Deadly Satire, Saving Grace: The Faith & Work of Evelyn Waugh

- JAMES E. PERSON, JR.

The writer of some of the most deadly satire of his age, he crafted some of Western literature's premiere novels exploring the mysteries of faith and the truth of Christianity.

|

|

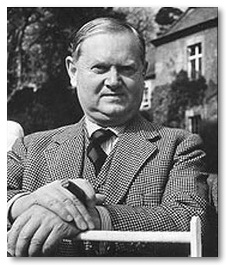

Evelyn Waugh

(1903-1966) |

As a writer, he could be deliciously cruel. In a book review, he once said that to behold one unfortunate writer's fumbling attempts to use "our rich and delicate language is to experience all the horror of seeing a Sevre vase in the hands of a chimpanzee." Of one of his friend Graham Greene's novels, he wrote that "its selection as the Book of the Month will bring it to a much larger public than can profitably read it."

As a man, he could be equally cruel. He bestowed upon family members as well as sworn enemies such nicknames as "Fat Fool" and "Hellswine." He wrote of his own children, "I can only regard children as defective adults, hate their physical ineptitude, find their jokes flat and monotonous. . . . The presence of my children affects me with deep weariness and depression." Typical was his comment on his son Auberon: "Bron is clumsy and disheveled, sly, without intellectual, aesthetic or spiritual interest."

Yet a neighbor and friend described him as "the most charming, enchanting, absolutely outstandingly lovely man I ever met." Greene wrote that he "had the rare quality of criticizing a friend, harshly, wittily and openly to his face, and behind the friend's back of expressing only his kindness and charity." His personal spiritual disciplines were rigorous, and his charity, much of it given privately, very generous.

The writer of some of the most deadly satire of his age, he crafted some of Western literature's premiere novels exploring the mysteries of faith and the truth of Christianity. William F. Buckley, Jr., considered him the twentieth century's "most finished writer of English prose" (Waugh himself suggested P. G. Wodehouse as the top candidate for that honor), and Russell Kirk declared that "in any good literary history of his time, he should loom nearly as large as T. S. Eliot."

![]()

A Stronger Faith

Born a little over 100 years ago, Evelyn Waugh stripped the follies of his time in such enduring satires as Decline and Fall (1928), A Handful of Dust (1934), Scoop (1938), and The Loved One (1948). He also wrote four novels recognized as classics of Christian humanism and the struggle for order in the soul and in society: Brideshead Revisited (1945) and a trilogy of novels published in the fifties — Men at War, Officers and Gentlemen, and Unconditional Surrender — later collected and published in one volume as Sword of Honour (1965).

In a succinct summary difficult to improve upon, the historian John Lukacs once described Waugh's view of life and faith as "a faith in God which was not only stronger than a faith in man but which included the comprehension that the two cannot be entirely separated," which included

an understanding that the knowledge of the depravity of human nature is not enough (this is what separates Waugh from Céline, with the result that Waugh's humor, unlike his mischief, is not necessarily black); a faith in a code of conduct which is noble rather than humanitarian, and self-sacrificing rather than merely brave; a belief in original sin which can be forgiving but which has surely nothing to do with evolution; a strict and narrow faith (faith, rather than trust) in heredity rather than in environment; an understanding that what people think and what they believe, even more than their material conditions, form their actions and their character.

Lukacs concluded that more people were coming to recognize his genius because "the opposites of these beliefs have become so evidently bankrupt."

Waugh loved with a fierce passion the land of his birth and its heritage of faith — not the England of the present but the old England: the England of the ancient faith, deference to the rightful authority of talent and achievement, and humble inns, the community of souls who lived close to the land — the same England celebrated by G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc before him. He hated with an equally fierce passion the modern society in which he lived, satirizing its individualism, social leveling, devil-take-the-hindmost commercialism, noise, rootlessness, and disbelief in anything that could not be experienced through the agency of the five senses.

![]()

Young Cynic

Born in 1903, Waugh was the younger of two sons born into a comfortable middle-class English family. A public-school education straight out of the darker novels of Dickens did nothing to instill a joie de vivre in the boy. (Photographs of Waugh as a young man curiously resemble photographs of the young John McEnroe on a particularly peevish day.) He came of age after World War I, in a world described by his near-contemporary, F. Scott Fitzgerald, as inhabited by "a new generation dedicated more than the last to the fear of poverty and the worship of success; grown up to find all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken."

Waugh entered fully into that dissolute world upon going to Hertford College, Oxford, in the early 1920s. He joined a circle characterized by its self-consciously airy contempt for tradition, its elevation of drink and pleasure-seeking as the highest values in life, and active homosexuality. Before leaving, after performing poorly on his exams and losing an important scholarship (he rarely studied), Waugh became a carouser and a remarkably heavy drinker.

Bored and despondent about life in general, Waugh spent the next years in a death-spiral of aimlessness and despair. He taught school, a task for which he was temperamentally unsuited, drank heavily, and eventually attempted suicide. In a much-retold story, Waugh waded out into the Atlantic to drown, first leaving behind a heroic passage from Euripides in a suicide note — only to hurry back to shore after being stung by a school of jellyfish. Quickly retrieving the now-useless note and donning dry clothes, he reluctantly decided to soldier on with life.

He entered into a brief, imprudent marriage which swiftly ended in divorce after his wife betrayed him with a friend. Amid these soul-numbing circumstances he saw his first novel published, the critically acclaimed Decline and Fall, a send-up of the trifling society of Bright Young Things of which he was so much a part — but this triumph was cold comfort. In a letter written to a friend shortly after the end of his marriage, Waugh wrote, "I did not know it was possible to be so miserable & live but I am told that this is a common experience."

God works in mysterious ways, sometimes even through the agency of jellyfish and humiliation. There were other forces at work in Waugh's life. In the short story "The Queer Feet," G. K. Chesterton's character Father Brown describes the rescue of a lost soul as the work of a faithful fisherman, who catches the fugitive creature "with an unseen hook and an invisible line which is long enough to let him wander to the ends of the world, and still to bring him back with a twitch upon the thread."

![]()

The Exile

...the brilliant Jesuit Father Martin D'Arcy, who noted that he had "never met a convert who so strongly based his assents on truth. He was a man of very strong convictions and a clear mind. He had convinced himself very unsentimentally — with only an intellectual passion, of the truth of the Catholic faith, that in it he must save his soul." |

Looking to the example and testimony of two close friends who had recently become Catholics, and having experienced firsthand a world in which the order of the soul fragmented at a touch, Waugh knew for a fact "that man is, by nature, an exile and will never be self-sufficient or complete on this earth." Ten years of having experienced the world of the Bright Young Things he had satirized in Decline and Fall "sufficed to show me that life there, or anywhere, was unintelligible or unendurable without God."

He sought the permanent, the true, and in Christianity, particularly Catholic Christianity, he found it. Weighing the claims of Catholicism, Protestantism, and agnosticism, Waugh reasoned that

if the Christian revelation was true, then the Church was the society founded by Christ and all other bodies were only good so far as they had salvaged something from the wrecks of the Great Schism and the Reformation. This proposition seemed so plain to me that it admitted of no discussion. It only remained to examine the historical and philosophic grounds for supposing the Christian revelation to be genuine. I was fortunate enough to be introduced to a brilliant and holy priest who undertook to prove this to me, and so on firm intellectual conviction but with little emotion I was admitted into the Church.

Waugh took this step in 1930, and was instructed in matters of the faith by the brilliant Jesuit Father Martin D'Arcy, who noted that he had "never met a convert who so strongly based his assents on truth. He was a man of very strong convictions and a clear mind. He had convinced himself very unsentimentally — with only an intellectual passion, of the truth of the Catholic faith, that in it he must save his soul." He converted, it should be noted, thinking that being divorced he would not be able to remarry and intending to remain alone for the rest of his life.

Writing nine years later, in Robbery Under Law, his book about his travels in Mexico (he wrote several travel books), Waugh described the vision of Christianity he held. He believed

that man is, by nature, an exile and will never be self-sufficient or complete on this earth; that his chances of happiness and virtue, here, remain more or less constant through the centuries and, generally speaking, are not much affected by the political and economic conditions in which he lives; that the balance of good and evil tends to revert to a norm.

It was a conservative vision, and the passage continues with a set of equally conservative political beliefs, among them, "inequalities of wealth and position are inevitable and . . . it is therefore meaningless to discuss the advantages of their elimination," and "the anarchic elements in society are so strong that it is a whole-time task to keep the peace."

![]()

Waugh's Presumption

Unlike many converts, who tend in later life to look nostalgically at the fervency of their first months of faith, Waugh tended to "look back aghast at the presumption with which I thought myself suitable for reception and with wonder at the trust of the priest who saw the possibility of growth in such a dry soul."

As he contemplated this, Waugh remarried (having secured an annulment of his impulsive first marriage) and continued writing, publishing several of the satires by which he is best known, including what some critics consider his masterpiece, A Handful of Dust, depicting the death-in-life of a likable protagonist, Tony Last, who drifts unresistingly with the current of his age, to his destruction. Last's life demonstrates that when triviality and spiritual inertia (the deadly sin of sloth) dominate, the grasping, malignant, and insane are the natural lords of life.

Unlike many converts, who tend in later life to look nostalgically at the fervency of their first months of faith, Waugh tended to "look back aghast at the presumption with which I thought myself suitable for reception and with wonder at the trust of the priest who saw the possibility of growth in such a dry soul." |

The realities of Waugh's new faith became clearly manifested after he began writing a life of the sixteenth-century Jesuit martyr Edmund Campion, a work published in 1935. Campion was one of the rising young men of his day, yet he gave his allegiance to the Catholic Church in total surrender, and by doing so chose his own gruesome death. "Surely it was not expected of him to give up all?" wrote Waugh rhetorically. Indeed so, for as both Campion and Waugh knew, they had pledged their lives to a faith that requires (in T. S. Eliot's words), "a condition of complete simplicity/ (Costing not less than everything)."

Though middle-aged, Waugh volunteered to serve in His Majesty's armed forces during World War II. Serving first in the Royal Marines and later in the Commandos and the Royal Horse Guards (he was a difficult man to have in one's unit), he saw intermittent active duty, and on the whole found his military service a disheartening experience of false starts, empty gestures, and self-serving strategies devised by poseurs within the uppermost ranks.

He wrote Brideshead Revisited during this time. It portrayed the effect of modernity upon English life, and the workings of "a twitch upon the thread" of faith within an old aristocratic Catholic family. It is a story of hope and redemption made possible by a faith the narrator can recount but only partly comprehend. It ends with his (and Waugh's) dismay at living in the "Age of Hooper" (the name of his crass young assistant) and his realization after praying "an ancient, newly learned form of words" in the chapel that Christ was there, represented by

a small red flame [in] a beaten-copper lamp of deplorable design, relit before the beaten-copper doors of a tabernacle; the flame which the old knights saw from their tombs, which they saw put out; that flame burns again for other soldiers, far from home, farther, in heart, than Acre or Jerusalem. It could not have been lit but for the builders and the tragedians, and there I found it this morning, burning anew among the old stones.

England, worn down by depression and war, entered the postwar world ready to hand over the reins of government to Clement Atlee's socialist Labour Party, ushering in the Age of the Dole and the Queue. This turning marked the end of the England Waugh knew and loved, and he resented it deeply.

![]()

Style & God

During the remainder of his life (he died in 1966), he struggled to hold mind and spirit together, and to write, and write as a Catholic, knowing what that commitment might do to his sales and critical reception. Writing in Life magazine in 1946, he declared,

The failure of modern novelists since and including James Joyce is one of presumption and exorbitance. . . . They try to represent the whole human mind and soul and yet omit its determining character — that of being God's creature with a defined purpose. So in my future books there will be two things to make them unpopular: a preoccupation with style and the attempt to represent man more fully, which, to me, means only one thing, man in his relation to God.

"So in my future books there will be two things to make them unpopular: a preoccupation with style and the attempt to represent man more fully, which, to me, means only one thing, man in his relation to God." |

He completed several notable works, including The Loved One, a hilarious send-up of the garish trivialization of death at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Los Angeles (1948); Helena, a fictionalized life of the Emperor Constantine's mother (1950); and a life of a friend, the Catholic convert and apologist Msgr. Ronald Knox (1959).

But his greatest postwar accomplishment as a writer was the crafting of the trilogy of novels that form the collection entitled Sword of Honour. The hero, Guy Crouchback, in many ways expresses Waugh's perceptions of a world at war and a nation in decay. In an admirable summary, Christopher Hollis writes of Crouchback:

He finds himself everywhere in the company of people with no roots, no understanding of what life is about, no sense of the dignity of its purpose. They have all adopted left-wing opinions since such opinions are now in fashion and to the advantage of one's career. Adopting such opinions, they have surrendered to a total callousness, to the appalling barbarities that are being committed in the name of these principles.

At the outset of the trilogy, Men at Arms (1952), Crouchback views with disgust the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 — the infamous alliance of Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia — and determines to take his stand for the traditional life he sees threatened: "The enemy at last was in view, huge and hateful, with all disguise cast off. It was the Modern Age in arms. Whatever the outcome there was a place for him in that battle." But by the end of the third novel, Guy, who has shed any illusions of an honorable cause in the Allied war, loses almost all desire for life, but somehow manages to survive the war, adopt the son of his faithless, doomed wife, and prepare to lead a quiet, more contented life in rural England.

Asked in an interview if there was any direct moral to Sword of Honour, Waugh replied, "Yes, I imply that there is a moral purpose, a chance of salvation, in every human life. Do you know the old Protestant hymn which goes: 'Once to every man and nation / Comes the moment to decide'? Guy is offered this chance by making himself responsible for the upbringing of Trimmer's child, to see that he is not brought up by his dissolute mother. He is essentially an unselfish character."

Waugh hoped to write a full autobiography but completed only the first volume, A Little Learning (1964), which described his life from birth to his experiences at Oxford. He died on Easter Sunday in 1966, having attended Mass and displaying to all who saw him that day a benign serenity that had escaped him for most of his life. "I have done all I could," Waugh had told an interviewer during his final years. "I have done my best."

![]()

Negative Desires

As his biographer Selina Hastings has remarked, Waugh is widely known for two things: his high accomplishment as a writer and his unpleasantness as a man. Malcolm Muggeridge, his exact contemporary, famously described him as "an antique in search of a period, a snob in search of a class; above all a mystic in search of a beatific vision."

Much has been written about Waugh's cruel tongue, his snobbery, his nostalgia for the social structure of the Victorian Age, his disdain for modernity. A strain of cruelty in Waugh ran in his family line. Hastings recounts an episode in which a wasp landed on the forehead of Waugh's paternal grandmother, and her husband (aptly nicknamed "the Brute") slowly, deliberately mashed the insect against her forehead with the head of his cane, causing the wasp to sting her.

Malcolm Muggeridge, his exact contemporary, famously described him as "an antique in search of a period, a snob in search of a class; above all a mystic in search of a beatific vision." |

Throughout his life, "the Brute's" grandson could be abrupt to the point of rudeness and did not suffer fools gladly — or, for that matter, Americans of any stripe, Jews, black Africans, the French, Italians, the working class, or many other people outside the England he had known as a boy. But he was no mere bigot, for like Jonathan Swift, he appraised individuals on their own merits but thought little of humanity in general.

In his autobiographical novel The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold (1957), he described his central character in terms that mirror his own views and temperament: "His strongest tastes were negative. He abhorred plastics, Picasso, sunbathing, and jazz — everything in fact that had happened in his own lifetime. The tiny kindling of charity which came to him through his religion sufficed only to temper his disgust and change it to boredom."

It was often the case that well-meaning people who bored Waugh found themselves treated with indifference or cut off with a sharp retort, and they mistook this for snobbish high-handedness on Waugh's part rather than a strategy he devised to guard his privacy. As his son Auberon wrote, Waugh "occupied the social position which his talents commanded, and although he punctiliously answered all letters except those from obvious lunatics or Americans, he saw no reason why his time should be spent in the company of those he had not chosen."

Waugh was undoubtedly a difficult man, but if he was ogreish on occasion, he was also tormented by the knowledge of his ogreishness, and repentant of his flaws. He wrestled with inner demons all his adult life — boredom with life, sleeplessness he fought with narcotics, heavy drinking, a recurrent late-in-life fear of losing his mind, despair at the state of things — and in the end he won through to personal peace.

Nobody knew better than he himself of his own shortcomings, and occasionally he confided this to his closest friends. Waugh wrote to the poet (and fellow convert) Edith Sitwell, "I always think of myself," adding, "I know I am awful. But how much more awful I should be without the Faith." His friend the comic novelist Nancy Mitford (not a Christian) recalled that she once asked him how he reconciled "being so horrible with being a Christian. He replied rather sadly that were he not a Christian he would be even more horrible . . . & anyway would have committed suicide years ago."

![]()

Waugh's Hunger

Waugh, noted the novelist Anthony Burgess, had a "Shakespearian hunger for order and stability." That is why his humor "is never flippant: Decline and Fall would not have maintained its freshness for nearly forty years if it had not been based on one of the big themes of our Western literature — the right of the decent man to find decency in the world." As Waugh himself said, "An artist must be a reactionary. He has to stand out against the tenor of the age and not go flopping along; he must offer some little opposition."

As Waugh himself said, "An artist must be a reactionary. He has to stand out against the tenor of the age and not go flopping along; he must offer some little opposition." |

A man who had suffered the fruit of disorder in his own life, and had seen its fruit in his world, Waugh knew the value of order and the difficulty of attaining it. Those critics who accuse him of an idolatrous worship of tradition and aristocracy, or of holding to a rigid and reactionary form of Christianity, miss the point of his belief. He recognized that a person who attacks a long-standing tradition the way a foolish gardener hacks at the ground around a young oak may chop through the roots and destroy the entire living thing, effecting great and unforeseen destruction beyond anything he imagined.

"Like the ancient philosopher Democritus, Waugh perceived that the only way to deal with this sorry world of ours is to laugh at it," wrote Kirk. Those who read his novels will find in them truth, about the world, the self, the faith, and what it is to be a man in a world that disdains faith and tradition. In melding faith, tradition, and literary craftsmanship, Waugh rode forth to battle against the armies of that age, his shield emblazoned with a mocking face, his lance fashioned at an ancient smithy and designed to pierce deeply — and in piercing, to heal.

In the story of Waugh's life there is much to learn about how that Truth can transform even the hardest case. He may have had himself in mind (at least in part) when in Helena he wrote his heroine's admonition to the Magi on behalf of those who must arrive at life's greatest truths by hard paths: "For his sake who did not reject your curious gifts, pray always for the learned, the oblique, the delicate. Let them not be quite forgotten at the Throne of God when the simple come into their kingdom."

As for his literary accomplishment, the surpassing wit and prescience remains; and history will show that Waugh's views of the last century and his view of man's relationship to God will stand up much better than many other more flattering and remunerative assessments.

![]()

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

James E. Person, Jr. "Deadly Satire, Saving Grace: The Faith & Work of Evelyn Waugh." Touchstone (June, 2005).

This article reprinted with permission from Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity.

Touchstone is a Christian journal, conservative in doctrine and eclectic in content, with editors and readers from each of the three great divisions of Christendom — Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox. The mission of the journal and its publisher, the Fellowship of St. James, is to provide a place where Christians of various backgrounds can speak with one another on the basis of shared belief and the fundamental doctrines of the faith as revealed in Holy Scripture and summarized in the ancient creeds of the Church.

The Author

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (October 28, 1903 - April 10, 1966) was an English writer, best known for such satirical and darkly humorous novels as Decline and Fall, Vile Bodies, Scoop, A Handful of Dust, and The Loved One, as well as for more serious works, such as Brideshead Revisited and the Sword of Honour trilogy, that are influenced by his own conservative and Catholic outlook. Many of Waugh's novels depict the British aristocracy and high society, which he savagely satirizes but to which he was also strongly attracted. In addition, he wrote short stories, three biographies, and the first volume of an unfinished autobiography. His travel writings and his extensive diaries and correspondence have also been published.

American literary critic Edmund Wilson pronounced Waugh "the only first-rate comic genius that has appeared in English since Bernard Shaw," while Time magazine declared that he had "developed a wickedly hilarious yet fundamentally religious assault on a century that, in his opinion, had ripped up the nourishing taproot of tradition and let wither all the dear things of the world." Waugh's works were very successful with the reading public and he was widely admired by critics as a humorist and prose stylist, but his later, more overtly religious works, such as St. Edmund Campion: Priest and Martyr, Ronald Knox, and Helena, have attracted controversy. In his notes for an unpublished review of Brideshead Revisited, George Orwell declared that Waugh was "about as good a novelist as one can be while holding untenable opinions." The American conservative commentator William F. Buckley, Jr. found in Waugh "the greatest English novelist of the century," while his liberal counterpart Gore Vidal called him "our time's first satirist." (from Wikipedia)

|

|

James E. Person, Jr., is the author of Russell Kirk: A Critical Biography of a Conservative Mind (1999) and Earl Hamner: From Walton's Mountain to Tomorrow (2005), a critical biography of novelist/screenwriter Earl Hamner.

Copyright © 2005 Touchstone