Mother Teresa's darkness

- REV. RAYMOND DE SOUZA

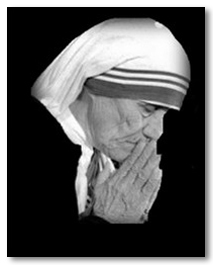

When Mother Teresa of Calcutta died 10 years ago, it was assumed that her path to official sainthood would be quick and uneventful.

Blessed Teresa of Calcutta

Blessed Teresa of Calcutta1910-1997

“Love demands sacrifice,” Mother Teresa wrote. “But if we love until it hurts, God will give us his peace and joy.”

A love that hurts? Isn’t that a contradiction? Not at all, as any parent knows. Sometimes to love is to suffer for the other. And Mother Teresa did not spare herself the suffering of the poorest of the poor whom she served.

Yet what was going on in her spiritual life was something much deeper even than that. For most of us, drawing closer to God brings feelings of peace, tranquility and joy. God grants us these consolations so that we might not tire of the spiritual life altogether. But we know from the writings of the great saints that sometimes, for those far advanced in the spiritual life, God withholds those consolations so that He is sought only for His own sake. It is what has been called by St. John of the Cross the "dark night of the soul." It does not mean that the world is bleak outside, but rather that the soul itself feels the lack of the Lord's light.

It is a form of agonizing spiritual purification, in which the soul draws very close to God. Yet God is infinite, and infinitely beyond our finite senses, so He appears as nothingness — hence the nada, nada, nada refrain of St. John of the Cross. It is not that God is nothing, but rather that infinity appears that way to the souls who see deepest. It is something like a powerful telescope; the greater its range, the more empty the heavens appear to be. It is only to those stuck on Earth that the skies seemed crowded with stars.

"God seems to hide Himself for a while,” wrote the Archbishop of Calcutta, Ferdinand Périer, to Mother Teresa in 1955. “That may be painful and if it lasts long it becomes a martyrdom. The Little Flower passed through that like the great Saint Teresa did and we may say most if not all the saints."

Mother Teresa knew something of the suffering of the derelict Jesus on the cross, apparently abandoned by the Father. She knew that Jesus, and that was her secret. Any soul who truly knows Jesus crucified, is able to recognize those crucified by the wretchedness of this world.

Archbishop Périer recognized that Mother Teresa was in the lineage of her patron saints, the "Little Flower," St. Therese of Lisieux (1873-1897), and the great mystic and doctor of the Church, St. Teresa of Avila (1515-1582). They too experienced the dark night, in which God seemed more absent than present. For Mother Teresa, that darkness was the dominant character of her spiritual life.

"If I ever become a saint, I will surely be one of 'darkness'," she wrote. "I will continually be absent from heaven — to light the light of those in darkness on Earth."

During her long life, Mother Teresa devoted herself to those living in the shadows and dark corners of life — the poor, the dying, the abandoned, the unwanted. That was the figure that captured the world’s imagination and the world’s heart. Yet she always spoke of the deeper poverty of the spirit — the poverty that comes from not knowing God, and living far from Him.

Now we know that she felt close to those souls because she too knew the absence of God. To be sure, she knew it as only those closest to God know it, as Jesus on the Cross knew it when He cried out: My God, my God, why have you abandoned me? Just as she brought the light of compassion and charity to the physically suffering, so too she thought her experiences might help her to bring the light of Christ to those in spiritual darkness.

The exclamations that mark her letters — "darkness", "I have no faith", "God is absent" — were not intended as public statements of fact, but rather the description her striving to see God beyond the comfortable images that suffice for the rest of us. Some reports got that confused, presenting Mother Teresa as something of a quasi-atheist, which is as far from the truth as possible.

Mother Teresa was above all a spiritual realist. She saw the world as it truly was, and therefore was thought by some to be a hopeless idealist. She did not see the abstract ideal of poverty reduction in some distant future; she saw the reality of a poor person, neglected and in need of love today, and so she picked him up, cleaned his wounds, and gave him a loving smile. She heard the Lord Jesus say that whatever you do to the least of these, you do to Me, and she didn’t find that some gauzy ideal. She found the lowest and least around her, and discovered in them Jesus "in the distressing disguise of the poor."

Now we have discovered that her realism was borne of daily contact with God as He really is — not in the weak analogies that we use as proxies for His presence, but in the awesome vastness of His infinity and His mercy. Mother Teresa knew something of the suffering of the derelict Jesus on the cross, apparently abandoned by the Father. She knew that Jesus, and that was her secret. Any soul who truly knows Jesus crucified, is able to recognize those crucified by the wretchedness of this world.

"The 'slum Sister' they call me," Mother Teresa wrote in her journal in 1949. "And I am glad to be just that for His love and glory."

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

Father Raymond J. de Souza, "Mother Teresa's darkness." National Post, (Canada) September 1, 2007.

Reprinted with permission of the National Post and Fr. de Souza.

The Author

Father Raymond J. de Souza is chaplain to Newman House, the Roman Catholic mission at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Convivium and a Cardus senior fellow, in addition to writing for the National Post and The Catholic Register. Father de Souza is on the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.

Father Raymond J. de Souza is chaplain to Newman House, the Roman Catholic mission at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Convivium and a Cardus senior fellow, in addition to writing for the National Post and The Catholic Register. Father de Souza is on the advisory board of the Catholic Education Resource Center.