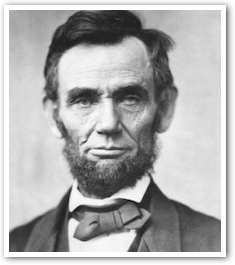

On Abortion: A Lincolnian Position

- GEORGE MCKENNA

Principled yet pragmatic, Lincoln's stand on slavery offers a basis for a new politics of civility that is at once anti-abortion and pro-choice.

|

Twenty-two years ago abortion was made an individual right by the Supreme Court. Today it is a public institution one of the most carefully cultivated institutions in America. It is protected by courts, subsidized by legislatures, performed in government-run hospitals and clinics, and promoted as a fundamental right by our State Department. As Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor observed in the 1992 Casey decision, which reaffirmed Roe v. Wade, a whole generation has grown up since 1973 in the expectation that legal abortion will be available for them if they want it.

Today our nations most prestigious civic groups, from the League of Women Voters to the American Civil Liberties Union, are committed to its protection and subsidization. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education now requires that abortion techniques be taught in all obstetrics-and-gynecology residency training programs. Influential voices in politics and the media are now demanding the assignment of U.S. marshals to protect abortion clinics against violence, and a federal law passed last year prescribes harsh criminal penalties for even nonviolent acts of civil disobedience if they are committed by demonstrators at abortion clinics. Some private organizations that administer birth-control programs and provide abortions, notably Planned Parenthood, are closely tied to government bureaucracies; Planned Parenthood receives one third of its income from federal government. Abortion today is as American as free speech, freedom of religion, or any other practice protected by our courts.

With this difference: unlike other American rights, abortion cannot be discussed in plain English. Its warmest supporters do not like to call it by its name.

Abortion is a reproductive health procedure or a termination of pregnancy. Abortion clinics are reproductive health clinics (more recently, women's clinics), and the right to obtain an abortion is reproductive freedom. Sometimes the word abortion is unavoidable, as in media accounts of the abortion controversy, but then it is almost invariably preceded by a line of nicer-sounding words: the right of a woman to choose abortion. This is still not enough to satisfy some in the abortion movement. In an op-ed piece that appeared in The New York Times shortly after a gunman killed some employees and wounded others at two Brookline, Massachusetts, abortion clinics, a counselor at one of the clinics complained that the media kept referring to her workplace as an abortion clinic. I hate that term, she declared. At the end of the piece she suggested that her abortion clinic ought to be called a place of healing and care.

The Clinton Administration, the first Administration clearly committed to abortion, seems to be trying hard to promote it without mentioning it. President Bill Clintons 1993 health-care bill would have nationalized the funding of abortion, forcing everyone to buy a standard package that included it. Yet nowhere in the bills 1,342 pages was the word abortion ever used. In various interviews both Clintons acknowledged that it was their intention to include abortion under the category of services for pregnant women. Another initiative in which the Clinton Administration participated, the draft report for last years United Nations International Conference on Population and Development, used similar language. Abortion, called pregnancy termination, was subsumed under the general category of reproductive health care, a term used frequently in the report.

Why, in a decade when public discourse about sex has become determinedly forthright, is abortion so hard to say? No one hesitates to say abortion in other contexts in referring, for example, to aborting a planes takeoff. Why not say abortion of a fetus? Why substitute a spongy expression like termination of pregnancy? And why do abortion clinics get called reproductive health clinics when their manifest purpose is to stop reproduction? Why all this strange language? What is going on here?

The answer, it seems to me, is unavoidable. Even defenders and promoters of abortion sense that there is something not quite right about the procedure. I abhor abortions, Henry Foster, President Clintons unconfirmed nominee for Surgeon General, has said. Clinton himself, who made no secret of his support for abortion during his 1992 campaign, still repeats the mantra of safe, legal, and rare abortion. Why rare? If abortion is a constitutional right, on a par with freedom of speech and freedom of religion, why does it have to be rare? The reason Clinton uses this language should be obvious. He knows he is talking to a national electorate that is deeply troubled about abortion. Shortly before last years congressional elections his wife went even further in appealing to this audience by characterizing abortions as wrong (though she added, I don't think it should be criminalized).

Sometimes even abortion lobbyists show a degree of uneasiness about what it is they are lobbying for. At the end of 1993 Kate Michelman, the head of the National Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League, was interviewed by the Philadelphia Inquirer about NARALs new emphasis on the prevention of teen pregnancies. The reporter quoted Michelman as saying, We think abortion is a bad thing. Michelman complained that she had been misquoted, whereupon she was reminded that the interview had been taped. Nevertheless, NARAL, issued a statement a few days later declaring that Michelman has never said and would never say that abortion is a bad thing. Michelman, who had reason to know better, sought only to clarify her remark in a letter to the Inquirer. It is not abortion itself that is a bad thing, she wrote. Rather, our nations high rate of abortion represents a failure of our system of sex education, contraception, and health care. But a month later Michelman herself, testifying before a House subcommittee on energy and commerce, insisted that the reporter absolutely quoted me incorrectly, and she later told a Washington Post reporter, I would never, never, never, never, never mean to say such a thing. Not until the Post reporter showed her the transcript did Michelman finally acknowledge somewhat evasively that she had said it: Im obviously guilty of saying something that led her to put that comment in there.

Whatever else Michelman's bobbing and weaving reveals, it shows how nervous abortion advocates can get when the discussion approaches the question of what abortion is. Even if we accept Michelman's amended version of her remark, which is that it is not abortion but the high rate of abortion that is a bad thing, the meaning is hardly changed. If one abortion is not a bad thing, why are many abortions bad? What is it about abortion that is so troubling?

The obvious answer is that abortion is troubling because it is a killing process. Abortion clinics may indeed be places of healing and care, as the Planned Parenthood counselor maintains, but their primary purpose is to kill human fetuses. Whether those fetuses are truly persons will continue to be debated by modern scholastics, but people keep blurting out fragments of what was long a moral consensus in this country. Once in a while even a newscaster, carefully schooled in Sprachregelungen, will slip up by reporting the murder of a woman and her unborn baby, thus implying that something more than a single homicide has taken place. But that something must not be probed or examined; the newscaster must not speak its name. Abortion has thus come to occupy an absurd, surrealistic place in the national dialogue: It cannot be ignored and it cannot be openly stated. It is the corpse at the dinner party.

![]()

Douglas and the Democrats

Only one other institution in this country has been treated so evasively, and that is the institution that was nurtured and protected by the government during the first eighty-seven years of our nations existence: the institution of slavery.

The men who drafted the Constitution included representatives from slave states who were determined to protect their states interests. Yet they were all highly vocal proponents of human liberty. How does one reconcile liberty with slavery? They did it by producing a document that referred to slavery in three different places without once mentioning it. Slaves were persons or, sometimes, other persons in contrast to free persons. The slave trade (which the Constitution prohibited Congress from banning until 1808) was referred to as the Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit. Free states were required to return fugitive slaves to their masters in the slave states, but in that clause a slave was a person held to Service or Labour and a master was the party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.

At least the founders recognized the humanity of slaves by calling them persons; but in the next generation the status of slaves, and of blacks in general, steadily declined. By the end of the 1820s slaves were reduced to a species of property to be bought and sold like other property. Thomas Jefferson, who in 1776 had tried to insert into the Declaration of Independence a denunciation of the King for keeping open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, now agonized only in private. Publicly all he could say on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration (the last year of his life) was that the progress of enlightenment had vindicated the palpable truth, that the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of God, adding vaguely, these are grounds of hope for others.

Jefferson often shied away from public controversy, but even the most flamboyant political leaders of the early nineteenth century could become suddenly circumspect when the talk turned to slavery. Andrew Jackson left office in 1837 blaming the Souths secession threats on those northerners who insisted on talking about the most delicate and exciting topics, topics upon which it is impossible that a large portion of the Union can ever speak without strong emotion. Such talk, he said, assaulted the feelings and rights of southerners and their institutions. Jackson, usually a plainspoken man, would not mar the occasion of his last presidential address by saying the words abolitionist and slavery. When slavery was discussed during the antebellum period, it was usually in language of rights the property rights of slaveholders and the sovereign rights of states. In 1850 the famous Whig senator Daniel Webster defended his support for a tough fugitive-slave law on such grounds. What right, he asked, did his fellow northerners have to endeavor to get round this Constitution, or to embarrass the free exercise of the rights secured by the Constitution to the persons whose slaves escape from them? None at all, none at all.

Webster supported the Compromise of 1850, which attempted to settle the question of slavery in the territories acquired from Mexico by admitting California as a free state and Utah and New Mexico with or without slavery as their constitution may provide at the time of their admission. This last principle was seized upon by Stephen A. Douglas, the little giant of the Democratic Party, and made the basis of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which Douglas pushed through Congress in 1854. Nullifying the Missouri Compromise of 1820, it opened the remaining territories to slavery if the people in them voted for it. Douglass rationale was popular sovereignty, a logical extension of states rights. The premise of states rights was that any institution a state wanted to have, it should have, so long as that didn't conflict with the Constitution. Since slavery not only did not conflict with the Constitution but was protected by it, Douglas said, it followed that each state had a right to do as it pleases on the subject of slavery, and the same principle should apply to the territories. Douglass appeal was not to the fiery pro-slavery minorities in the South, who insisted that slavery was morally right, but to the vast majority in the North, who simply felt uncomfortable talking about the subject. He assured them that they didnt have to that they could avoid the subject altogether by leaving it to the democratic process. Let the people decide; if they want slavery, they shall have it; if they prohibit slavery, it shall be prohibited. But what about the rights of slaves? That, Douglas said, was one of those issues that should be left to moralists and theologians. It did not belong in the political or legal realm. In speaking of their right to own slaves, he said,

I am now speaking of rights under the Constitution, and not of moral or religious rights. I do not discuss the morals of the people of Missouri, but let them settle that matter for themselves. I hold that the people of the slaveholding states are civilized men as well as ourselves, that they bear consciences as well as we, and that they are accountable to God and their posterity and not to us. It is for them to decide therefore the moral and religious right of the slavery question for themselves within their own limits.

Looking back today on Douglass words, now 137 years old, one is struck by how sophisticated and modern they seem. He ruled out of order any debate on the morality of slavery. That was a religious question. It had no place in a constitutional debate, and we had no right to judge other people in such terms. In one of his debates with Lincoln in 1858, Douglas scolded his opponent for telling the people in the slave states that their institution violated the law of God. Better for him, he said, to cheers and applause, to adopt the doctrine of judge not lest ye be judged.

The same notions and even some of the same language have found their way into the abortion debate. In Roe v. Wade, in 1973, Justice Harry Blackmun observed that philosophers and theologians have been arguing about abortion for centuries without reaching any firm conclusions about its morality. All seemingly absolute convictions about it are primarily the products of subjective factors such as ones philosophy, religious training, and attitudes toward life and family and their values. As justices, he said, he and his colleagues were required to put aside all such subjective considerations and resolve the issue by constitutional measurement free of emotion and of predilection. As the abortion debate intensified, particularly after Catholic bishops and Christian evangelicals entered the fray in the 1970s, the word religious was increasingly used by abortion defenders to characterize their opponents. They used it in exactly the same sense that Douglas used it in the slavery debate, as a synonym for subjective, personal, and thus, finally, arbitrary. In this view, religion is largely a matter of taste, and to impose ones taste upon another is not only repressive but also irrational. This seems to be the view of the philosopher Ronald Dworkin in his book Life's Dominion (1993) and in some of his subsequent writings. What the opposition to abortion boils down to, Dworkin says, is an attempt to impose a controversial view on an essentially religious issue on people who reject it.

The approach has served as useful cover for Democratic politicians seeking to reconcile their religious convictions with their party's platform and ideology. The most highly publicized use of the religious model was the famous speech given by Mario Cuomo, then the governor of New York, at the University of Notre Dame during the 1984 presidential campaign. Characterizing himself as an old-fashioned Catholic, Cuomo said that he accepted his Church's position on abortion, just as he accepted its position on birth control and divorce. But, he asked rhetorically, must I insist you do? By linking abortion with divorce and birth control, Cuomo put it in the category of Church doctrines that are meant to apply only to Catholics. Everyone agrees that it would be highly presumptuous for a Catholic politician to seek to prevent non-Catholics from practicing birth control or getting a divorce. But the pro-life argument has always been that abortion is different from birth control and divorce, because it involves a non-consenting party the unborn child. At one point in his speech Cuomo seemed to acknowledge that distinction. As Catholics, he said, my wife and I were enjoined never to use abortion to destroy the life we created, and we never have, and he added that a fetus is different from an appendix or a set of tonsils. But then, as if suddenly recognizing where this line of reasoning might lead, he said, But not everyone in our society agrees with me and Matilda. In other words, it was just a thought don't bother with it if you don't agree. De gustibus non est disputandum.

Cuomo's speech received considerable press coverage, because it was perceived as a kind of thumb in the eye of New York's Cardinal John OConnor, who had been stressing the Church's unequivocal moral condemnation of abortion. The argument, then, was newsworthy but not at all original. New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, another pro-choice Catholic, had been saying much the same thing since the mid-1970s, and by the 1980s it had become the standard argument. One hears today from the Clintons, from spokespeople for the American Civil Liberties Union, and from the philosopher Ronald Dworkin, the journalist Roger Rosenblatt, and the celebrity lawyer Alan Dershowitz, and from legions of others that opposition to abortion is essentially religious, or private, and as such has no place in the political realm. There is a patient philosophical response to this argument, which others have spelled out at some length, but it finds no purchase in a mass media that thrives on sound bites. There is also a primal scream Murder! that is always welcomed by the media as evidence of pro-life fanaticism. But is there a proper rhetorical response, a response suited to civil dialogue that combines reason with anger and urgency? I believe there is, and the model for it is Abraham Lincoln's response to Stephen Douglas.

![]()

Lincoln and the Republicans

Lincoln had virtually retired from politics by 1854, having failed to obtain a much-coveted position in the Administration of Zachary Taylor. Then came the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Stephen Douglass masterwork, which permitted the extension of slavery into the territories. Lincoln was horrified. In his view, slavery was like a cancer or a wen, as he called it. It could be eliminated only if it was first contained. If it ever metastasized, spreading into the new territories, it could never be stopped. He viewed the Kansas-Nebraska Act as a stimulant to the growth of the cancer because it invited slave-owning squatters to settle in the new territories, create electoral majorities, and establish new slave states. One of the longest and most passionate of Lincoln's speeches was his 1854 address on the act, which rehearsed many of the themes that would reappear in his debates with Douglas.

Douglas had boasted that the Kansas-Nebraska Act furthered democracy by leaving the question of whether or not to adopt slavery up to the people in the territories. Lincoln quickly homed in on the critical weakness in this self-government argument: When the white man governs himself, that is self-government; but when he governs himself and also governs another man, that is more than self-government that is despotism. It would not be despotism, of course, if slaves were not human: That is to say, inasmuch as you do not object to my taking my hog to Nebraska, therefore I must not object to you taking your slave. This, Lincoln said, is perfectly logical, if there is no difference between hogs and negroes. Lincoln kept returning to the question of the humanity of slaves, the question that Douglas ruled out of bounds as essentially religious. Everywhere, Lincoln said, even in the South, people knew that slaves were human beings. If southerners really believed that slaves were not human, why did they join in banning the international slave trade, making it a capital offense? And if dealing in human flesh was no different from dealing in hogs or cattle, why was the slave-dealer regarded with revulsion throughout the South?

You despise him utterly. You do not recognize him as a friend, or even as an honest man. Your children must not play with his; they may rollick freely with the little negroes, but not with the slave-dealers children. If you are obliged to deal with him, you try to get through the job without so much as touching him.

Peoples moral intuitions could not be repressed; they would surface in all kinds of unexpected ways: in winces and unguarded expressions, in labored euphemisms, in slips of the tongue. Lincoln was on the lookout for these, and he forced his opponents to acknowledge their significance: Repeal the Missouri Compromise repeal all compromises repeal the declaration of independence repeal all past history, you still can not repeal human nature. It will still be the abundance of mans heart, that slavery extension is wrong; and out of the abundance of his heart, his mouth will continue to speak.

Douglas tried to evade the force of these observations by insisting that he didn't care what was chosen; all he cared about was the freedom to choose. At one point, Douglas even tried to put his own theological spin on this, suggesting that God placed good and evil before man in the Garden of Eden in order to give him the right to choose. Lincoln indignantly rejected this interpretation. God did not place good and evil before man, telling him to make his choice. On the contrary, He did tell him there was one tree, of the fruit of which, he should not eat, upon pain of certain death. I should scarcely wish so strong a prohibition against slavery in Nebraska.

Lincoln's depiction of slavery as a moral cancer became the central theme of his speeches during the rest of the 1850s. It was the warning he meant to convey in his House Divided speech, in his seven debates with Douglas in 1858, and in the series of speeches that culminated in the 1860 presidential campaign. In all these he continually reminded his audience that the theme of choice without reference to the object of choice was morally empty. He would readily agree that each state ought to choose the kind of laws it wanted when it came to the protection and regulation of its commerce. Indiana might need cranberry laws; Virginia might need oyster laws. But I ask if there is any parallel between these things and this institution of slavery. Oysters and cranberries were matters of moral indifference; slavery was not.

The real issue in this controversy the one pressing upon every mind is the sentiment on the part of one class that looks upon the institution of slavery as a wrong, and of another class that does not look upon it as a wrong. The sentiment that contemplates the institution of slavery in this country as a wrong is the sentiment of the Republican party.

Lincoln has been portrayed as a moral compromiser, even an opportunist, and in some respects he was. Though he hoped that slavery would eventually be abolished within its existing borders, he had no intention of abolishing it. Although he said, in his House Divided speech in 1858, that this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free, Lincoln made it clear in that speech, and in subsequent speeches and writings, that his intention was not to abolish slavery but to arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in course of ultimate extinction... In his first inaugural address, desperate to keep the South in the Union, he even hinted that he might support a constitutional amendment to protect slavery in the existing slave states against abolition by the federal government a kind of reverse Thirteenth Amendment. The following year he countermanded an order by one of his own generals that would have emancipated slaves in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. In that same year he wrote the much-quoted letter to Horace Greeley stating that his paramount object was not to free slaves but to save the Union, and that if he could save the Union without freeing a single slave, he would do it. But when it came down to the commitment he had made in the 1850s, Lincoln was as stern as a New England minister. Slavery, he insisted, was an evil that must not be allowed to expand and he would not allow it to expand. He struggled with a variety of strategies for realizing that principle. A month after his election, Lincoln replied in this way to a correspondent who urged him to temper his opposition to slavery in the territories: On the territorial question, I am inflexible...You think slavery is right and ought to be extended; we think it is wrong and ought to be restricted.

![]()

A Lincolnian Position on Abortion

I suggested that we can find in Lincoln's anti-slavery rhetoric a coherent position that could serve as a model for pro-life politicians today. How would this rhetoric sound? Perhaps the best way to answer this is to provide a sample of what might be said by a politician devoted to a cause but no less devoted to building broad support for it. With the readers indulgence, then, I will play that politician, making the following campaign statement:

According to the Supreme Court, the right to choose abortion is legally protected. That does not change the fact that abortion is morally wrong. It violates the very first of the inalienable rights guaranteed in the Declaration of Independence the right to life. Even many who would protect and extend the right to choose abortion admit that abortion is wrong, and that killing 1.5 million unborn children a year is, in the understated words of one a bad thing. Yet, illogically, they denounce all attempts to restrain it or even to speak out against it. In this campaign I will speak out against it. I will say what is in all our hearts; that abortion is an evil that needs to be restricted and discouraged. If elected, I will not try to abolish an institution that the Supreme Court has ruled to be constitutionally protected, but I will do everything in my power to arrest its further spread and place it where the public can rest in the belief that it is becoming increasingly rare. I take very seriously the imperative, often expressed by abortion supporters, that abortion should be rare. Therefore, if I am elected, I will seek to end all public subsidies for abortion, for abortion advocacy, and for experiments on aborted children. I will support all reasonable abortion restrictions that pass muster with the Supreme Court, and I will encourage those who provide alternatives to abortion. Above all, I mean to treat it as a wrong. I will use the forum provided by my office to speak out against abortion and related practices, such as euthanasia, that violate or undermine the most fundamental of the rights enshrined in this nations founding charter.

The position on abortion I have sketched permit, restrict, discourage is unequivocally pro-life even as it is effectively pro-choice. It does not say I am personally opposed to abortion, it says abortion is evil. Yet in its own way it is pro-choice. First, it does not demand an immediate end to abortion. To extend Lincoln's oncological trope: it concludes that all those who oppose abortion can do right now is to contain the cancer, keep it from metastasizing. It thus acknowledges the present legal status of choice even as it urges Americans to choose life. Second, by supporting the quest for alternatives to abortion, it widens the range of choices available to women in crisis pregnancies. Studies of women who have had abortions show that many did not really make an informed choice but were confused and ill-informed at the time, and regretful later. If even some of those reports are true, they make a case for re-examining the range of choices actually available to women.

Would a candidate adopting this position be obliged to support only pro-life nominees to the Supreme Court? To answer this, lets consider Lincoln's reaction to Dred Scott v. Sanford, the 1857 Supreme Court ruling that Congress had no right to outlaw slavery in the territories. Lincoln condemned the decision but did not promise to reverse it by putting differently minded justices on the Court. Instead his approach was to accept the ruling as it affected the immediate parties to the suit but to deny its authority as a binding precedent for policymaking by the other branches of the federal government. If he were in Congress, he said in a speech delivered in July of 1858, shortly before his debates with Douglas, he would support legislation outlawing slavery in the territories despite the Dred Scott decision. In our analogy we need not follow Lincoln that far to see the valid core of his position. Yes, he was saying, the Supreme Court has the job of deciding cases arising under the Constitution and laws of the United States. But if its decisions are to serve as durable precedents, they must be free of obvious bias, based on accurate information, and consistent with legal public expectation: and established practice, or at least with long-standing precedent. Since Dred Scott failed all these tests, Lincoln believed that it should be reversed, and be intended to do what he could to get it reversed. But he would not try to fill the Court with new, catechized justices (a process to which he thought Douglas had been party regarding the Illinois state bench). Instead he would seek to persuade the Court of its error, hoping that it would reverse itself. Lest this seem naive, we must remember that he intended to conduct his argument before the American people. Lincoln knew that in the final analysis durable judicial rulings on major issues must be rooted in the soil of American opinion. Public sentiment, he said, is everything in this country.

With it, nothing can fail; against it, nothing can succeed. Whoever moulds public sentiment, goes deeper than he who enacts statutes, or pronounces judicial decisions. He make possible the enforcement of these, else impossible.

The lesson for pro-life leaders today is that instead of trying to fill the Supreme Court with catechized justices, a strategy almost certain to backfire, they should content themselves with modest, competent justices who are free of ideological bias, and all the while keep their eyes on the real prize: public sentiment. Dred Scott was overturned within a decade by the Civil War, but Plessy v. Ferguson the 1896 ruling validating state-imposed racial segregation darkened the nation for fifty-eight years before it was overturned in Brown v. Board of Education. Yet during that long night civil-rights advocates were not silent. In thousands of forums, from university classrooms and law-school journals to churches and political conventions, they argued their case against American-style apartheid. In the end they not only won their legal case but also forged a new moral consensus. It took time time and patience. The lesson for pro-life advocates is that they need to take the time to lay out their case. They may hope for an immediate end to abortion, and they certainly have a First Amendment right to ask for it, but their emphasis, I believe, should be on making it clear to others why they have reached the conclusions that they have reached. They need to reason with skeptics and listen more carefully to critics. They need to demand less and explain more. Whatever the outcome, that would surely contribute to the process of reasonable public discourse.

The campaign statement I presented above is my own modest contribution to that process. It seeks common ground for a civil debate on abortion. It does not aim at a quick fix; it is based on the Lincolnian premise that nothing is possible without consensus. At the same time, it suggests that some measures can be taken here and now, and with broad public support, to contain the spread of abortion.

Would either party, today, endorse such an approach? Probably not.

It is easy to see why Democrats would run from it. Since 1972 pro-choice feminists have become increasingly important players in Democratic Party councils. In 1976 abortion lobbies got the Democratic platform committee to insert a plank in the party platform opposing a constitutional amendment banning abortion, and since then they have escalated their demands to include public funding of abortion and special federal protection of abortion clinics. No Democrat with serious national ambitions would ever risk offending them. A long list of Democrats where were once pro-life Edward Kennedy, Jesse Jackson, even Al Gore and Bill Clinton turned around in the seventies and eighties as the lobbies tightened their grip on the party. In 1992 Robert Casey, the pro-life governor of Pennsylvania, a liberal on every issue except abortion, was not even permitted to speak at the Democratic National Convention.

What is more puzzling at first glance, anyway is the tepid reception the pro-life position has received over the years from centrist Republican leaders. In the present, heated atmosphere of Republican presidential politics, most Republican candidates have been wooing pro-life voters, obviously anticipating their clout in next springs primaries. But in the day-to-day management of party affairs few Republican leaders have shown much enthusiasm for the cause. Among the ten items in Newt Gingrich's Contract With America there is no reference to abortion (in fact, there is no reference to any of the social-cultural issues that the Republicans once showcased, beyond demands for tougher child pornography laws and strengthening rights of parents). The Republican national chairman, Haley Barbour, is at odds with pro-life Republicans who accuse him of trying to scuttle the party's pro-life position. The party's leading spokespeople include vocal abortion supporters like Christine Todd Whitman, the governor of New Jersey, and William Weld, the governor of Massachusetts, and its most prominent candidates in last years elections Milt Romney in Massachusetts, Michael Huffington in California, George Pataki in New York all declared themselves pro-choice.

It would be hard to find any Republican seriously seeking national office today who would say of abortion what Lincoln said of slavery: The Republican Party think it wrong we think it is a moral, a social, and a political wrong. Why? Wasn't it the Republicans who first promised to support a human-life amendment outlawing abortion? Didn't Ronald Reagan often use his bully pulpit to speak out on behalf of the unborn? Yes but that was then. In 1980 the Republicans set out to woo those who were later called Regan Democrats, and one of the means was a pro-life plank, designed to counter the plank the Democrats had put in their platform four years earlier. The wooing worked all too well. Many of the conservative Catholics and evangelical Protestants who streamed into the Republican Party in 1980 were ex-New Dealers, and they retained elements of the old faith. They may have cooled toward the welfare state, but they were not opposed to the use of government to promote social goals. Their primary goal, the outlawing of abortion, would itself involve the use of government; but even beyond that, these new social conservatives never really shared the Republicans distrust of an activist government. Republican leaders thus greeted them warily. These Democrats-turned-Republican were seen to be useful during elections but a nuisance afterward. During the Reagan years they were given considerable verbal support, which at times greatly helped the pro-life cause (as, for example, at the UN International Conference on Population in Mexico City in 1984, when Reagan officials helped push through a final report stating that abortion in no way should be promoted as a method of family planning), though it never got beyond lip service. During the Bush Administration even lip service faltered as Republican officials decided that their party's big tent needed to accommodate the pro-choice view. Read my lips, Bush said, but he was talking about no new taxes. Bush's failure to keep his tax promise was seen as a major cause of his defeat in 1992, but in the ashes of this defeat lay what Republican leaders took to be a new sign of hope: they figured they could win elections on tax-and-spend issues as long as they kept their promises; they didn't need the social issues people anymore.

The Republicans have thus returned to where they feel most comfortable. Back in the 1880s William Graham Sumner used to say that the purpose of government is to protect the property of men and the honor of women. Modern republicans would hasten to add the property of women to this meager agenda, but the philosophy is the same. It sees the common good as the sum of individual private satisfactions. Its touchstone is the autonomous individual celebrated by John Locke in Of Civil Government (1690): free, equal, and independent is the state of nature, the solitary savage enters society only to protect what is his or hers. Here is a philosophy radically at odds with pro-life premises. If a woman has an absolute, unqualified right to her property, and if her body is part of her property, it follows that she has a right to evict her tenant whenever she wants and for whatever reason she pleases. This despotic concept of individual ownership is Republican, not Democratic. If Democrats are pro-choice for political reasons, Republicans are pro-choice in their hearts. Talk radios greatest Republican cheerleader, Rush Limbaugh, has also been an outspoken pro-lifer, but even Limbaugh has been softening that part of his message lately and small wonder. Here is Limbaugh castigating the environmental movement: You know why these environmentalist wackos want you to give up your car? Ill tell you the real reason. They don't want you to have freedom of choice. There it is. Freedom of choice: the philosophical center of modern-day Republicanism.

Well, the reader asks impatiently, if Democrats are pro-choice politically and Republicans are pro-choice philosophically, whats the point of that pro-life campaign statement? Who is going to adopt it? Perhaps the good folks in some little splinter party, but who else? I answer as follows: American party politics is very tricky, at times seemingly unpredictable. Who, in the early sixties, would have dared to predict that the Democrat would become the abortion party? But there was a subtle logic at work. By 1964 it was clear that the Democrats were about to become the civil-rights party. The feminism of the sixties rode into the reform agenda on the back of civil rights (by the end of the decade sexism had entered most dictionaries as a counterpart to racism), and high on its agenda was not just the legalization but the moral legitimization of abortion. Nevertheless, it took a dozen years for the full shift to occur. I think that within the next dozen years the shift could be reversed. To explain why, I must take a long look backward, to the parties respective positions in Lincoln's time.

![]()

Pro-life Democrats

In the 1850s it was not the Republicans but the Democrats who were the champions of unbridled individualism. As heirs of Andrew Jacksons entrepreneurialism and ultimately of Jeffersons distrust of energetic government the Democrats were wary not only of national action but also of any concept of the common good that threatened individual or local autonomy. It was the Republicans, heirs of Whig nationalism and New England transcendentalism, who succeeded under Abraham Lincoln's tutelage in constructing a coherent philosophy of national reform. In The Lincoln Persuasion (1993), a brilliant, posthumously published study of Lincoln's political thought, the political scientist J. David Greenstone traced the roots of that thought to the communitarian covenant theology of seventeenth-century Puritanism. Lincoln combined this theology, with its emphasis on public duty and public purpose, with the nationalism and institutionalism of Henry Clay and other leading Whigs, arriving at a position of political humanitarianism. Lincoln's synthesis, Greenstone noted, did not deny the importance of individual development, but it did assert that the improvement of individual and society were almost inseparably joined. Combining moral commitment with political realism, Lincoln arrived at a concept of the public good that resonated deeply among northerners, especially those large segments steeped in the culture of New England. At the time of the Civil War, then, the Democratic and Republican parties were divided not only on the slavery question but also on the larger philosophical question of national responsibility. The Democrats adopted a position of economic and moral laissez-faire, while the Republicans insisted that on certain questions the nation had to do more than formulate procedural rules; it had to make moral judgments and act on them.

This philosophical alignment, persisting through the Civil War and Reconstruction, was blurred during the Gilded Age. Then, over the course of the next forty years, something surprising happened: the parties reversed positions. Populist Democrats in the 1890s weakened their party's attachment to laissez-faire, and after progressive Republicans (whose model was Lincoln) failed to take over their party in 1912, many started moving toward the Democrats. Woodrow Wilson welcomed them and so, twenty years later, did Franklin Roosevelt. By 1936 it was the Democrats who were sounding the Lincolnian themes of national purpose and government responsibility, while the Republicans had become the champions of the autonomous individual. Since then both parties have veered and tacked, sometimes partly embracing each others doctrines, but today the congressional parties stand as far apart as they were at the height of the New Deal. President Clinton may have muddied the waters with his me, too, but more moderately response to Republican entrenchment, but in Congress the programmatic differences between parties are spelled out almost daily in party-line votes reminiscent of the late 1930s. Now as then, Republican emphasize the role of government as a neutral rule maker that encourages private initiative and protects its fruits. Now as then, Democrats emphasize the role of government as a moral leader that seeks to realize public goals unrealizable in the private sphere.

If this analysis is correct, it follows that the proper philosophical home for pro-lifers right now is the liberal wing of the Democratic Party. To test this, go back to that campaign statement I sketched earlier and make one simple change: substitute the word racism for abortion. Without much editing the statement would be instantly recognizable as the speech of a liberal Democrat. Democrats know that racism, like abortion, cannot be abolished by government fiat. But they also know that it is wrong to subsidize racist teachings publicly or to tolerate racist speech in public institutions or to permit racist practices in large-scale private enterprises. Democrats also insist that government has a duty to take the lead in condemning racism and educating our youth about its dangers. In other words, the same formula grudgingly tolerate, restrict, discourage that I have applied to abortion is what liberal Democrats have been using to combat racism over the past generation. With abortion, as with racism, we are targeting a practice that is recognized as wrong (Hilary Clinton) and a bad thing (Kate Michelman). With abortion, as with racism, we are conceding the practical impossibility of outlawing the evil itself but pledging the governments best efforts to make it rare (Bill Clinton et al). When it comes to philosophical coherence, therefore, nothing prevents Democrats from adopting my abortion position. Indeed, there is very good reason to adopt it.

It is, however, politically incorrect. Any liberal Democrat taking this stance would incur the wrath of the abortion lobbies. Protests within the party would mount, funding would dry up, connections with the party leadership would be severed, and there might be a primary challenge. Because politicians do not court martyrdom, the intimidatory power of these lobbies is formidable.

But no power lasts forever, and power grounded more in bullying than in reason is particularly vulnerable in our country. Within the liberal left, from which the Democrats draw their intellectual sustenance, there is increasing dissatisfaction with the absolutist dogma of abortion rights. Nat Hentoff, a columnist in the left-liberal Village Voice, wonders why those who dwell so much on rights refuse to consider the bare possibility that unborn human beings may also have a few rights. Hentoff, who is a sort of libertarian liberal, sees a contradiction between abortion and individual rights, but the socialist writer Christopher Hitchens may actually be more in tune with the communitarian bent of post-New Deal liberalism in his critique of pro-choice philosophy. Hitchens caused an uproar among readers and staffers of The Nation in 1989 when he published an article in which he observed with approval that more and more of his colleagues were questioning whether a fetus is `only a growth in, or appendage to, the female body. While supporting abortion in some cases, he insisted that society has a vital interest in restricting it. What struck him as ironic, and totally indefensible, was the tendency of many leftists suddenly to become selfish individualists whenever the topic turned to abortion.

It is a pity that ... the majority of feminists and their allies have struck to the dead ground of Me Decade possessive individualism, an ideology that has more in common than it admits with the prehistoric right, which it claims to oppose but has in fact encouraged.

Hitchens critique of the pro-choice position comes from his socialist premises, but even some liberal critics closer to the center have adopted a similar view, The Good Society (1991), by the sociologist Robert Bellah and his associates, reads like the campaign book of a decidedly liberal Democratic politician, someone who might challenge Bill Clinton from the left in 1996. The root of what is wrong in America, it says, is our Lockean political culture, which emphasized the pursuit of individual affluence (the American dream) in a society with a most un-Lockean economy and government. When the authors get to the topic of abortion, they again see Lockeanism as the culprit; it has turned abortion into an absolute right. In place of this kind of extreme individualism they suggest we consider the practices of twenty other Western democracies.

There is respect for the value of a womans being able to choose parenthood rather than having it forced upon her, but society also has an interest in a woman's abortion decision. It is often required that she participate in counselling; she is encouraged to consider the significance of her decision, and she must offer substantial reasons why the potential life of the fetus must be sacrificed and why bearing a child would do her real harm.

Despite its use of the strange term potential life (a usage favored by Justice Blackmun) for a living fetus, Bellah's formulation expresses coherently what modern liberalism points toward but usually resists at the last minute: a responsible communitarian position on abortion. It is not the same as my campaign statement, but it is within debating distance, and setting the two statements side by side might bring together in civil debate reasonable people from both sides.

Of course, neither position would pass muster with NARAL, NOW, the ACLU, and other pro-choice absolutists. But at some point, I think, sooner rather than later, the grip of these lobbies will have to loosen. One lesson of last years congressional elections is that the Democratic Party will suffer at the polls if it is perceived by the public as the voice of entrenched minority factions. For better or worse, the Republicans articulated a philosophy in 1994, while the Democrats, by and large, believed that all they had to do was appeal to their people. The party needs to rediscover the idea of a common good, and the abortion issue may be a suitable a place as any to start. But the Democrats will first have to break free of the abortion lobbies. That will be a formidable challenge, though not an impossible one. As the political scientist Jeffrey Berry has observed, one of the most startling features of modern American politics is how quickly political alliances can shift. National politics, Berry writes, no longer works by means of subgovernment's cozy two-way relationships between particular lobbyists and politicians. Today we live in a world of issue networks, in which many lobbies vie for attention. Something like this, I believe, is starting to happen on women's issues. One of the fast-growing feminist groups in the country right now is Feminists for Life (FFL), which has offices nationwide and has recently moved its headquarters to Washington, D.C. Founded in the 1970s by former NOW members who had been expelled for their pro-life views, FFL supports almost the entire agenda of feminism except abortion rights. Citing the pro-life stands of the founders of American feminism, including Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, they view themselves as reclaiming authentic feminism. Gay-rights groups, usually allied with the abortion lobbies, now include PLAGAL, the Pro-Life Alliance of Gays and Lesbians. In issue networks, Jeffrey Berry observes, alliances can be composed of both old friends and strange bedfellows; there are no permanent allies and no permanent enemies. The new pragmatic alliances of gays and straights, religious believers and secularists, feminists and traditionalists, may soon be demanding seats at the Democratic table. It would not be surprising if they were welcomed as liberators by many Democrats who have been forced to endorse a Me Decade ideology at odds with the spirit of their party.

![]()

Pro-Choice Republicans

What about the Republicans? Where are they headed? It is hard to say. As already noted, on a range of domestic issues the party seems to have embraced a philosophy of possessive individualism that has a distinctly pro-choice ring to it, and in this respect is no longer the party of Lincoln. Lincoln's Republicanism, as Greenstone pointed out in The Lincoln Persuasion, combined a Whiggish sense of national responsibility with a New England ethic of moral perfection. Then as now, Republicans believed in capitalist enterprise and fiscal prudence but in those days they put them in the service of broader humanitarian goals. Republicans, Lincoln said, are for both the man and the dollar, but in cases of conflict, the man before the dollar. This was true for a long time in the Republican Party. Theodore Roosevelt's notion of stewardship had traced of the Lincolnian synthesis of humanitarianism and institutional responsibility; early in this century many of the Progressives came from Republican backgrounds. Even in the 1950s Eisenhower's brand of modern Republicanism faintly echoed the old tradition of active government and moral leadership. Someday, I think, it will be rediscovered. It is a noble tradition.

Right now, though, it is out of season. The Republicans are on a laissez-faire roll. The strategy of their leaders is to marginalize right-to-lifers, get their plank out of the platform, and avoid any more messy debates over social issues. They see a golden opportunity to win more recruits by appealing to yuppies and other libertarians who hate taxes and welfare but like abortion rights. What can be said to these shrewd Republican leaders? In shrewdness and willingness it would be hard to match Abraham Lincoln. Let us, then, listen to Lincoln as he warned against weakening his party's anti-slavery plank in order to win the votes of moderates. In my judgement, he wrote to an Illinois Republican official in 1859, such a step would be a serious mistake would open a gap through which more would pass out than pass in. And so today. Many Reagan Democrats came to the Republicans in the 1980s because their own party deserted them on social issues. If the Republicans do the same, many will either drift back to the Democratic Party (many of these, remember, are former New Deal Democrats, rather liberal on economic issues) or join a third party or simply drop out (many evangelicals were apolitical before Reagan came along.) For every pro-choice yuppie voter the Republicans won, they might lose two from the religious right.

In truth, however, no one can be sure about the gains and losses resulting from one position or another on abortion, and such considerations are beside my main point, which is this: It is time at last in America for the abortion issue to be addressed with candor and clarity by politicians of both major parties. There needs to be engagement on the topic. Right now, as MacIntyre calls it, can be attributed to the more extreme elements in the pro-life movement, who have stifled reasoned argument with their cries of Murder! But much of it results from the squeamishness of pro-choicers, who simply refuse to face up to what abortion is. Nervousness, guilt, even anguish, are all hidden behind abstract, Latinate phrases. Only rarely does reality intrude. That is why Christopher Hitchens caused such a howl of pain when he published his Nation article on abortion. His crack about the possessive individualism of pro-choicers undoubtedly caused discomfort, but what must have touched a raw nerve was his description of abortion itself. After sympathizing with the emotions of rank-and-file members of the pro-life movement with their genuine, impressive, unforced revulsion at the idea of a disposable fetus Hitchens added,

But anyone who has ever seen a sonogram or has spent even an hour with a textbook on embryology knows that emotions are not the deciding factor. In order to terminate a pregnancy, you have to still a heartbeat, switch off a developing brain and, whatever the method, break some bones and rupture some organs.

Here, then is the center of it all. If abortion had nothing to do with the stilling of heartbeats and brains, there would be no abortion controversy.

Suppose, now, I were to define the controversy in this manner: It is a fight between those who are horrified by the above-mentioned acts, considering them immoral, and those who are not horrified and do not consider them immoral. Unfair, most pro-choicers would say. We are also horrified. Have we not said that we abhor abortion? Have we not called it wrong? Have we not said it should be rare? All right, then, let the debate begin: How rare should it be? How can we make it rare? In what ways, if any, can public institutions be used to discourage abortion? If abortion means stilled hearts and ruptured organs, how much of that can we decently permit?

In this debate, I have made my own position clear. It is a pro-life position (though it may not please all pro-lifers), and its model is Lincoln's position on slavery from 1854 until well into the Civil War: tolerate, restrict, discourage. Like Lincoln's, its touchstone is the common good of the nation, not the sovereign self. Like Lincoln's position, it accepts the legality but not the moral legitimacy of the institution that it seeks to contain. It invites argument and negotiation: it is a gambit, not a gauntlet.

The one thing certain right now is that the abortion controversy is not going to wither away, because the anguish that fuels it keeps regenerating. Some Americans may succeed in desensitizing themselves to what is going on, as many did with slavery, but most Americans feel decidedly uncomfortable about the stilled heartbeats and brains of 1.5 million human fetuses every year. The discomfort will drive some portion of that majority to organize and protest. Some will grow old and weary, and will falter, but others will take their place. (I have seen it already: there are more and more young faces in the annual march for life.) Pro-life protests will continue, in season and out of season, with political support or without it. Abortion, a tragedy in everyones estimation, will continue to darken our prospect until we find practical ways of dealing with it in order to make it rare. But before we can even hope to do that, we have to start talking with one another honestly, in honest language.

![]()

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

This is Meaghen Gonzalez, Editor of CERC. I hope you appreciated this piece. We curate these articles especially for believers like you.

Please show your appreciation by making a $3 donation. CERC is entirely reader supported.

Acknowledgement

McKenna, George. On Abortion: A Lincolnian Position. The Atlantic Monthly, (September 1995): 51-68.

Published with permission of the author and publisher

The Author

George McKenna teaches political science at the City College of New York. His books include A Guide to the Constitution: That Delicate Balance (1984) and The Drama of Democracy (1994).

Copyright © 1995 Atlantic Monthly