How to beat the violent extremists

- FATHER RAYMOND J. DE SOUZA

The answer to the bad theology that gives rise to religious violence cannot be no theology. Rather, it must be good theology.

Since Islamist terror raised the curtain on the 21st century on 9/11, the refrain in this column has been the same. The answer to the bad theology that gives rise to religious violence cannot be no theology, as if jihadists should become secular liberals. The answer to bad theology must be good theology. But excellence in theology, as in other fields, cannot simply be ordered up at will. It is rare.

Since Islamist terror raised the curtain on the 21st century on 9/11, the refrain in this column has been the same. The answer to the bad theology that gives rise to religious violence cannot be no theology, as if jihadists should become secular liberals. The answer to bad theology must be good theology. But excellence in theology, as in other fields, cannot simply be ordered up at will. It is rare.

An early attempt at this response was attempted by the preeminent Christian theologian of his generation, Joseph Ratzinger/ Benedict XVI. At his famous address in Regensburg in 2006, the day after the fifth anniversary of 9/ 11, Benedict sketched out an argument that to act contrary to reason was to act contrary to God, and that violent coercion in the service of faith was contrary to reason. The lecture was greeted by riots throughout the Muslim world, but after the initial eruption the lecture was met with a respectful theological engagement by leading Islamic scholars. Yet the argument, framed by Benedict in terms of faith and reason, had limited impact because it did not explicitly address the shared biblical stories of the great Abrahamic faiths.

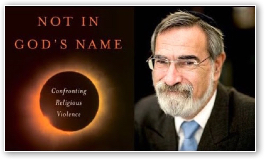

We now have such a book, excellent biblical theology, from Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, perhaps the leading Jewish scholar of his generation. Formerly chief rabbi of the Commonwealth, Rabbi Sacks is in Toronto this week, speaking about his new book, Not In God's Name: Confronting Religious Violence. It is one of the most important books since 9/11, and I am delighted to be in conversation with Rabbi Sacks about it at the Glen Gould Theatre on Tuesday night.

Sacks places the roots of religious conflict in the sibling rivalries of the scriptures sacred to Jews, Christians and Muslims. Those foundational and formational accounts deal with conflict, frequently violent conflict, not between aliens, but in the bosom of the family. "The Hebrew Bible does talk about sibling rivalry," Sacks writes. "The point could not be made more forcefully. The first religious act, Cain and Abel's offerings to God, leads directly to the first murder. God does seem to have favourites. There does seem to be a zero- sumness about the stories. It is no accident that Jews, Christians and Muslims read these stories the way they did."

That God chooses whom He chooses is clear. And it appears that when God chooses one brother, He rejects the other: Isaac chosen, Ishmael rejected; Jacob chosen, Esau rejected; Joseph chosen, his brothers rejected. The chosen therefore likewise reject the rejected, and the seeds of conflict — sometimes violent conflict — are sown. Sacks suggests an alternative.

"What if the Hebrew Bible understood, as did Freud and Girard, as did Greek and Roman myth, that sibling rivalry is the most primal form of violence?" Sacks writes. "And what if, rather than endorsing it, it set out to undermine it, subvert it, challenge it, and eventually replace it with another, quite different way of understanding our relationship with God and with the human Other? What if it turned out to be God's way of saying to us what he said to Cain: that violence in a sacred cause is not holy but an act of desecration? What if God were saying: Not in my Name?"

The strength of Sacks' exegesis is that he takes the biblical text seriously. He does not set it aside, but puts it at the centre.

The argument is detailed, but at the heart of it is something that Jews and Christians might be astonished to hear, as well as Muslims: God does not reject Ishmael — father of Muslims — in choosing Isaac — patriarch of the Jews. God chooses Isaac, but also cares for Ishmael. They join together to bury their father Abraham. The story ends in reconciliation, not contempt.

The strength of Sacks' exegesis is that he takes the biblical text seriously. He does not set it aside, but puts it at the centre. That's the only way religious arguments can be persuasive. Whether or not his argument will be persuasive will not be known for many years hence, but it has the capacity to effect major change.

In 1986, when St. John Paul II made his historic visit to the Great Synagogue of Rome, he famously referred to Jews as "our elder brothers in the faith." It was a term of affection that was massively well-received by Jews.

Yet when Benedict XVI made his own visit, he offered a correction. He observed, as Sacks does in this book, that it is usually the younger brother who usurps the position of the elder in the scriptures, and it would be better simply to emphasize the fraternity. From a Catholic point of view, the latest from Sacks could be considered an extended commentary on Benedict's insight.

Last month, Rabbi Sacks was awarded the Templeton Prize for his lifetime of scholarship and rabbinical service. It's the world leading religious prize. After reading Not In God's Name, there can be no doubt that it is well-deserved.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "How to beat the violent extremists." National Post, (Canada) March 15, 2016.

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "How to beat the violent extremists." National Post, (Canada) March 15, 2016.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post and Fr. de Souza.

The Author

Father Raymond J. de Souza is the founding editor of Convivium magazine.

Copyright © 2016 National Post