What Happened at Fatima

- JOSEPH BOTTUM

Here's a curious thought. Maybe the single most important person in the 20th century's long struggle against communism wasn't Ronald Reagan. Maybe it wasn't Karol Wojtyla or Margaret Thatcher. Maybe it wasn't anyone whose name might leap to a cold warrior's mind for the most important figure in that long, dark struggle might have been a 10-year-old girl named Lucia dos Santos.

s

|

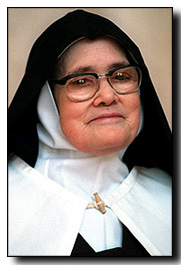

Lucia

dos Santos

(1907-2005) |

You remember her, of course. It was Lucia who went out one day in 1917 with her cousins Francisco and Jacinta Martos to tend the family's sheep and ended up having a talk about Godless Russia with the Blessed Virgin Mary near a little place in northern Portugal called Fatima.

Or do you remember her? Lucia dos Santos died on Sunday, February 13, at age 97. And for much of her life, cloistered in her Carmelite convent in Portugal, she seemed, well, what? An embarrassment, perhaps: an open invitation for mockery from nonbelievers, a creaky medievalism, a throwback to the kind of peasant superstition modern Catholics hoped would no longer be held against them.

There were certainly waves of enthusiasm about Fatima in Europe and the United States in the years following World War I. But gradually after World War II, and increasingly after the modernizing changes of Vatican II, the cult of Fatima seemed to have lived on too long, like mold in an abandoned crypt a final catacomb for the bitter and the disaffected: the orphaned throne-and-altar royalists, the bypassed ultramontanists, the rejecters of Vatican II, and all the dark, unhappy people who thought the Catholic church had abandoned them, in one way or another, for a mess of pottage at the modern world's table.

Fatima's continued existence was annoying, more or less, for educated American Catholics, who believed they had made a good-faith effort to reconcile their religion and the twentieth century. This was their grandmothers' Catholicism, which they thought they had escaped. It was an embarrassing spirituality of scapulars and rosaries, miracles and visions an outdated religion of pilgrimages and prayers for the conversion of Russia, of hushed speculation about the "third secret of Fatima" and angry disputation about whether or not the pope had actually dedicated Russia to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, as Our Lady demanded of those three little children in Portugal.

Worse, there was something not just premodern, but consciously antimodern about all of it. A day in which you can pack up your Polaroid and fly to Europe in a jumbo jet to see a visitation of the Blessed Virgin surely that's supposed to be a day in which we don't have visitations of the Blessed Virgin anymore.

And

then there was the anticommunism of Fatima. "Russia will spread its errors throughout

the world, raising up wars and persecutions of the Church. The good will be martyred,

the Holy Father will have much to suffer, and various nations will be annihilated,"

the Blessed Virgin warned in 1917. The world was going to suffer "by means of

war, hunger, and persecution," and Russia was the "instrument of chastisement."

The Catholic Church was never in much danger of becoming actively pro-Communist. As early as 1846, Pius IX condemned "that infamous doctrine of so-called communism which is absolutely contrary to the natural law itself, and if once adopted would utterly destroy the rights, property, and possessions of all men, and even society itself." In 1878, the prolific Leo XIII named communism a "fatal plague which insinuates itself into the very marrow of human society only to bring about its ruin." And in 1937, Pius XI issued an entire encyclical, Divini Redemptoris, in an effort to educate Catholics and non-Catholics alike about the dangers of "a world organization as vast as Russian communism."

Still, by the later part of the 20th century, such talk had come to seem a little dated for enlightened people or even dangerous, for those who believed the world was threatened most of all by the U.S. commitment to nuclear deterrence against the Soviet Union. When the bishops of South America met in Colombia in 1968 and defined a "preferential option for the poor," they did not intend a full embrace of Marxism. Indeed, they imagined they were developing an answer to the conditions that drew people to communism. But Latin American theologians and radicalized Catholic missionaries from the United States quickly seized upon the notion to announce a new "Theology of Liberation," born from the essential unity of Catholicism and Marxism a declaration that Communists were merely Christians in a hurry and that scientific atheism was a disposable element in Karl Marx's writing.

With the collapse of the Soviet bloc after 1989, liberation theology finally lost the fight to capture Catholic theological and intellectual circles. But there were moments in the 1970s when the liberationists looked ready to triumph, and against them stood what? A church hierarchy gradually weakening its official opposition to communism, a handful of Catholic cold warriors in the United States, a young anti-Communist archbishop in Poland who would become Pope John Paul II in 1978 and the embarrassingly dated visions of a little Portuguese nun named Sister Lucia.

When

the 93-year-old Sister Lucia met with a messenger from the pope in 2000, she repeated,

one last time, her conviction that the visions of Fatima concerned "above all

the struggle of atheistic communism against the Church and against Christians."

Those visions began in the spring of 1916, according to the children's report,

when Lucia, Francisco, and Jacinta were visited three times by an angel, who told

them he was the guardian angel of Portugal and urged them to pray and prepare

themselves.

The next spring, eight months after the angel's final visit, the Virgin Mary herself began to speak to them. Lucia had just had her tenth birthday, Francisco would turn 9 in June, and Jacinta was 7, when, on May 13, 1917, they took their sheep to a small hollow known as a Cova da Iria, the "Cove of Irene." And there, around noon, a beautiful lady appeared near an oak tree, telling them to say the Rosary every day, "to bring peace to the world and an end to the war," and promising to visit them again "on the thirteenth of each month" for the next five months.

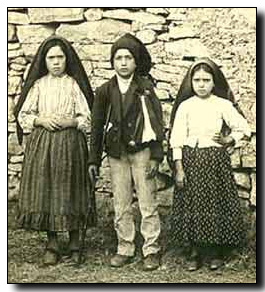

|

Lucia,

Francisco, and Jacinta in Fatima, Portugal in 1917

|

The children agreed they wouldn't tell anyone about the lady, but Jacinta couldn't keep the news to herself, and she told her parents what had happened in the cove. By all accounts, her father tended to believe her, while her mother thought she was imagining things. But they told their neighbors about the girl's story, and those neighbors told their neighbors, and those neighbors told theirs, and within a few months all of Portugal was in an uproar.

Perhaps 70 people came to the cove on June 13 to watch the children receive the second visit, in which Lucia was told that Francisco and Jacinta would not live long. Several hundred attended the third visit in July, when the children received what came to be known as the "great vision," in which the beautiful lady predicted another great war, the spread of Russia's errors, and, yes, something else the third secret the children were ordered not to tell, the prediction sealed in the Vatican's vaults, the great mystery that dominated discussions of Fatima for the next 70 years.

Portugal at the time was a republic led by a strongly anticlerical party, and the government in Lisbon apparently feared a nascent peasant revolt was brewing in the religious revival emerging from Fatima. On the morning of August 13, the local civil administrator arrested the children and hauled them away to the district headquarters in Vila Nova de Ourem where, by several accounts, he locked them in cells with "criminals" and threatened them with "boiling in oil."

It didn't have the effect for which the government had hoped. The children refused to recant, the crowds grew larger, and, under enormous public pressure, the frightened administrator returned the children, unceremoniously pushing them out of his car in front of the rectory in Fatima two days later, and driving away as fast as he could before the townspeople caught him. The delayed apparition came on Sunday, August 19, when the children were alone.

At the September apparition, Lucia, Francisco, and Jacinta were surrounded by 30,000 people, an enormous crowd for rural Portugal in 1917. And when the news spread that Mary had promised a visible sign, the witnesses swelled to 70,000 on October 13 to watch "the miracle of the sun." Amidst all the enthusiasm and mass hysteria, the ecstatic stories of the sun breaking through the clouds and dancing across the sky, there are some surprisingly sober accounts mostly by reporters from anticlerical newspapers and skeptical academics who had come to watch the crowd. "The sun's disc did not remain immobile. This was not the sparkling of a heavenly body, for it spun round on itself in a mad whirl," wrote a professor from the University of Coimbra. "Then, suddenly, one heard a clamor, a cry of anguish breaking from all the people. The sun, whirling wildly, seemed to loosen itself from the firmament and advance threateningly upon the earth as if to crush us with its huge and fiery weight. The sensation during those moments was terrible."

As the beautiful lady predicted, two of the children died young Francisco in 1919, a few months before his eleventh birthday, and Jacinta in 1920, at age 10 both carried away in the influenza epidemic that followed World War I. The Catholic Church waited until 1930 before cautiously approving prayer at Fatima as "not necessarily contrary to the faith." The cult of Our Lady of Fatima survived through the twentieth century, but seemed to be a declining devotion, particularly among educated Americans. Sermons and catechism classes as late as the 1950s were filled with references to the visions of Lucia, Francisco, and Jacinta. Yet a child who passed through Catholic education in the second half of the century would emerge with little more than a vague memory of having once or twice heard the word Fatima.

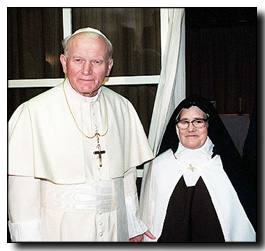

But

then, on May 13, 1991, Pope John Paul II made a visit to Portugal and drew again

to the cove the huge crowds he always attracted. And while there, he did something

curious and, at the time, inexplicable: He took the bullet with which he had been

shot 10 years before and placed it in the crown of the statue of Mary at the site

of the original apparitions.

|

It wasn't till 2000, when Francisco and Jacinta were finally beatified, that the Vatican offered an explanation and, along the way, revealed Sister Lucia's text of the third secret of Fatima, locked in the Vatican archives since 1957. The hidden part of the vision of July 13 predicted the persecution of the Church and the shooting of a pope. John Paul II had come to the conclusion that the prophecy was fulfilled by the murder attempt of May 13, 1981, when the Turkish assassin Mehmet Ali Agca shot him in St. Peter's Square.

Indeed, for the pope, it all comes together: the repeated thirteens in the dates, the vision of a gun aimed at a pope, even the anticommunism. His latest book, Memory and Identity a collection of philosophical conversations published last week in Italian and due out in English at the end of April insists upon the centrality of Fatima. The assassination attempt was "not [Agca's] initiative, someone else masterminded it, and someone else commissioned it," he declares, blaming the Soviet bloc for the shooting. It was a "last convulsion" of communism, trying vainly to hold back the tide that had turned against it. And the cause for that turn against the Soviet system? In part, at least in large part, perhaps the prayers and the attitudes inspired by the visions of Lucia, Francisco, and Jacinta at Fatima.

In many ways, John Paul II seems simultaneously far behind and far ahead of the rest of the world as though he had rediscovered the past not by retreating but by advancing, coming out at the far end of modern times, smiling and secure. He was the one who saw nothing antimodern, or even unmodern, in going to pray at the sites of ancient faith and nothing contradictory in using a jet to do it. He was the one who thought it perfectly possible that the Blessed Virgin Mary might appear in the modern age: in 1917 to a group of children in Portugal, or today, for that matter, to someone else.

And most of all, John Paul II was the one who saw that the anti-Communist visions of Fatima weren't some withdrawal into a reactionary past, but an accurate prediction of the direction modern times should take a path by which a very old form of Catholic spirituality had taught the common people to resist the Marxism their educated coreligionists had come to assume was the inevitable shape of the future. When the 97-year-old Lucia dos Santos slipped away on February 13 again, that thirteenth day she received innumerable tributes from around the world. But she was little praised for the thing she may have done best: bringing an end to the Soviet Union.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Joseph Bottum. "What Happened at Fatima." Weekly Standard 10, 23 (March 7, 2005).

Reprinted with permission from the Weekly Standard.

All rights reserved. To subscribe to the Weekly Standard click here.

The Author

Joseph Bottum is one of the nation's most widely published and influential essayists, with work in journals from the Atlantic to the Washington Post. He is a contributing editor for The Weekly Standard, holds a Ph.D. in medieval philosophy. He lives in the Black Hills of South Dakota, in the town of Hot Springs and is the author of The Second Spring: Words into Music, Music into Words, The Catholic Awakening: How Catholicism Replaced Protestant Christianity as America's National Church, and An Anxious Age: The Post-Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of America.

Joseph Bottum is one of the nation's most widely published and influential essayists, with work in journals from the Atlantic to the Washington Post. He is a contributing editor for The Weekly Standard, holds a Ph.D. in medieval philosophy. He lives in the Black Hills of South Dakota, in the town of Hot Springs and is the author of The Second Spring: Words into Music, Music into Words, The Catholic Awakening: How Catholicism Replaced Protestant Christianity as America's National Church, and An Anxious Age: The Post-Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of America.