacred art in our times will come if the artist's gift, his spiritual gift, is regarded as a piece of merchandise with which to cover the empty spaces on our walls.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

O'Brien, Michael. Fire in Our Darkness. Canadian Catholic Review (November 1984): 406-414.

Republished with permission of the Canadian Catholic Review

The Author

Michael D. O'Brien is an author and painter. His books include The Father's Tale, Father Elijah: an apocalypse, A Cry of Stone, Sophia House, Theophilos, Island of the World, Winter Tales, Voyage to Alpha Centauri, A Landscape with Dragons: the Battle For Your Child's Mind, Harry Potter and the Paganization of Culture, and William Kurelek: Painter and Prophet. His paintings hang in churches, monasteries, universities, community collections and private collections around the world. Michael O'Brien is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center. Visit his web site at: studiobrien.com.

Michael D. O'Brien is an author and painter. His books include The Father's Tale, Father Elijah: an apocalypse, A Cry of Stone, Sophia House, Theophilos, Island of the World, Winter Tales, Voyage to Alpha Centauri, A Landscape with Dragons: the Battle For Your Child's Mind, Harry Potter and the Paganization of Culture, and William Kurelek: Painter and Prophet. His paintings hang in churches, monasteries, universities, community collections and private collections around the world. Michael O'Brien is on the Advisory Board of the Catholic Education Resource Center. Visit his web site at: studiobrien.com.